Pierre Koenig

1925-2004Pierre Koenig is undoubtedly one of the most representative figures of the Modern Movement in the United States. His residences are among the most admired, not only in the Los Angeles area but of the entire architectural production between 1950 – 1970. His use of the steel framework and the clarity of the planimetric organization of his houses show us how the Modern Movement was for the architect not only a tautological model but a language still in full evolution.

It is here, in the cacophony of a city where man and car live symbiotically…..that we can find Pierre Koenig’s work.

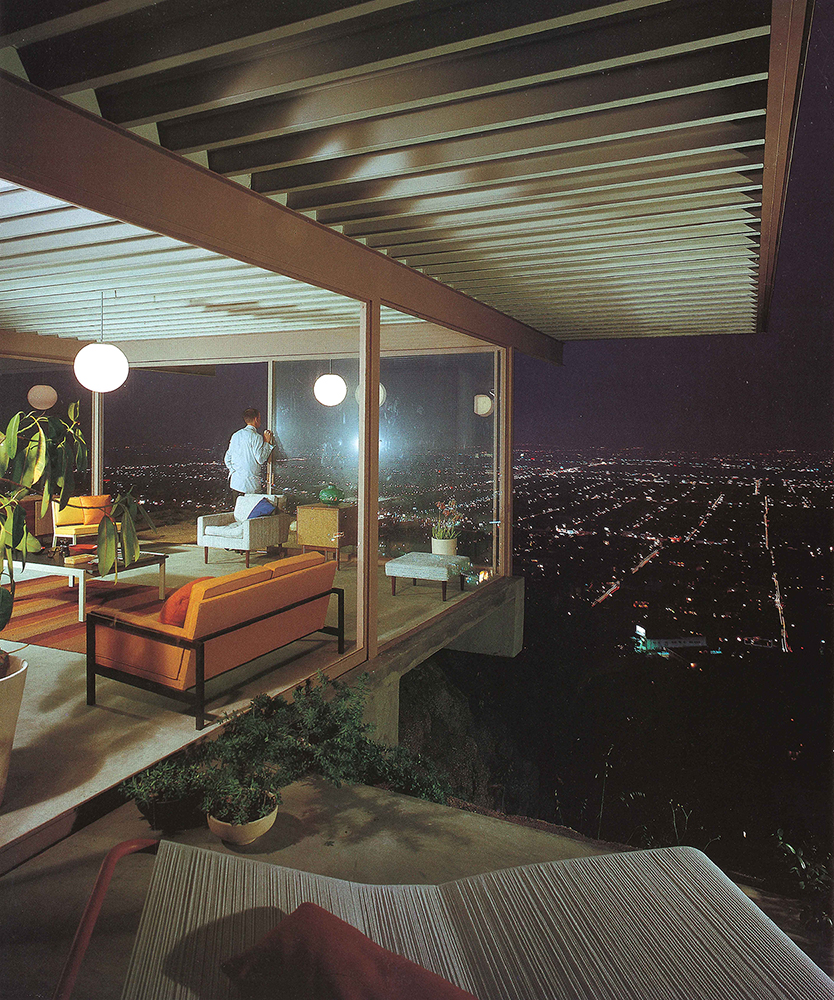

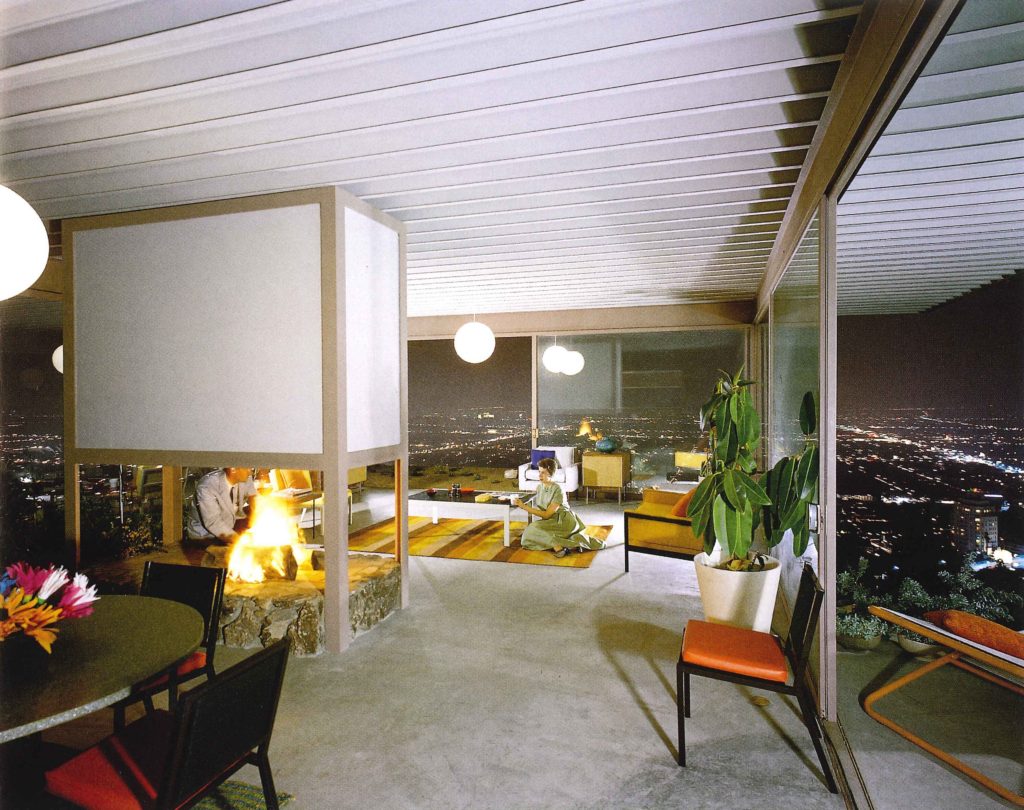

The night is dark. The sky is black, like ink. Only the reflection of the lamps on the big windows brightens the scene. The row of luminous bubbles joins the intimate residential space with this Californian castrum.

The city is down there, far below. It opens to infinity, distinguished by the lights of the boulevards and the red and white trails of cars that emphasize the frenzy of the day in their continuous, incessant motion.

Sunset Boulevard, Melrose, and then Wilshire, Miracle Mile, with their noise, anxieties, and fears are down below, far away. The city is there, with its heavy, stinking breath. Here on the hill, a modern Acropolis where everything seems to be suspended, the atmosphere is subtle. Here the air is light, there is no confusion, only silence. The smell of gasoline, of the exhausts becomes the scent of evergreen, of jasmine. The noise of the city turns into the whisper of the breeze amidst the vegetation.

Architecture floats. The windows open onto the vastity of the city landscape and are just an elusive partition. The concrete base flies, light as if it were a carpet. The projecting roof of corrugated sheet metal expands the interior space outwards.

The choice of colors and materials, the design and positioning of furniture, the clothes all give us the image of a clean space in which everything is calibrated, tuned. Despite the evident modernity of the scene, everything seems animated by a classical spirit. A composition whose creator is not only an architect but a true demiurge who seems to want to redefine with his work the Vitruvian notions of Utilitas, Firmitas, and Venustas, from which everything starts.

Architecturally speaking, Los Angeles, a city of cities, presents itself in a multifaceted way. The history of its growth recalls a range of references that in their succession describe the evolution of the city, and in a broader sense of the history of architecture. The Hispanic influences of the Churrigueresque style [1] overlap with Frank Lloyd Wright’s research, with the Deco skyscrapers of the historic downtown and the more rigorous classical modernism of the works of Rudolph Schindler [2]and Richard Neutra [3].

It is here, in the cacophony of a city where man and car live symbiotically as if they were only one thing, where architecture identifies the exceptional points of an anonymous fabric, that we can find Pierre Koenig’s work.

Born in San Francisco, Koenig grew up in the Los Angeles area where his family moved in 1939. Pierre arrived at his architectural studies after his military service in Europe during the Second World War. Thanks to the government’s program to help veterans, Koenig was admitted to the School of Architecture at USC, University of Southern California. Here, while learning the basics of the discipline, he began to confront the construction methods typical of wooden frames. Although the curriculum is focused on revitalizing the tradition of the balloon frame [4], Koenig realizes that instead steel could provide lightness and hence a new impetus to architectural expression. The opportunity to experiment with this new language presents itself when Koenig, still a student, is tasked to design and realizes his first two buildings – Koenig House (1950) and Lamel House (1953)

These two projects become a sort of design workshop which allows him to investigate the potential of a new system by adopting the industry's proposals which aim to become the new standard for construction.

His collaboration with Raphael Soriano’s studio, whose work was focused on the same investigations, reinforced Koenig’s beliefs in construction methods that adopt standardized elements.

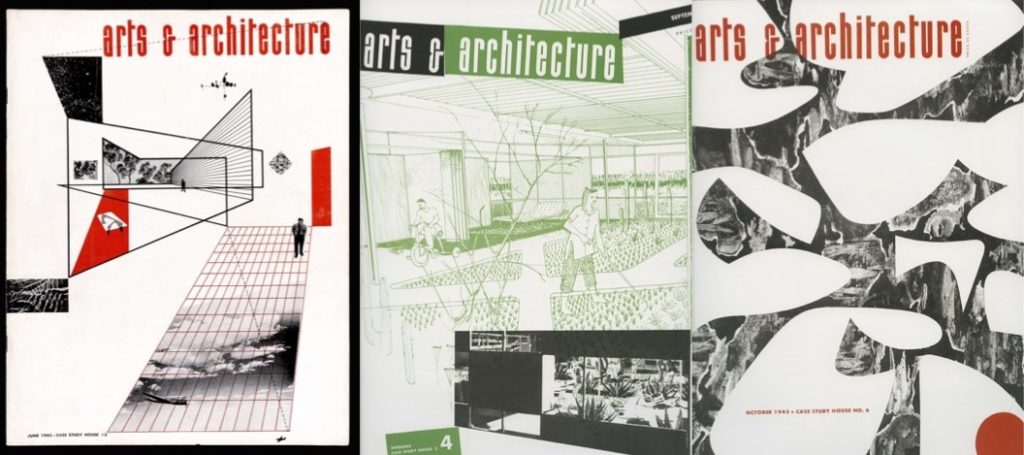

It was 1945 when John Entenza, the editor of Arts & Architecture magazine, both intercepting the aspirations of a rapidly changing society and taking advantage of the crisis in the steel industry induced by the end of WW2, opened a new era for residential architecture.

Using Arts & Architecture as a manifesto of his new program and inspired by the experiences of the Modern Movement,

Entenza invited some of the best artists, architects, and designers of the time to participate in the Case Study Houses Program (CSH 1945-1966). Studying the original principles of the golden age of Modernism, Entenza finds the ideological basis of his program in the European experiences of the period 1920 – 1930. Fascinated by the experiences of the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart (1927), he aspires to amalgamate the model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Small House with Lot of Room” of 1901 with the experiments of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion House (1930, 1945). He lays out an ambitious program that while tracing a transversal line through the history of architecture – Wright’s Usonian Houses, the Modern Movement and Fuller’s geometric experiments – proposes to create a school of thought where architecture is the focus of a broader debate that includes design, visual arts, music, and literature.

To lend gravitas to the program Entenza reached out to some of the most representative figures in the Southern California architectural community: Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen and Craig Elwood among others, who with their projects frame the program and delineate a real operational road map available to architects, clients, and manufacturers. Julius Ralph Davidson’s project in 1945 officially launches the Case Study Houses Program.

The value of the CSH as a real operational tool for practice becomes evident with the CSH # 8 and CSH # 9 residences, designed by Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen (1945 – 1949) respectively. These houses besides highlighting the versatility of a system that uses standard modular elements show an unexpected flexibility not only in responding to specific clients’ needs but also in developing an aesthetic, not to say stylistic, original character.

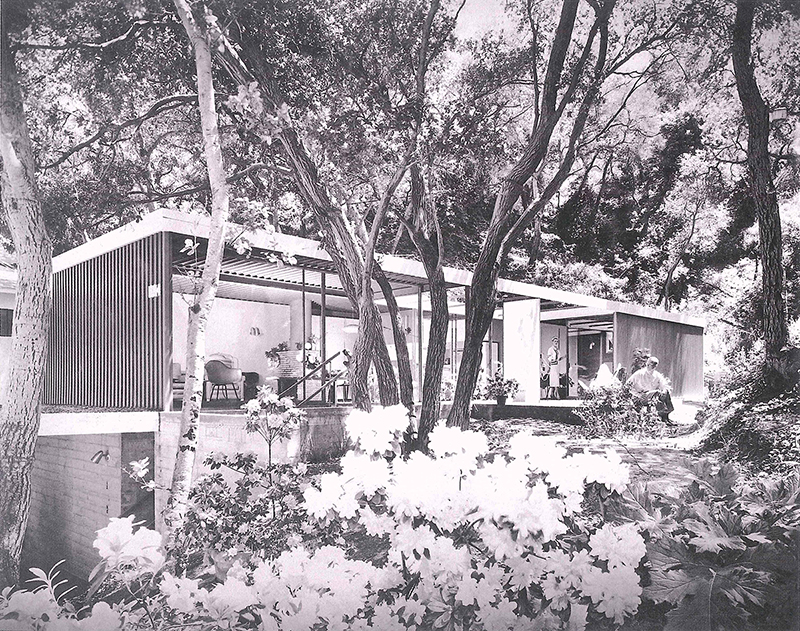

It is within this cultural framework that Koenig designs his first two houses: Koenig House (1950) and Lamel House (1953). In spite of Koenig’s still relatively recent approach to steel framework technology, these projects already show the clear intention to combine technique, aesthetics as well as cost to meet Entenza’s program considerations.

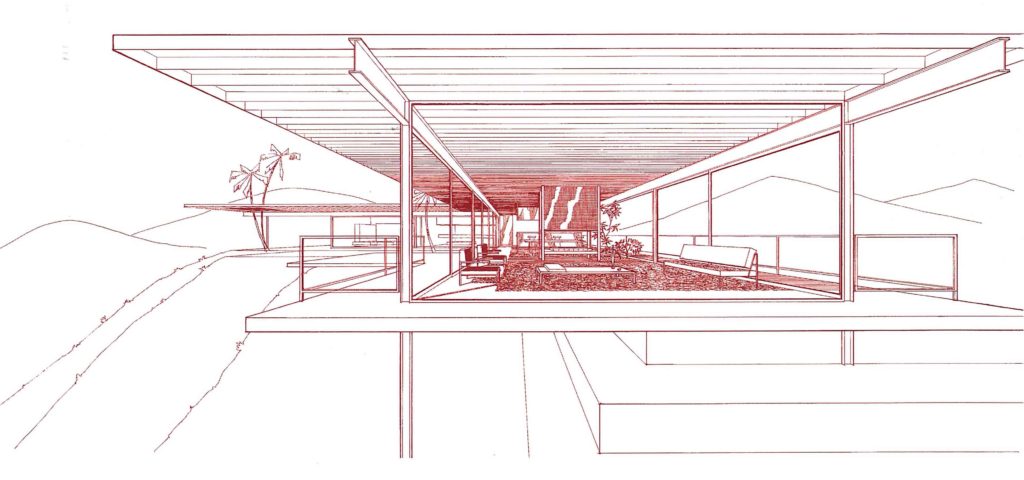

With the Bailey House (1956 – 1958, CSH # 21) the CSH program becomes the reference and focus of Koenig’s work. Both the evolution of Lamel House’s formal language and the pure geometries of the Bailey House further define the progressive distillation of structural elements as a powerful element in Koenig’s conception of architecture.

The progressively simplified layout of the structural frame and the abolition of most of the superimpositions of traditional houses point in the direction of an absolute minimalism.

“Koenig handles basic industrial materials with unusual sparseness to achieve mobile perspectives. His dispassionate examination of steel is accompanied by an inventiveness of plan and detail, a sensitivity to proportions (…)” [5]

If the way how the interior space is divided shows a disarming frankness it is in the analysis of the elevations that Koenig expresses his poetics. “Externally, the smoothness of the exposed steel frame acts as a striking visual counterpoint to the panels of profiled steel decking. The effect of the dark steel frame and lighter panels is especially striking on the east and west elevations, where the frame runs horizontally along the base and cornice.” [6]

[5] Esther McCoy, The Case Study Houses 1945 – 1962, Hennesy & Ingalls, 1978 p.53

[6] James Steele, David Jenkins Pierre Koenig Phaidon Press 1998 p. 56

When Arts and Architecture published the finished house in the February 1959 issue, the editors were prompted to suggest that: “Case Study House #21 represents a form of development of the steel house, as it represents the epitome of architectural refinements in planning and execution, in a material heretofore considered experimental. By utilizing readily available steel shapes and products in a carefully conceived manner, a finished product comparable to any other luxury home is achieved minus the excessive cost usually associated with quality and originality.” [7]

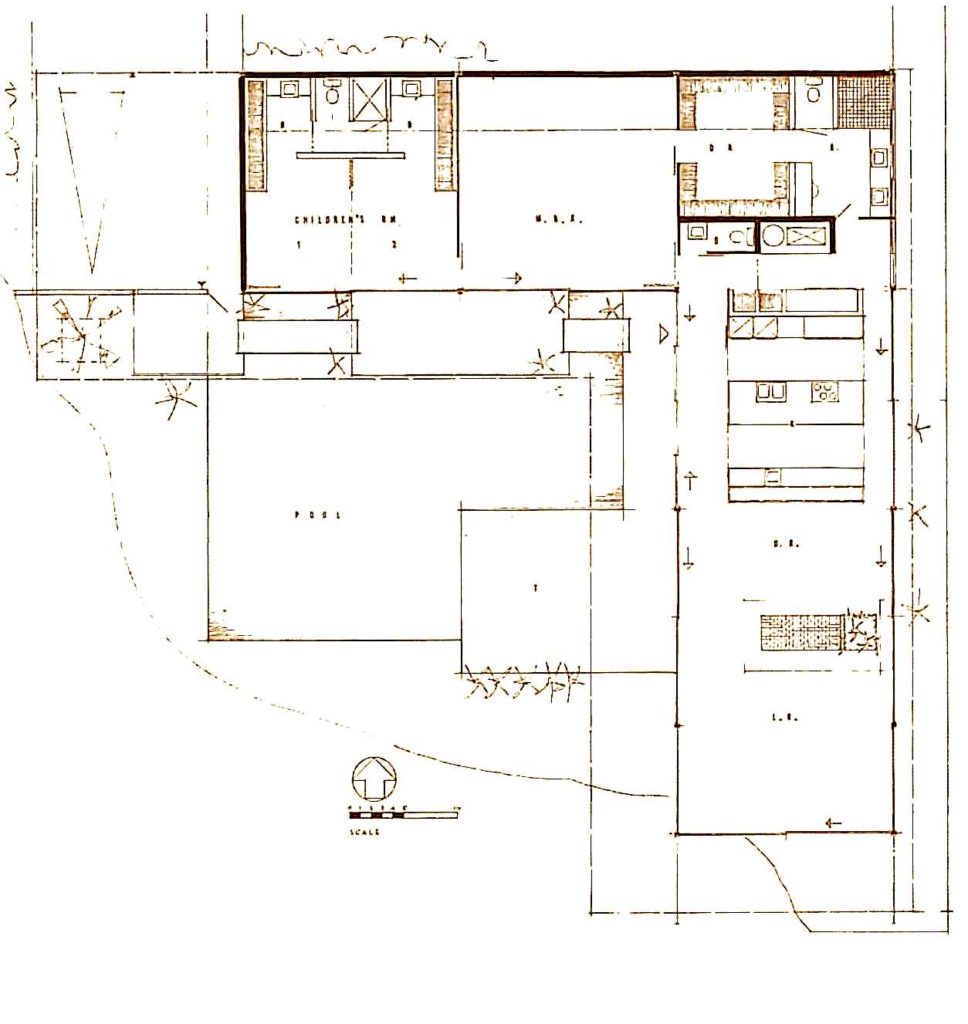

For Koenig “Style” is not the primary concern. It is neither the starting nor arrival point of his research, but the result of a pragmatic, even prosaic process, expressing a precise combination of composition and technique. In this process Koenig seems to replicate the relationship that exists between models of classical architecture and their Renaissance reinterpretations. The materials and the modular, standardized industrial elements constitute an abacus of architectural order. As in a different context it was the case with Vitruvius and Leon Battista Alberti or Palladio, Koenig’s ability to combine the steel industry’s proposals takes him to create a variety of solutions that can be used for a wide range of architectural schemes. His is an architecture characterized by the modularity of a geometric grid, perceptible both in the two dimensions of the plan and in its volumetric development.

Everything is in the right place. The neatness and completeness of the architecture recall a musical score. Observing a plan of one of Koenig’s residences is almost like reading a musical composition on a pentagram. How posts and walls are organized determines the harmony of a space and recalls the succession of musical beats. All elements of the plan are following each other, one after the next, creating with their repetition a sort of captivating melody, as in a canon.

[7] Arts & Architecture February 1959 p. 19 _ James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press 1998 p. 46-47

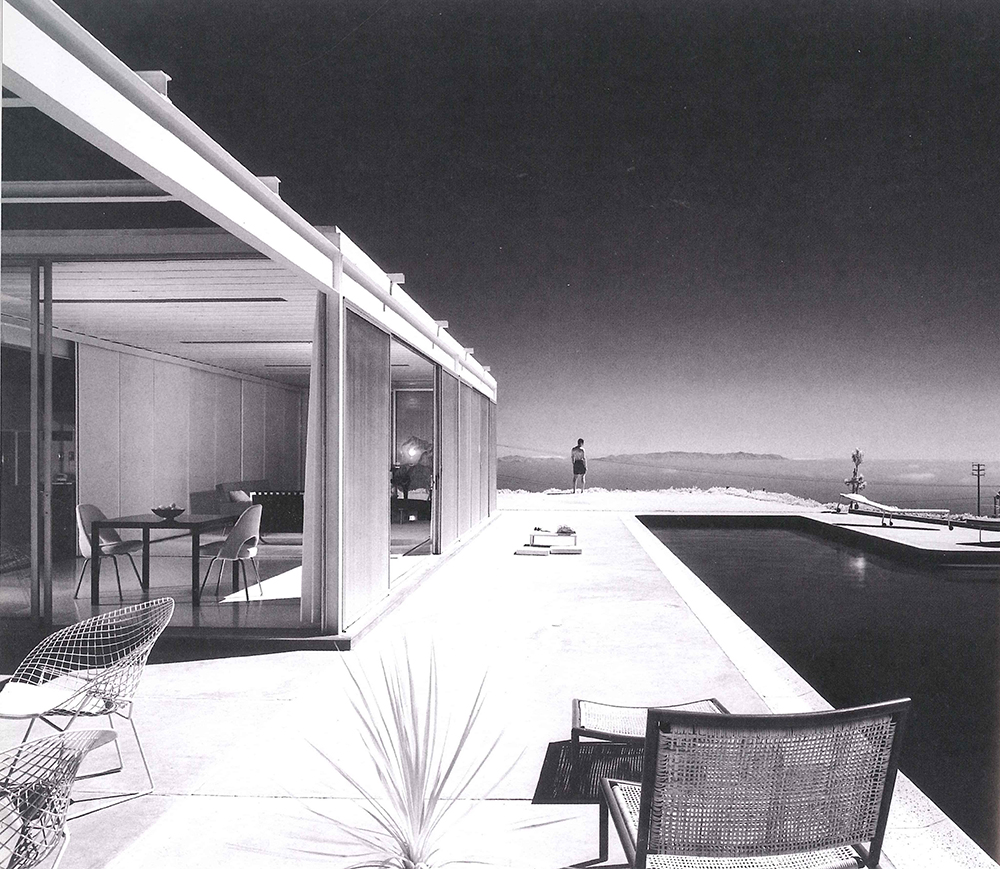

If the CSH #21 shows a highly articulated but nonetheless essential compositional language, it is in the Stahl House (CSH # 22, 1960) that Koenig demonstrates the depth of his research. Viewed as the most radical achievement of the entire Entenza program, the harmonic fusion of its generating elements – relationship with the place, planimetric organization, lightness of the structure, use of materials – make CSH #22 an example of architecture where simplicity rises to transcendence.

The house declares its nature starting from the exterior.

The modularity of the structural scheme given by the corrugated sheet metal panels reveals how even “cold” industrial material can have a strong aesthetic soul. The lightness of the structural skeleton seems to evade the laws of gravity. As Reyner Banham writes: This is, par excellence, an architecture of elegant omission that takes Mies van der Rohe’s dictum Weniger ist Mehr (Less is More) even further than the master himself had ever done. [8]

It is on the inside, on the private front, that the Stahl House shows all its expressive power. As much as the public street front is “mute” the interior is talkative. The L-shaped plan embraces the pool, the glazed panels are a diaphragm that pushes us to look beyond, towards the city, towards the ocean.

[8] Reyner Banham, Los Angeles; the Architecture of Four Ecologies, Harper & Row, 1971

The interior is in symbiosis with the surrounding place. The way space opens up with large glass panels allows us to experience the outside, the panorama, the city, without impediments.

If CSH # 21 is completely enclosed inside a box, here the cantilevered beams of the roof and the overhanging reinforced concrete beams of the base give an impetus and dynamism unknown in the other buildings. As Koenig describes: ” On the solid ground we place a swimming pool and a carport, while the house is in a certain sense floating in space.” [9]

A very successful professional decade starts for Koenig with the realization of CSH # 22. Between 1960 and 1970 one can follow the progress of his research. The relationship between geometry, structure, and use of materials – always used as in Frank Lloyd Wright’s approach for their intrinsic characteristics without mystification – becomes the matrix for the construction of space. This approach is also visible in the few non-residential projects to which Koenig dedicates himself in the years immediately following the CSH houses. In 1963 he designs the exhibition pavilion for Bethlehem Steel in iron and wood, which won the prize for best of show (1964).

[9] Neil Jackson, Koenig, Taschen 2008 p. 46

The relationship between geometry, structure, and use of materials – always used as in Frank Lloyd Wright's approach for their intrinsic characteristics without mystification – becomes the matrix for the construction of space.

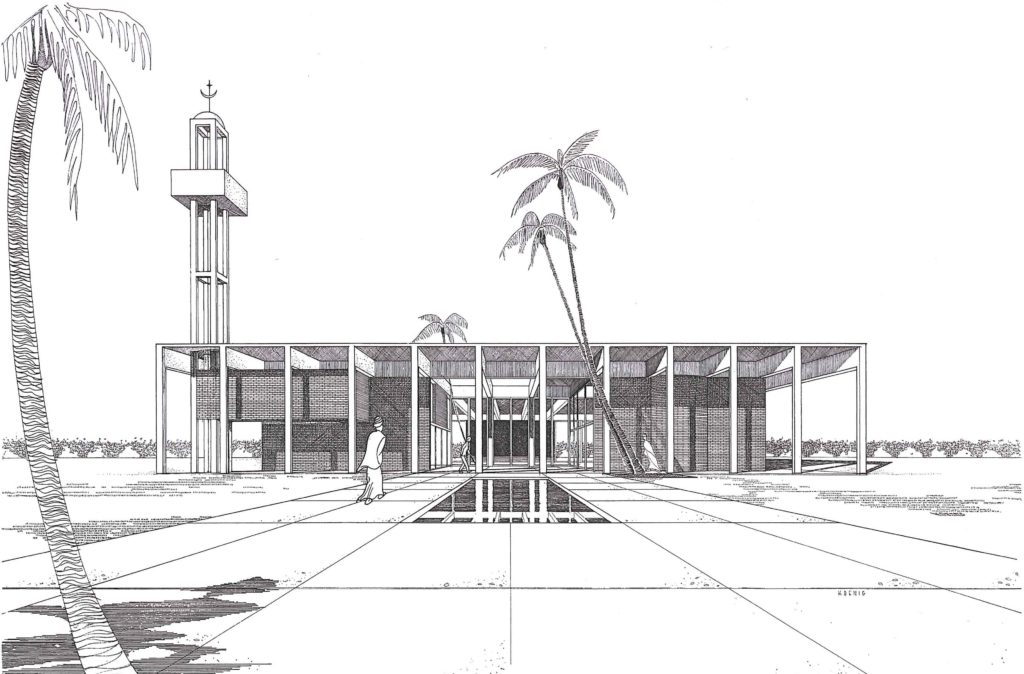

In the same year he was commissioned by the Association of Muslims of America to design the new Los Angeles mosque.

This unbuilt project again shows how the study of the materials was one of Koenig’s preferred research subjects. Here we can see the application of steel frame technology to prestressed reinforced concrete beams.

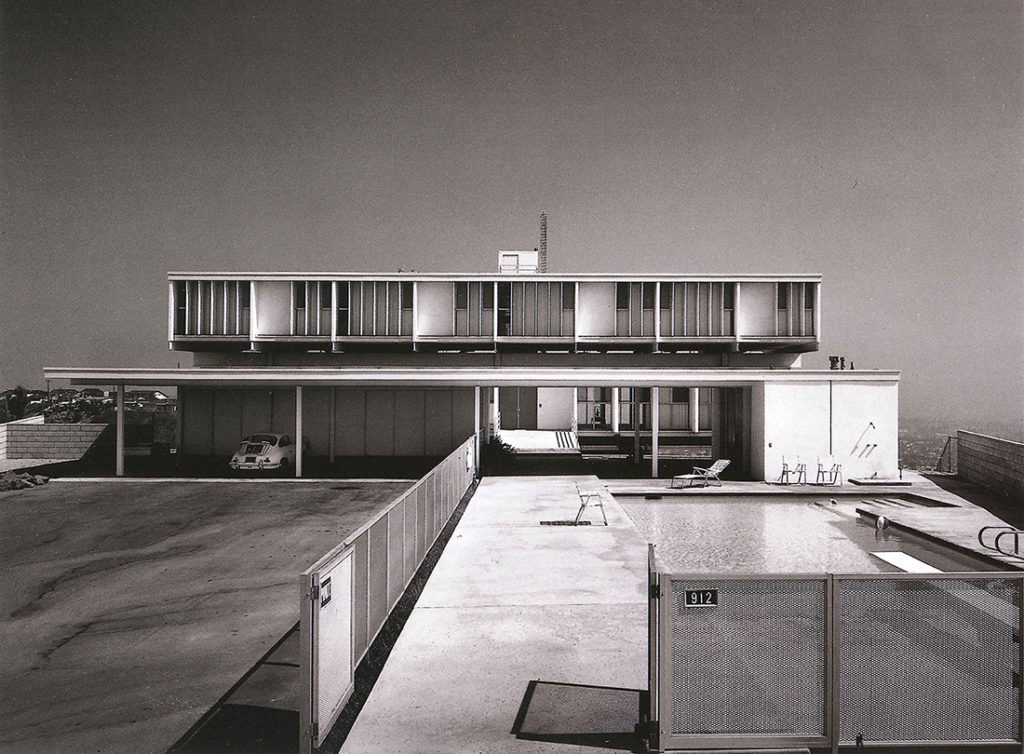

In 1962 Koenig designed the Johnson and Oberman residence. In comparison Stahl House was still, despite its “perfection”, only a next stage in his research.

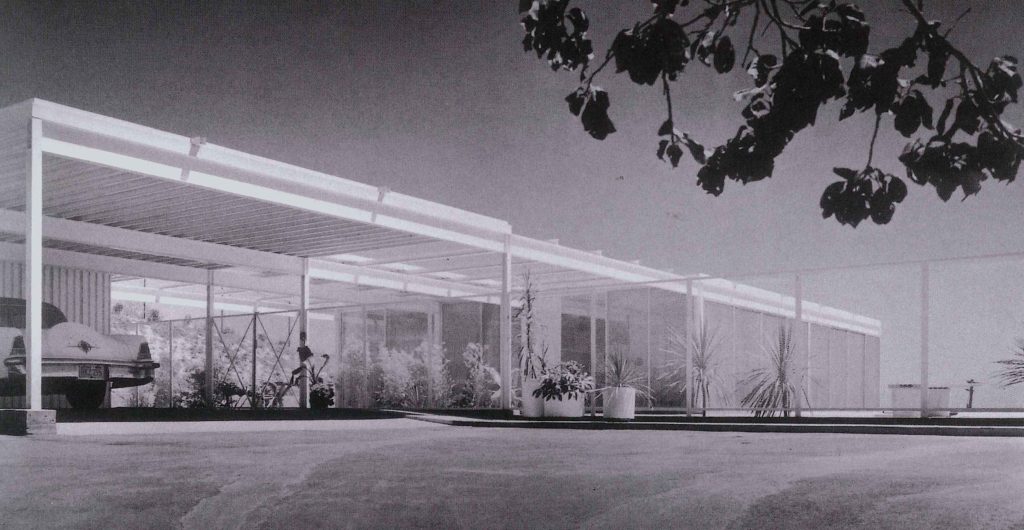

The relationship between architecture and context combined with the interest in an increasingly calibrated use of steel construction technology find in the Oberman House a new expression.

The site which is located on the promontory of the Palos Verdes hill – a natural separation between Long Beach, San Pedro Bay, and the Torrance area – resembles that of the Stahl residence in its characteristic opening towards the Pacific Ocean.

As it does on a larger scale for the city of Los Angeles, the structure becomes the real musical key to the whole project.

Avoiding the obvious trappings of symmetry, Koenig distributes the steel framework by sequencing bays of different sizes, giving the entire elevation a more articulated rhythm. The choice of putting the roof beam package lengthwise instead of the usual width orientation identifies the expressive characteristic of the project. The relationship between the truss and the slender pillars creates an aesthetic mood that recalls once again classical architecture. The beam is not only a structural element but a real frieze that furnishes the whole front with compactness and cohesion.

The choice to use white for the structure, repeated in the flooring, gives lightness to the whole building. Here too, as in the Stahl House, the role of the glazed fronts is fundamental. They allow the connection between interior and exterior, between human space and landscape, giving this building its suavity.

The Oberman residence has received numerous awards. A jury chaired by architect Edward Killingsworth included it in the group of the “36 most significant buildings built in Los Angeles since 1947” with the following motivation: “Refined example of imaginative use of industrial materials for a well-structured and detailed home”. [10]

Koenig’s language continues to evolve with the project of the residence for the Iwata family (1963).

[10] Neil Jackson, Koenig, Taschen 2008 p.60

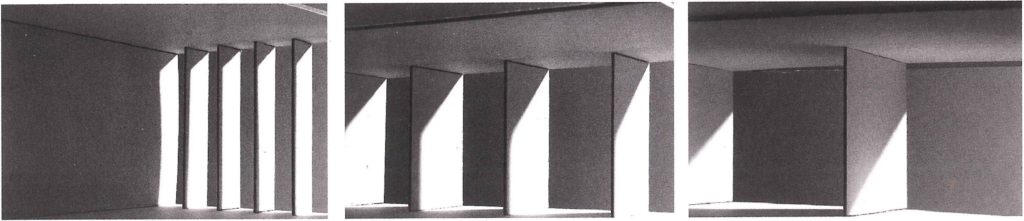

Beyond the development of the planimetric and volumetric layout – the building consists of two floors plus a basement – how the relationship with the context is generated determines the quality of the proposal. Here the dialogue with the site does not translate into an immersion of architecture into its natural surroundings, it takes a more technical/scientific approach. The study of sun exposure and direction of dominant breezes pushes Koenig to explore building on environmental characteristics as a basis for the architectural design. The need to interpret both the technical factors related to the site exposure and the construction processes defines the compositional parameters. It determines the aesthetics of the project.

The careful observation of the sun’s path throughout the day, made possible by using the Heliodon [11] allows Koenig to understand the shadow pattern inside the house with precision. At the same time, the studies of the dominant air currents’ directions provide valuable indications for the layout.

The vertical panels, forming a real brise soleil, are positioned and sized according to the orientation and exposure of the building as well as their effect on the interior. They allow the South-East elevation to let the morning sun in, and at the same time to provide shade from the midday light. Following the same principle, the panels on the North-East side, protect the interior from the summer sun at sunset.

[11] The Heliodon is a device consisting of a pivoted platform and a spotlight on a vertical track used to simulate sun and shadow orientation for any latitude and day of year for a proposed building.

While the Iwata House architectural scheme is far from the lightness of Koenig’s previous buildings, the fronts determine the aesthetic peculiarity of this residence with the repetition and subsequent superimposition of the panels.

Despite critics’ interest and recognition, Koenig’s buildings do not achieve the public success they deserve. The use of standardized industrial elements does not convince the developers of the time. They prefer to follow a mainstream product, one that is more easily understandable in its aesthetic and stylistic aspects, as Koenig himself concluded. Despite all the efforts undertaken trying to identify alternative residential models, the traditional Tract House remains the preferred typology.

For this reason, starting from the end of the 1960s Koenig’s work suffered an abrupt and long interruption. Few projects and realizations deserve mention. His research takes place in the academic field, in his courses at USC, University of Southern California, rather than in professional practice.

The rise of the Postmodernist movement takes Koenig even further away from the debate. His “method” is too pragmatic to be accepted within an architectural program based on a simulation, where the appearance is more important than its original meaning.

The projects of this period: a complex of prefabricated buildings for the Native American community of Chemehuevi (1971 -1976), the Gantert residence (1983), and his own residence (1985).

The rise of the Postmodernist movement takes Koenig even further away from the debate. His "method" is too pragmatic to be accepted within an architectural program based on a simulation, where the appearance is more important than its original meaning.

This long parenthesis is interrupted in the 90s. The completion of the Schwartz residence (1994-1996) essentially concludes this last brief segment of Koenig’s professional career. The size and conformation of the site, combined with his recent experience in the construction of his own residence, led him to favor a cube like two-story building scheme.

The need to provide the living area with a size suitable for the client’s requirements leads Koenig to raise the level of the entrance and living room. This allows him to obtain a better orientation of the building and create a carport underneath. To make the most of the landscape view and to improve the inner ventilation by exploiting local breezes, the body of the building is rotated by 30° off the road axis.

The projects for the LaFetra residence (2000) and the Tarassoly Mehran residence (2000) are his last works which are completed posthumously by James Tyler after Koenig’s death in 2004.

Looking at the entire body of Koenig’s work it is evident that his buildings have continued to teach and inspire the new generations. The value of his research goes beyond his time. Looking at the fascinating images of the 1960s, one can see how the cars, the ladies’ clothes, and the furnishings can be dated to a specific decade, while the architecture, vice versa, is thoroughly contemporary. His buildings are timeless, immortal.

The fundamental characteristic of Koenig’s work lies in its clarity of intent. His residences, unencumbered by concerns regarding style deny the concept of building envelopes as mere aesthetic manifestation in favor of a clear, honest statement of how they are made.

Their technological and aesthetic qualities are obtained through the study of proportion, geometry, size and rhythm of a structure where the weight of a building is effortlessly supported by the strength of steel.

As Norman Foster writes: ” (…) I am thinking, (…) of the heroic nighttime view of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House #22, which seems so memorably to capture the spirit of late 20th-century architecture. There, hovering almost weightlessly above the bright lights of Los Angeles, spread out like a carpet below, is an elegant, light, economical, and transparent enclosure whose apparent simplicity belies the rigorous process of investigation that made it possible. (…)” [12]

[12] James Steele, David Jenkins Pierre Koenig Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press 1998 p. 5

… an expression of lightness that tells us, in a time where the search for the impossible form and for glamour at all costs are the new rules, where trees in the sky are the new nature, that there is still so much to learn.

Selected Chronological List of Projects

1950 Koenig House, Glendale, CA

1953 Lamel House, Glendale, CA

_ Square House, La Canada, CA

_ Scott House, Tujunga, CA

1957 Burwash House, Tujunga, CA

1958 Radio Station KYCR, Blythe, CA

1959 Bailey House (CSH #21), Los Angeles, CA

1960 Stahl House (CSH #22), Los Angeles, CA

_ Seidel House, Los Angeles, CA

1961 Beidelman House, Los Angeles, CA

_ Seidel Beach House, Malibu, CA

_ St. Jean Prefab House, St. Jean, Quebec, Canada

1962 Oberman House, Palos Verdes, CA

_ Johnson House, Carmel Valley, CA

1963 Iwata House, Monterey Park, CA

1966 EEI Factory & Showroom, El Segundo, CA

1973 Franklyn Medical Bulding, Los Angeles, CA

1976 Chemehuevi Prefab tract, Havasu Lake, CA

1983 Gantert House, Los Angeles, CA

1985 Koenig House #2, Lo Angeles, CA

1989 Johnson House Addition, Carmel Valley, CA

1996 Schwartz House, Santa Monica, CA

_ Laguna House, Laguna, CA

Selected Bibliography

Banham Reyner, Los Angeles, The Architecture of Four Ecologies, harper & Brown, 1971

Ford Edward, Details of Modern Architeture, Cambridge MA, MIT Press 1996

Gattamorta Gioia, Rivalta Luca, Sogni di una metropoli, Percorsi di Architettura a Los Angeles, Firenze, Alinea, 1997

Gebhard David, Winter Robert, Los Angeles: An Architectural Guide, Layton UT, Gibbs-Smith, 1994

Goldenstein Barbara, Arts & Architecture, The Entenza Years, Cambridge MA, MIT press 1990

Jackson Neil, Koenig, Koln, Taschen 2008

Jencks Charles, Heteropolis, St Martins Pr, 1993

McCoy Esther, The Case Study Houses, 1945 – 1962, Santa Monica, CA, Hennesey & Ingalls INC, 1978

Smith A. T. Elizabeth, Blueprints for Modern Living and Legacy of the Case Study Houses, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1989

_ Case Study Houses, The Complete CSH Program 1945 – 1966, Koln, Taschen 2001

Steele James, Jenkins David, Pierre Koenig, London, Phaidon Press, 1998

Webb Michael, Modernism reborn: mid-century American houses, New York, Universe, 2001

Photo Credits

001 Stahl House, CSH 22, 1960, photo by Julius Shulman.

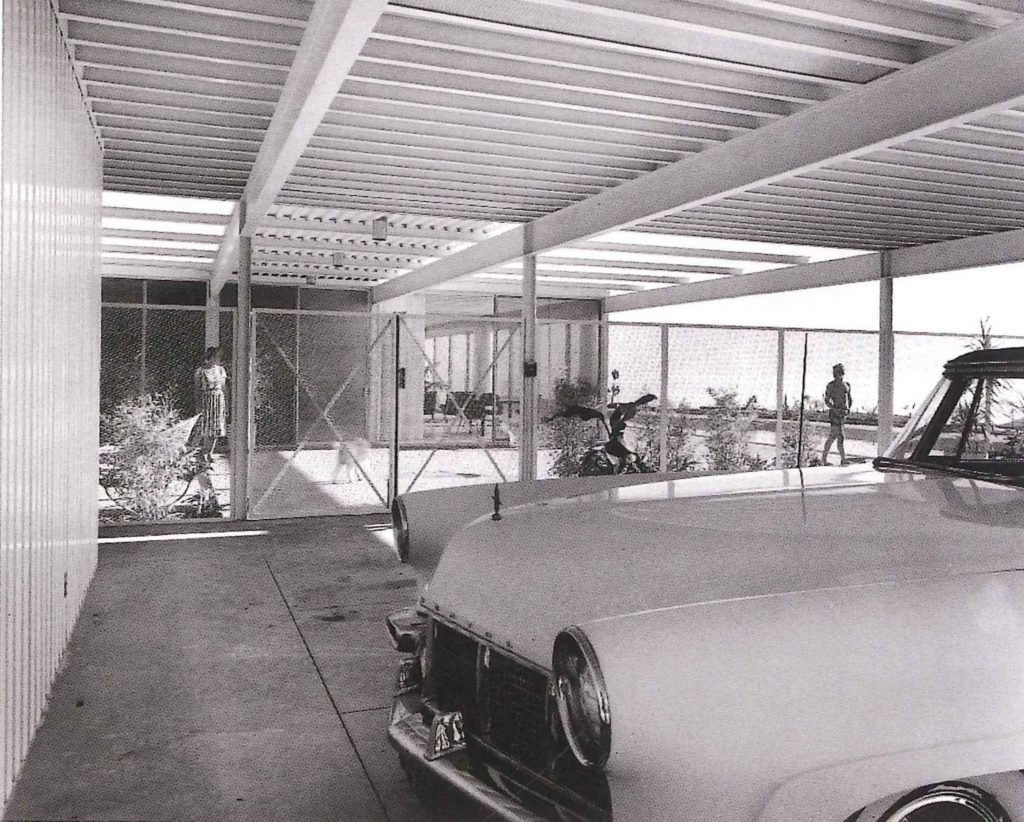

002 Lamel House 1953, photo by Julius Shulman.

003 Arts & Architecture, magazine covers

004 Julius Ralph Davidson, CSH 1, 1945-48, photo by Larry Underhill.

005 Julius Ralph Davidson, CSH 1, 1945-48, photo by Larry Underhill.

006 Charles Eames, CSH 8, 1945-49, photo from Case Study Houses, www.minniemuse.com

007 Stahl House, CSH 22, 1959-60, original photo appeared in Arts and Architecture magazine in June 1960.

008 Stahl House, CSH 22, 1959-60, original photo appeared in Arts and Architecture magazine in June 1960.

009 Stahl House, CSH 22, 1959-60, original photo appeared in Arts and Architecture magazine in June 1960.

010 Stahl House, CSH 22, 1959-60, photo by Julius Shulman.

011 Bethlehem steel exhibit pavilion, 1962, photo taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

012 Mosque, 1963, photo taken from Neil Jackson, Taschen.

013 Oberman House, 1962, photo taken from Neil Jackson, Taschen.

014 Oberman House, 1962, photo by Leland Y Lee, taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

015 Oberman House, 1962, photo by Leland Y Lee, taken from Neil Jackson, Taschen.

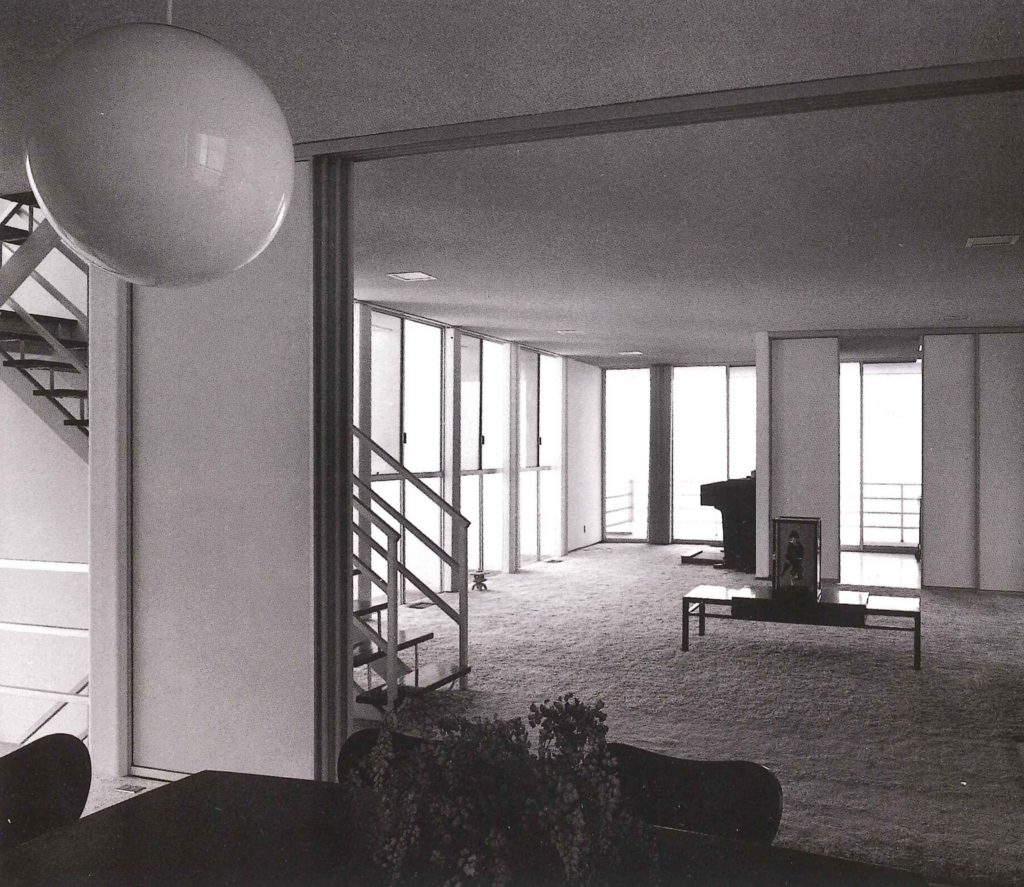

016 Iwata House, 1963, photo by Julius Shulman, taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

017 Iwata House, 1963, photo by Julius Shulman, taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

018 Iwata House, Heliodon, 1963, photo by Julius Shulman, taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

019 Iwata House, 1963, photo by Julius Shulman, taken from James Steele, David Jenkins, Pierre Koenig, Phaidon Press.

Author

Luca Rivalta graduated at the School of Architecture in Florence, where he also took his Ph.D. in architectural design. Besides his professional practice, he has carried out research and teaching activities at the School of Architecture in Florence, the Politecnico di Milano and as a visiting professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), Newark. He is the author of several essays and books about Italian and American architecture.