Margo Grant

1936 - presentMargo Grant’s life tells three stories…

Still in her twenties, Grant demonstrated both the hard skills of project-management and the soft skills of building productive, creative teams out of fractious parts.

Margo Grant’s life tells three stories: the emergence of interior design and interior architecture as a discipline distinct from interior decoration; the evolution of the status of women in architecture, a profession dominated by men, who gave women little credit for their contribution and offered them few opportunities for advancement; the journey of a Native American “white Indian” girl who started life on a hardscrabble reservation, and who, thanks to effort, poise, and persistence, became a managing director of Gensler, among the most successful architecture firms in the world.

There is also Margo Grant’s contribution to the practice of interior architecture itself: she established a legacy of design and process that is often overlooked or taken for granted. Still in her twenties, Grant demonstrated both the hard skills of project-management and the soft skills of building productive, creative teams out of fractious parts. Among the artistically inclined architects, nuts-and-bolts engineers, ego-driven clients, balky suppliers, and recalcitrant labor unionists, most were men used to getting their way. “When I think of Margo,” says Jennifer Busch, former editor-in-chief of the architecture journal, Contract, “I literally think of a boardroom full of men. Men and Margo—and she’s handling the room. She was the strong person at the table.”

It’s important to note what Margo Grant did not leave behind—there is no Margo Grant design esthetic or manifesto. Like Arthur Gensler, Grant listened to her clients to understand and address their needs and to put their concerns first. This is why her meeting Arthur Gensler was so important. There were no stand-alone stars at Gensler, Arthur liked to say. “We have a constellation of stars.”

Along the way, she broke through the glass ceiling that confronted women in architecture, clearing the way for them to advance to the top echelons in the field.

The roster of companies Grant worked with is stunning: Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, McKinsey, Bank of America, Mobil Oil, PwC, Alcoa…the list goes on, all thanks to her skill, hard work, design talent, and, especially, her ability to make friends out of clients. Along the way, she broke through the glass ceiling that confronted women in architecture, clearing the way for them to advance to the top echelons in the field.

Margolaine Grant was born on December 12, 1936, on the Blackfoot Indian Reservation in Fort Peck, Montana. Her mother was of Scottish descent on both sides, her father was Chippewa. Grant is proud of her native American heritage. In a short essay she wrote after retiring from Gensler: “I was the third and last Depression era child of Anne and Alfred Grant, Turtle Mountain Tribe, Pembina Band, Chippewa nation.” Looking back on her life, Grant noted that her “Great Plains background and good genes probably gave me strength and endurance.”

There was a lot to endure in a childhood on the Reservation. The house, built by her father, had kerosene lamps for light and no indoor plumbing or running water. “They called us ‘white Indians,’ because there was so much Scottish and French mixed in, but once you were on the reservation, you were the government’s property. When we drove into Rolla [North Dakota] for supplies, the local kids would throw rocks at us, saying, ‘Here come the Indians!”

In June 1943 the family moved to Oregon, settling in Portland, where Grant attended school and college. From the age of 15 she held part-time jobs, working variously in a ball-bearing factory and at a moving company. To earn money for college on graduating from high school, Grant found fulltime work as a junior trainee at a bank, where her secretarial skills—expert shorthand, crack typist—served her well. Initially enrolling at Portland State, she subsequently transferred to the University of Oregon, Eugene, and entered the five-year interior architecture degree program, one of the few such undergraduate majors then available in the US.

“I was so shy, I didn’t speak to anyone for four months,” Grant remembers. In addition to carrying a rigorous course load with plenty of math and engineering to master, she worked for a family as a housekeeper/maid/cook. She graduated in 1960 among the top in her class, Phi Beta Kappa. Because Portland offered little to someone interested in design, she headed to San Francisco where she found part-time work doing furniture renderings in the Herman Miller showroom. A chance conversation with Alexis Yermakov, director of interior design for Skidmore Owings & Merrill’s San Francisco office, led to a job offer, working with Yermakov’s staff. Yermakov was a talented furniture designer—he created the “Transition” line for Stow Davis—who had transferred from New York to direct interior design for SOM in San Francisco. English wasn’t his first language and filing and project management weren’t his strong suits. Grant recalls, “Alex hired me because I could type and had a pretty good command of the English language.”

In 1960, SOM was the pre-eminent American architecture firm. The company had completed or was about to complete five of its “canonical” buildings: Lever House and Manufacturer’s Hanover Trust (Fifth Avenue Branch) in New York; Connecticut General (with interiors by Florence Knoll), Bloomfield, Connecticut; and Chase Manhattan Bank and the Union Carbide building, also in New York.

Twenty-three-year old Margo Grant was entering a male-dominated world that was hierarchical and set in its ways. A few exceptions aside, most interior design questions on SOM projects were answered by a catalog of approved colors, textiles, carpeting, and furniture. Clients bought the “Skidmore look”, which was viewed as the industry standard. Deviations were not encouraged and were usually permitted only for the offices of C-level executives.

Yermakov left much of the daily details of running the IA department of the San Francisco office in Grant’s hands, which gave her an on-the-job crash course in commercial- building IA project management.

Because interior design was perceived as the “stepchild service” within SOM, management left the designers alone. Within limits, Yermakov and Grant enjoyed a relatively free hand. “Most of the time they just ignored us,” says Grant. Within six months of arriving at SOM, she was entrusted with her first major project: assisting Yermakov in completing the interiors of the offices Skidmore was building for the energy company, Tenneco, in Houston. The building, 32 stories and just over one million square feet, was designed by Chuck Bassett of SOM. Its light gray aluminum grid-like facade seems unexceptional today when seen against the daring architecture now in downtown Houston. But it was a landmark skyscraper for the time, and in Grant’s opinion, one of Bassett’s best works for SOM.

As SOM’s lead interior architect on the project, Yermakov insisted that the interior design of the Tenneco building not stick to the SOM script in terms of palette and materials. The executive suites would include green carpet, a color the chief architect for SOM, Gordon Bunshaft, didn’t like, and the office areas of the company’s four different sectors would be thematically distinguished by different wood finishes: oak, teak and so on. The look was distinctive and upbeat.

Working with Yermakov taught Grant some important lessons. First, it was possible to buck Skidmore’s tried-and-true ways of doing things, provided you offered a compelling alternative design. Yermakov left much of the daily details of running the IA department of the San Francisco office in Grant’s hands, which gave her an on-the-job crash course in commercial- building IA project management. She dealt daily with subcontractors; furniture designers; manufacturers of floor tiles, carpeting, and textiles; HVAC engineers; and other suppliers. She quickly mastered the complexities of pricing, ordering, and on-time delivery of thousands of products and components.

“Alex was a true teacher, introducing me to many of the vendors and contractors who became lifelong friends and allies,” says Grant. She would develop into one of the industry’s masterful client managers. Above all, the Tenneco project showed that Grant, at 24 years of age, could manage complex assignments, deal with demanding clients, and complete the job on time and on budget, with a minimum of drama. Houston, then emerging as a hotbed of innovative corporate design, would call Margo Grant back.

Above all, the Tenneco project showed that Grant, at 24 years of age, could manage complex assignments, deal with demanding clients, and complete the job on time and on budget, with a minimum of drama.

Mauna Kea 1963-65

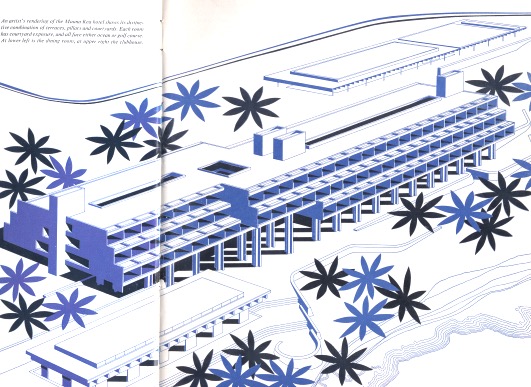

With the Tenneco project complete (the building opened in early 1963), Grant’s next assignment was a plum job: the Mauna Kea Hotel on Hawai’i (The Big Island). Hawai’i had become a state only in August 1959 and the islands were opening up. Behind Mauna Kea was Laurance Rockefeller of Rockresorts, the resort development company he’d founded in 1956. The company had already made its name specializing in hotel properties designed to blend with local landscapes and customs. The site of the 156-bedroom Mauna Kea was a slope overlooking a crescent of white sand beach on the Kona coast.

So prestigious was the project that Nat Owings, SOM’s founding partner, took on the role of partner-in-charge, while the lead designer was SOM veteran Chuck Bassett. Laurance Rockefeller requested that SOM’s Davis Allen be brought on as lead interior designer. Rockefeller knew Allen from his designs for the Chase Manhattan Bank headquarters, including the office of his brother, bank chairman David Rockefeller.

After Alexis Yermakov, Grant could not have found a better mentor than Davis Allen, who was committed to the principle of total design: Architecture includes everything from a structure’s external form to the disposition of interior volumes, furniture design, surface finishes, and utensils, and all must work together. As the foremost interior architect at SOM, based at the New York headquarters, Allen had free rein to consult on all the firm’s projects worldwide.

The Mauna Kea project would be split between SOM-New York, where Allen and Laurance Rockefeller were based, and SOM-San Francisco, where Grant was working. “I was called into the office and told, ‘Guess what, Margo, you’re going to New York to work for Davis Allen on the interiors. You’re going to be the project manager and junior designer.’”

Rockefeller, detail-oriented and perfectionist by nature—and willing to spend what it took—trusted Allen and Grant to execute the interiors as they saw fit. Allen insisted that he and Grant tour Hawai’i to appraise the design vernacular used in hotels and resorts. They found that nearly all new hotel construction bore the imprint of the design schemes of the major American hotel chains. Concessions to Hawaiian culture tended toward clichéd tropes of muumuus and leis. For Mauna Kea, Allen wanted to delve into the rich artistic traditions of Hawai’i, the Pacific Islands, indeed, of Southeast Asia. Shortly after Allen’s and Grant ‘s arrival in Hawai’i in November 1963, their team of two had grown to 14 people working on seven drafting tables.

Speaking of Allen’s approach, Grant said, “I was stunned. I wasn’t used to anyone thinking that big. He was thinking of the overall concept, but he was also thinking of the details.” (For this and other details of the Mauna Kea project, we’re indebted to Maeve Slavin’s monograph, Davis Allen: Forty Years of Interior Design at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Rizzoli, 1990.)

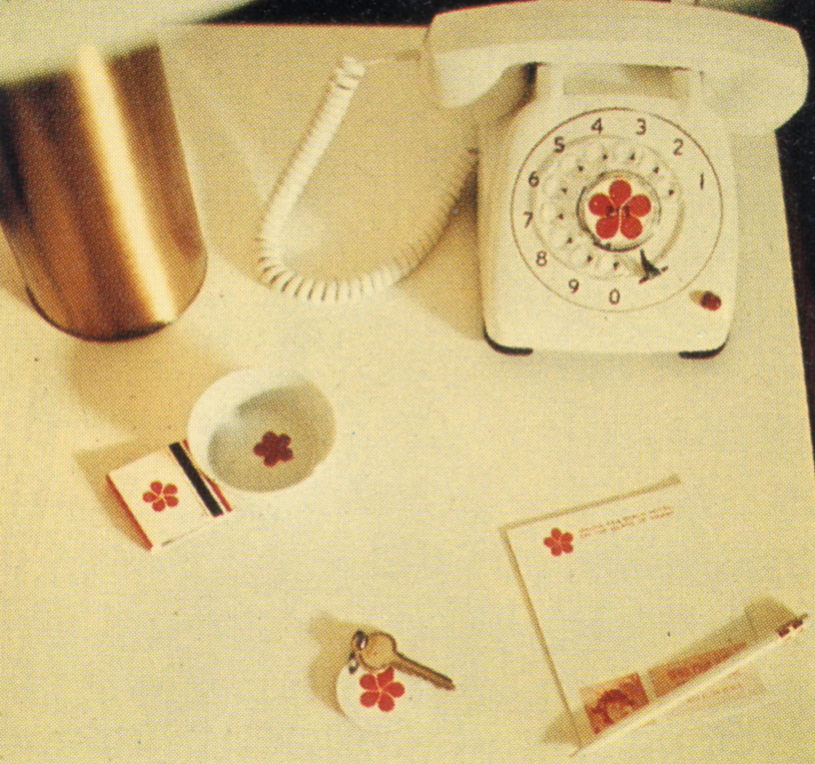

Leaving Grant in Hawaii, Allen went off, as he put it, “on a seven-week shopping trip to Hong Kong, Thailand, India, and Japan,” looking for design ideas, artwork, and native crafts to weave into rooms, hallways, and common areas. Grant managed the logistics of ordering Allen’s purchases and, when necessary, found workshops to produce designs in the quantities required. Each guest room had 42 discrete items, including ashtrays, vases, and handcrafts. “For the guest rooms alone, that’s over 6500 knickknacks to keep track of,” says Grant. When shipments were late, she scrambled to find a private air transport company to fetch them.

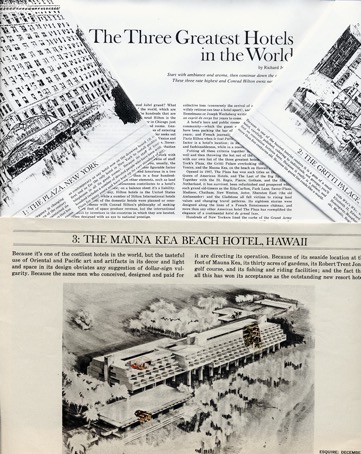

The results were exquisite. The tile floors were covered with lauhala matting from Pago Pago; beds, chairs, and doors were custom made of wicker woven in Thailand; unique traditional Hawaiian quilts adorned the hallways; staff uniforms, linens, and china were designed with a five-petal plumeria flower; shelves displaying beaten bronzeware lined the corridor walls. Travel writer and design critic for Esquire, Richard Johnson reported that the overall budget for the hotel building and interior was estimated at $15,000,000, making the per room cost nearly $100,000, one of the most expensive resorts built to that time. ($15 million today would be worth approximately $115,000,000, making the per room cost $746,000.)

She was a problem solver who worked comfortably with artisans as well as engineers and contractors.

When the Mauna Kea Resort and Hotel opened in 1967 it was hailed as a triumph of daring, sensitive, elegant design. Esquire’s Richard Johnson called it “an architectural and decorative masterpiece: Walking through it is like strolling through an open-air museum and art gallery.”

In later years Grant recalled, “That project changed my life.” The achievement of the project showed that Grant, as a woman working in a male-dominated culture at a top firm, could hold her own. It also showed the SOM managers and partners that she could be trusted with a major project, one of the most prestigious the firm had handled. Grant was recognized as cool-headed, quick on her feet. She was a problem solver who worked comfortably with artisans as well as engineers and contractors, men not always used to dealing with women as professional equals. These talents stood her in good stead in the decades to come.

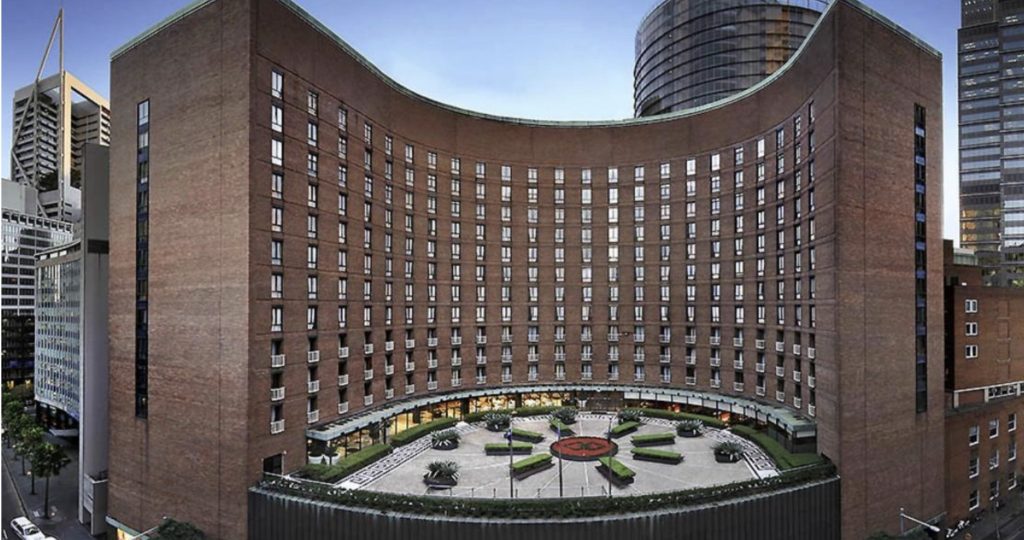

The Mauna Kea hotel project had barely started when SOM asked Grant to “pick up the pieces” of a mismanaged hotel construction project in Australia.

Grant’s career progressed steadily within SOM, each new project requiring more responsibility. Her assignments included some of the most important construction projects of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Mauna Kea hotel project had barely started when SOM asked Grant to “pick up the pieces” of a mismanaged hotel construction project in Australia. For two years she commuted between Hawai’i and Sydney, dividing her time between the two projects. Under her project direction The Wentworth hotel opened in Sydney in December 1966 with five-star status.

Bank of America- San Francisco

The 52-story Bank of America tower in San Francisco, completed in 1969, was the tallest—and most talked about—structure in the city. BoA, then the largest bank in the US, commissioned an all-star team of architects: Wuster Bernardi & Emmons, San Francisco’s leading firm; Pietro Belluschi, co-designer with Walter Gropius of the PanAm Building in New York; and SOM to assist with the design and manage construction and interior design.

As Grant worked on the BoA corporate office design, a young architect who had recently founded his own firm was working with the realtor to lease the remaining office space. He was Arthur Gensler. This was not the first time his work had overlapped with Grant’s. A few years earlier they had both worked on the interiors of the Alcoa building, also in San Francisco. Although they worked on different aspects of the project, in some respects the Bank of America building was their first collaboration. The design included 52 floors with 38 different floor plans. This was extremely impractical if a client wanted to rent more than one floor, as each floor had to be designed separately, incurring unnecessary cost. Grant got to work and reduced the number of floor plans to 26. Art Gensler may not have been aware that Grant’s change eased his job of renting the space. In a few more years they would join forces.

Without Arthur Gensler, Margo Grant might not have left such a lasting mark on interior architecture and the role of women in the specialty. Without Margo Grant, Arthur Gensler would undoubtedly have created a successful design firm, but the firm might not have grown or attained global reach as quickly as it did.

When Grant joined Gensler she already had 13 years of intense project experience in interior architecture and design, working at the highest level for major clients. Arthur Gensler, trained as a traditional architect focused on a building’s shell, was a generalist whose expertise covered a wide array of projects. His experience on interiors was mainly in tenant work, helping realtors lease space in new construction. [For material on Arthur Gensler’s career and early years, we are greatly indebted to the series of interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2014 as part of the Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley referenced below.]

In the design jobs he’d held since graduating from Cornell in 1959, his only corporate interior assignment was the lobby of the Union Carbide office at Rockefeller Center. Frustrated by the relatively unrewarding work New York-based firms offered, Gensler took the advice of a teacher at Cornell and headed to San Francisco. After a brief stint at Wurster, Bernardi & Emmons, he decided to start his own firm and incorporated it in April 1967 as “M. Arthur Gensler, Jr. & Associates.” The associates were his wife Drew, who managed the books, and two other designers, Jim Follett and Hal Edelstein.

Gensler and Grant might have remained mere acquaintances had Gensler not landed a commission to design the interior space of the Pennzoil complex in Houston in 1973.

Gensler and Grant might have remained mere acquaintances had Gensler not landed a commission to design the interior space of the Pennzoil complex in Houston in 1973. An imposing 36-story, two-tower structure with a roofline angled at 45 degrees, designed by Philip Johnson, Pennzoil Plaza became one of the most high-profile design projects of its time. Gensler, who remained in San Francisco to manage projects there, had set up an office in Houston with another designer, but he needed help. Grant was in Buffalo working on a project when Gensler called her. She flew to San Francisco where “he wooed me over lunch,” says Grant. Art Gensler hired her in spring 1973.

The move may seem to have been inevitable, but Grant was giving up a great deal. She had a secure position in one of the world’s leading architecture firms, which had trusted her to manage the interior design of some of its most important projects. In business for more than 40 years, SOM had offices and commissions in progress all over the world. Grant had good relationships with her colleagues in SOM’s interior design department. The challenge was one of professional growth. “I did have access to the partners in the firm,” Grant told an interviewer, speaking of SOM. “It’s just that I had access to them relative to a project, not relative to the fact that I had an idea.” She’d hit the glass ceiling and was anxious to get out. In Gensler’s firm, Grant found her home.

She’d hit the glass ceiling and was anxious to get out. In Gensler’s firm, Grant found her home.

Once installed in Houston, Grant quickly proved her worth. Originally, Philip Johnson had wanted to design the interiors of the Pennzoil executives’ offices himself, but Art Gensler was keen to keep that plum assignment for his team. Although Johnson was insistent, Grant had established such a strong rapport with the client, Pennzoil president Hugh Liedtke, that he gave the entire interior design project to Gensler. Gensler recalls, “They said, ‘No, no, you do the whole thing,’ because they got really comfortable with Margo.”

"She was an incredible relationship-builder." - Arthur Gensler

In addition to her client skills, Grant brought to Gensler a crucial project-management practice she’d learned at SOM. Building 3D models was not a tool used by Gensler before her arrival. “I said to Art, ‘How are we going to sell this design for Pennzoil when they can’t see it,’” she recalls. “When you have executive offices, they don’t respond well to renderings or floor plans, but they do respond to models.” Grant had mock-ups built to show to the executives; the practice was adopted company wide.

Pennzoil was a success, and Gensler and Grant remained good friends with Liedtke and his wife, and with Jerry Hines, Houston’s most important developer. Gensler made Grant a company vice president after the first year. As the pace of work increased, Grant found herself specializing in finance clients and law firms. The Pennzoil Plaza project caught the attention of the Houston law firm Baker & Botts, which engaged the Gensler firm for its interiors. They were followed by Covington & Burling in Washington DC, which led to Gensler’s being engaged by other firms and consultancies in the capital. By 1983, Gensler had enough business in Washington for Grant to open Gensler’s office there, followed by Boston, where she redesigned the offices of a leading law firm, Hale & Dohr, among others.

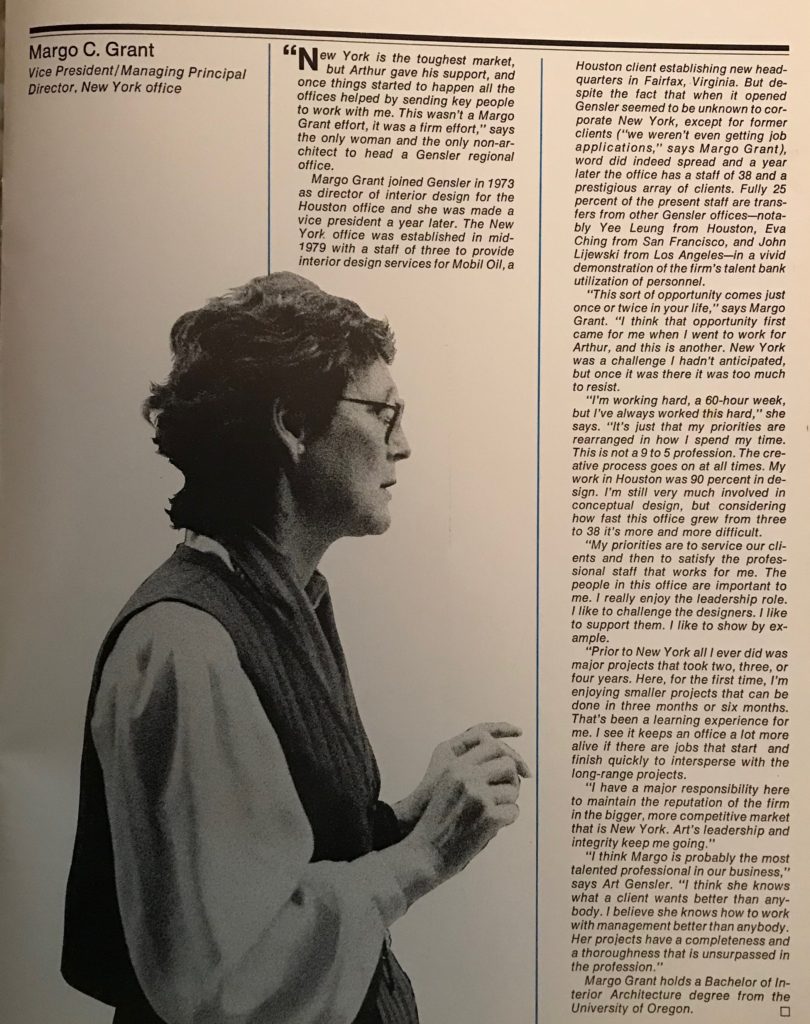

Grant became something of a specialist in opening Gensler’s regional offices. The most important of these was New York, which she ran singlehandedly for many years. Her prowess with banking clients took her then to London, where she opened Gensler’s office there. Through the 1990s her corporate design work for Gensler continued to flourish, while she took on greater responsibilities in management and in mentoring younger designers. After thirty on years at Gensler, as the company is now known, Grant retired in 2004. Along the way, Arthur Gensler recognized Grant’s contributions by naming her a managing partner—one of a handful who planned company strategy—company director, and vice chairman with shares in the company.

Does Margo Grant see herself as an icon? The word makes her a little uncomfortable. When pressed, she recognizes that she was a trailblazer and is quick to credit Arthur Gensler for hiring her when many, even most, male executives wouldn’t have taken on a woman for such prominent a role and for allowing her to grow as the company grew. She also credits Drew Gensler, Arthur’s wife, for being a supporter. As Grant told Jennifer Busch, editor-in-chief of Contract , “Trust and respect—he gave me that. [Drew] was a true advocate, and a very important influence on Art.”

Margo Grant gave so much of her life to interior design and Gensler, it’s hard to imagine her having time to explore passions outside of her profession. But explore she has, collecting antique silver from the Arts and Crafts movement (late 19th and early 20th centuries). Appropriately enough, her passion grew out of her work with a client, Goldman Sachs, as she explained to the New York Times: ”One of the partners asked me to build a case for an unusual piece of antique silver, and I got interested. I started going to auctions and seeing dealers.”

She donated a significant portion of her collection to Portland Art Museum in 2002 and 2003.

A less discussed aspect of Grant’s collecting is her passion for artisan-made 18th to early 20th century American footstools. Her collection of these overlooked pieces of furniture at one point numbered over 300. Their appeal may say something about the collector herself. They are humble, sturdy, easily transported and adaptable to multiple uses. As she told an interviewer, “You could put your feet up, stand on them to reach high shelves and for children to sit on in front of the fire. They were satisfying.” Practical, humble, and down to earth, in other words.

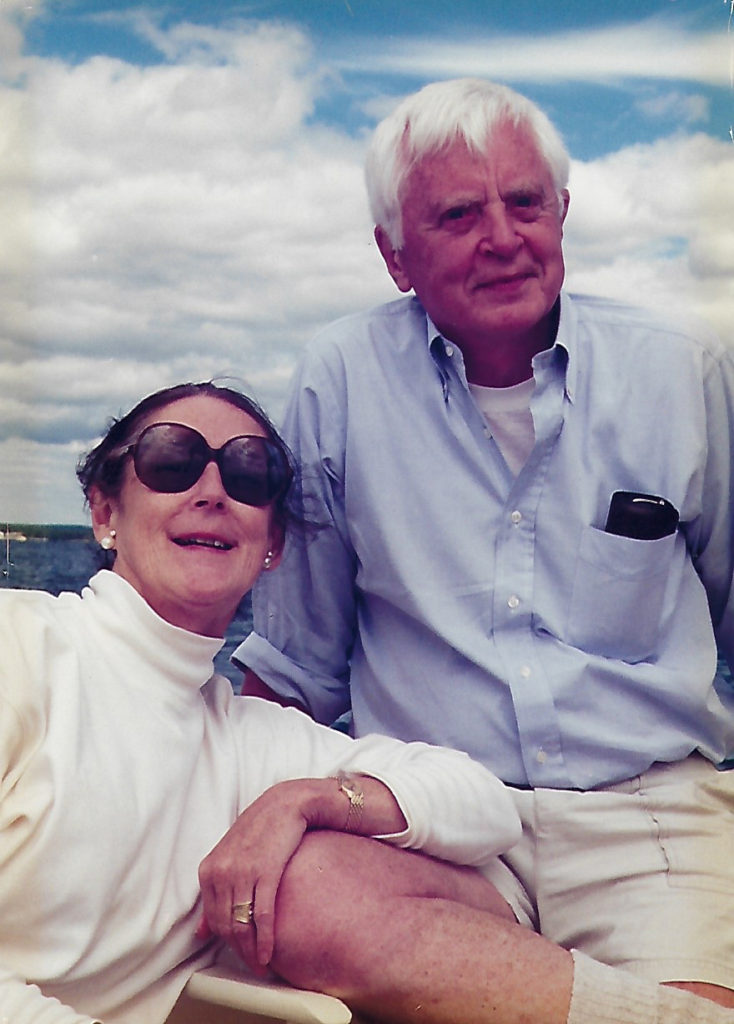

It is poignant that Grant acknowledges as a major regret that she did not meet her husband earlier. She married John Walsh, president of his family’s apparel business, in 1994. They had four years together until his death in 1998. As she told Jennifer Busch of Contract magazine, Grant considers her brief time with him to have been the most significant of her life.

“When I graduated from college in 1960, women could either be a nurse, a teacher or an airline stewardess,”

“When I graduated from college in 1960, women could either be a nurse, a teacher or an airline stewardess,” says Grant. Through her talent, hard work, creativity, and seemingly magical client-management skills, Margo Grant was instrumental in the creation of a new profession and women’s place in it. When she retired, she was a managing partner of one of the most important architectural firms in the world.

In 2002, Contract named Grant a design “Legend.” This was a newly created category of award, Jennifer Busch explained, which was intended “to honor individuals whose career achievements and contributions to interior design and architecture have served to raise the level of practice and set outstanding examples of talent and professionalism for the rest of the industry.”

Profiling Grant, Busch collected testimonials of colleagues who had worked with and been mentored by her:

“I started with Gensler in 1983, and I had the good fortune to sit not far from where Margo’s office was. Observing her work habits day to day, seeing how clearly focused she was on doing a great job, knowing she was so accessible to the staff, she was an incredible example of leadership.” — Diane Hoskins, current co-CEO, Gensler, Washington, DC.

“She forced clients to look at good design whether they wanted to or not. Her driver was serving the client.” — Tony Schirripa, Gensler colleague, later CEO of Mancini-Duffy.

“The thing she’s brought to the table is her interest in benchmarking industries and understanding the business ramifications of design to help clients make informed decisions, rather than arbitrary ones.” —Arthur Gensler

The design industry has honored her in numerous ways. In 1987, Interior Design, named Margo Grant to its Design Hall of Fame. For her contribution to the company and the industry, Gensler named an award for Grant. The Margo Grant Walsh Award, given annually, “recognizes projects that achieve design excellence through cost-effective solutions, often through the inventive use of off-the-shelf components.”

In 2005, the International Interior Design Association named Grant and Arthur Gensler as two of “Five Living Heroes who changed the face of interior design.” Praising her achievements, the Eileen Watkins of the IIDA wrote, “Margo Grant Walsh has become one of the most powerful and influential women in American architecture and interior design. She not only pioneered the way for women in her field but helped establish the profession as it is defined today.”

She not only pioneered the way for women in her field but helped establish the profession as it is defined today.

References

Jennifer Thiel Busch. Interview with Emanuela Frattini Magnusson, June 12, 2019.

Jennifer Thiel Busch. “A Titan of Industry: A Tribute to Margo Grant Walsh.” Contract 44.1 (2002): 46-9.

Arthur Gensler. “Art Gensler: Building a Global Architecture and Design Firm.” Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2014, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2015.

Margo Grant. Interviews with Emanuela Frattini Magnusson, October 2019 and Emanuela Frattini Magnusson and Sam Perkins, December 27, 2019.

Margo Grant. “Mauna Kea Beach Hotel. 40 Years of Aloha.” 2006

Margo Grant. Women in Architecture. Gensler & Associates Architects, 2005.

Richard Johnson. “The Three Greatest Hotels in the World,” Esquire, October 1, 1973.

Wendy Moonan. “A Modernist Sees Luster In Old Silver.” The New York Times, February 21, 2003.

Timothy A. O’Brien, with Margo Grant Walsh. “Collecting by Design—Silver and Metalwork of the Twentieth Century from the Margo Grant Walsh Collection.” Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2008.

The Office of the Secretary of State of California. Articles of Incorporation. “M. Arthur Gensler, Jr. and Associates, Inc. April 4, 1967.

Zahid Sardar. “Interior architect kicks back by hunting for old stools / Footstools, itinerant art forms on view at SFO’s International Terminal gallery.” San Francisco Chronicle. August 24, 2005.

Maeve Slavin. Davis Allen: Forty Years Of Interior Design At Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Rizzoli, New York. 1990.

Andrea Truppin. “Chateau Margo.” Interiors (158, 9), September 1999.

Eileen Watkins. “Living Heroes—Five who changed the face of interior design.” Perspective (IIDA publication) Summer 2009.

Author

Sam Perkins is a New York based writer and board member of SilentMasters. For his full bio please see here.