Paolo Riani

1937 - presentFrom 1960 to today, Paolo Riani ( b. 1937) has traveled and worked in Japan, the USA, Russia, Middle East, Argentina and, of course, Italy, particularly Tuscany, as an architect, teacher, and photographer. Riani’s designs—municipal buildings, private homes, multi-use commercial centers, and more are an enduring legacy. The best of them seem as fresh today as newly minted coins.

"Good architecture is to be found when the reality of design meets the reality of life."

Riani has also been an important evangelist and advocate for designers overlooked or disdained by the mainstream. In books and articles and in the classroom, Riani has aimed a critical eye on projects well-publicized and unheralded. He promoted the work of an architect not widely known outside his native Japan, Kenzo Tange, whose designs of private and public spaces in post-World War Two Japan profoundly influenced the reconstruction of that country. Riani was among the rare academics to champion the work of, John Portman at a time when the design cognoscenti considered the work of the American designer-developer vulgar.

However, Riani’s name is never listed among the professionals of power and influence in the world of design. To understand his contribution, you have to follow his traces in his writings, photographic images from his travels around the world, designs, projects, constructions and, if you’re lucky, to listen to the tales of his life.

For Paolo Riani, architecture emerges from understanding how we live and the raison d’être of objects around us, providing concrete solutions to individual human needs. If architecture is defined as the organic outgrowth of the everyday lives of communities – with specific reference to the Florentine Organic School and to classic Japanese architecture – then every strand in Riani’s life converges upon architecture. As he would say, “Good architecture is to be found when the reality of design meets the reality of life.”

Paolo Riani was born on September 8, 1937 in Barga, Italy, a medieval hill town in the province of Lucca. Quite early on, with his father’s encouragement, he devoted himself to drawing and painting. When Paolo was 15, his father gave him a Leica M3, a gift of immediate and lasting value.

Photography became inextricably bound up with a desire for travel and discovery, and later, with a passion for design and construction. The young Riani traveled through Europe, Asia and the Americas, searching out the works and places that most intrigued him. His photographs, sketches, and notes document his exploration, discoveries, and encounters; travel as plan, as design.

In 1959 Riani enrolled in the architecture department of the University of Florence. There he met and became the teaching assistant for Edoardo Detti, an influential architect and professor, who eventually became Riani’s mentor. A teacher on contemporary urban design, Detti, Florentine born and bred, was also an energetic proponent of the traditional architecture of Italy, especially the communal spaces, squares and piazzas, which he documented in a number of books. This meshed neatly with Riani’s interests. In his final years at university, Riani, working with Detti, was put in charge of designing the master plan for San Miniato al Tedesco in Pisa and the renewal plan for the Borgo del Ponte area of Massa on the Ligurian coast.

Throughout his career, Riani used his talents as a writer and a curator of exhibitions to absorb lessons from those he considered architectural masters of the day. The first instance of this came in 1963, when, still a student, he was selected to curate the architecture section of the Florentine exhibition of works by Le Corbusier, a major influence in the formal and figurative language that Riani would develop. He later co-wrote a monograph on Le Corbusier’s work (Le Corbusier, Ed. Sadea Sansoni, Florence, 1966).

Two years later Riani helped organize an exhibition of the work of Alvar Aalto (1898-1976), the second great architect Riani chose as a master. The summer before the exhibit, Riani suggested to his father that they travel to Norway’s North Cape by way of Finland—an exciting adventure, undertaken in his new Triumph Spitfire. Along the way, Riani made sure to stop at as many of Aalto’s creations as possible. A year later in Florence, Riani was able to spend time with the now elderly master, and came away with nuggets of instruction and encouragement: “Don’t be apologetic, you can put two bricks together and make them sing.”

Diligence and commitment in the studio and school began to bear results. Riani took first prize in a competition for a nursery school in La Spezia, and won a grant from the Adriano Olivetti Foundation to specialize in city planning. In 1965, Riani graduated from the University of Florence after completing a thesis on residential development near the harbor Livorno.

After a hard, searching meditation on the Italian political scene—political and social unrest in the 1960s had slowed major construction to a near standstill—Riani decided to leave Italy and, with it, the safety of an academic and professional career. His dream was to travel to Japan, at that time home to cutting-edge architecture and urban design. He was particularly drawn by the daring theories of Kenzo Tange, the third of his admired masters. Tange, a greatly respected talent who numbered Walter Gropius among his admirers, had made his name with his first, very high-profile commission—the daring, monumental design of the Peace Park in Hiroshima (1950-1964), built to commemorate those who’d died in the bombing in 1945.

To meet Tange, to see the actual spaces in which his works were set, was a long-cherished desire, which Riani now felt with a heightened sense of intellectual and professional urgency. Riani arrived in Tokyo in August 1966. The Japanese master and the young Italian designer formed an immediate bond.

Tange soon invited Riani to become an assistant in his master planning course at the University of Tokyo. Thus began a transformative sojourn in Japan.

Though more than 20 years apart in age, the two designers had much in common. Like Riani, Tange was an unabashed Corbusian. Both men were born into societies that held fine architecture, design and craftmanship in the highest respect; both their respective countries were rebuilding after years of devastating war and fascistic, anti-democratic government; both countries were blessed with an energetic generation of architects struggling to synthesize architectural traditions with new design concepts and construction materials; both architects felt that the environments they designed could help create societies that were democratic, open, and modern.

After contributing as an associate designer to the master plan of Kyoto, Riani executed two prominent works on his own: a night club, called Caesar’s Palace, in downtown Tokyo, and the Tokyo headquarters and showroom of MEC Design International, a furniture company. Both buildings had small footprints, hemmed in as they were by the crowded landscape of downtown Tokyo, but both showed daring design flair.

The Caesar’s Palace building from 1969 was not large, only two stories tall, and under twenty meters wide. The upper part of the façade was a flat, windowless, brutalist concrete wall, below which sat an undulating, sensuous wave of walls finished in mirrored gold a small scale example of beauty and elegance.

The same could be said of another piece of Riani’s architecture in Tokyo’s fashionable Aoyama area, the MEC Headquarters, completed in 1971. The structure still stands out strikingly in one of Tokyo’s busiest and most attractive streets. In an age when the use of mirrored-glass windows were rarely used in commercial construction, this design had a completely reflective façade—Riani called it a “non-façade”—with all its mullions cut on a diagonal, as was the entrance door. In a nod to what would later be called experiential shopping, Riani included elegantly designed lounge, cafe and bar areas. Throughout the interior, the sober materials, stainless steel and dark gray marble, complete the look of quiet refinement. While Caesar’s Palace is unfortunately, gone, the MEC still stands out as an urban jewel amid much uninspired development going up today.

Apart from brief visits to Italy, Riani remained in Japan for six years. It was a period of rich emotional discovery that indelibly shaped his sensibility, his mode of perceiving reality. He also used his time in Tokyo to travel throughout Asia, documenting landscapes, buildings, and cultures which he chronicled in a steady flow of articles on travel, architecture and design. During his time in Japan, he also met Noriaki Kurokawa, the 30-year-old founder of the Metabolist design movement, with whom he would form a lifelong friendship, and the designer Junko Enomoto, who accompanied him in his travels around the world and worked alongside him for several years.

Riani’s enchanted yet lucid observation of Japan deepened through encounters, conversations and reading—contributed greatly to knowledge about that country in Italy. In addition to mastering the language, he grasped Japanese design vernacular with a fluency that his hosts greatly respected, awarding him the Shinseisaku prizes for architecture in 1966, 1967 and 1968. Riani repaid those honors in 1969, by organizing the Contemporary Japanese Architecture exhibition in Orsanmichele in Florence, and editing the catalogue (Florence: Centro Di, 1969). He followed this with his book, Kenzo Tange (Sadea Sansoni/Hamlin, U.K.,1969, 1970).

In 1971 he returned to Florence, where he became Libero docente (PhD) in architecture. Yet his stay in Italy would not last. Awarded a Fulbright grant for research in the United States, Riani left for New York. Since early childhood America had been part of Riani’s imagination, drawn from stories about his grandfather Amedeo Pieroni, who in 1890 emigrated to the U.S. and became a successful hotelier. For Riani, America represented not a myth but rather a world of opportunity.

Among his most significant acquaintances in New York was Mildred F. Schmertz, senior editor at Architectural Record, who introduced him to Paul Rudolph, Philip Johnson and Aldo Giurgola. He came to know Massimo and Lella Vignelli, Tony and Angela Palladino, and Miles Davis, who told him one night: “Do your thing man… just be sure what your thing is.”

Miles Davis, who told him one night: “Do your thing man… just be sure what your thing is.”

At Columbia University he received a master’s degree in architecture and city planning and became associate professor of architecture. He pursued professional activity, on his own and as a consultant in the offices of Katz Waisman Blumenkranz Stein & Weber where he designed the campus of Kingsborough Community College (KCC), in Sheepshead Bay, (L.I) and later at Welton Becket Associates, for whom he designed the World Trade Center in Moscow. Both projects called upon Rinai’s ability to integrate compelling design for mass use within large outdoor spaces. This was particularly true of the KCC project, which is situated on a spit of land surrounded on three sides by water. The Moscow World Trade Center is also on the water—on a bend in the Moskva River. It combines an 11-story convention center with a mixed-use business and hotel center. The use of interior space—it is the city’s largest convention center—remains fresh after half a century.

Life in the megalopolis stirred a longing in Riani for other opposite spaces: the desert. He acted on this desire when he was offered a job in Lebanon for the Citicorp Estate Company to design the master plan for the Ramlet El Baida area in Beirut. His stay in Lebanon was cut short a year later by the outbreak of civil war. In 1976 Riani returned to Italy and decided to stay. He established a studio of architecture and international consulting in Florence on Via Sant’Egidio, from where he continued activity in Arab countries, overseeing planning for new towns in North Africa and sports centers in Saudi Arabia among others. In the 1980s, Riani divided his activity between Italy, the USA, and Japan, designing numerous industrial, commercial and government buildings in Italy and private residences in the U.S. and Japan.

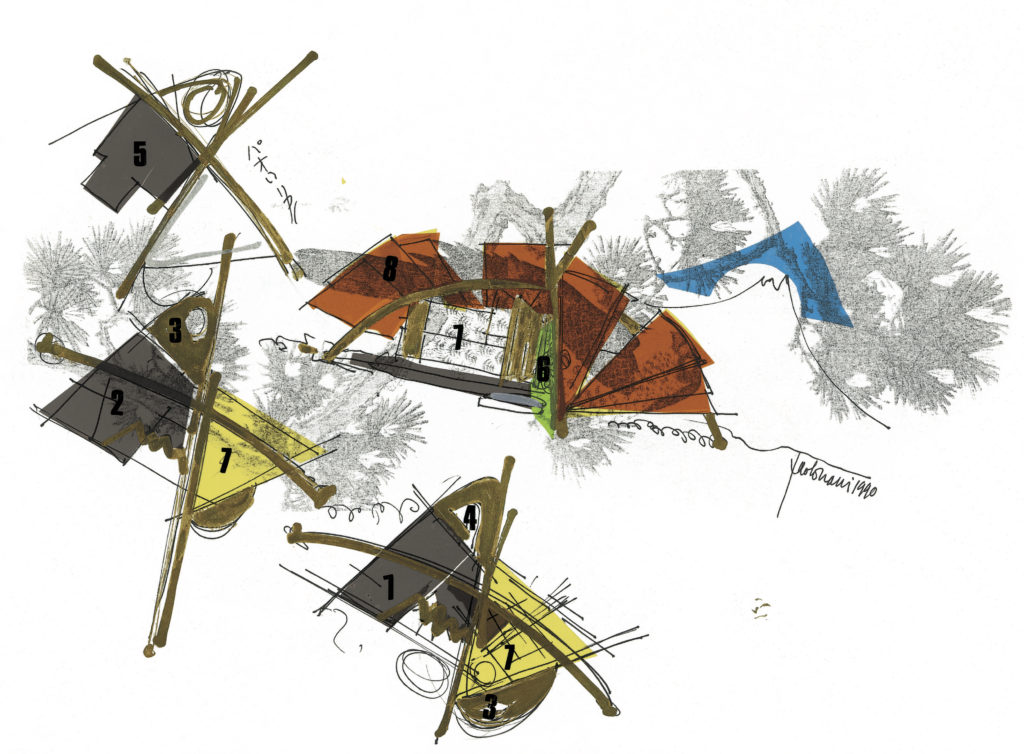

Two projects from 1980s stand out: the Compagnia delle Pelli offices and showroom outside Bergamo and the GIFAS buildings in Lucca and Dusseldorf. Neither is especially grandiose, but each is executed with clean elegant line and detail. Riani also reveals an understated color palette for the external materials.

Reviewing the Compagnia delle Pelle commission in Arca, Maurizio Vitta, noted that Riani’s rigorously right-angled façade created a an almost two dimensional abstract painting-like effect. The interior of lightly veined gray marble, brushed steel and tan leather, lit by circular skylights provided an elegant, timeless feel.

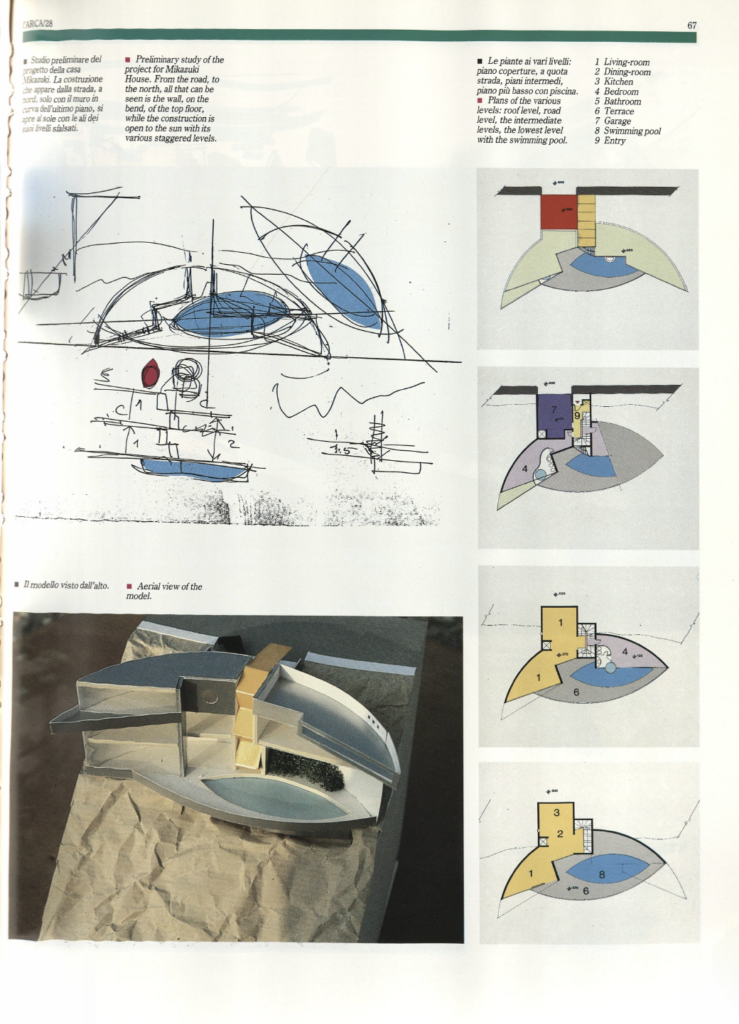

The GIFAS buildings in Lucca came with special requirements: the German manufacturer of electrical generator and equipment needed a business office with two private residences attached, one on either side. Drawing inspiration from the form and look of GIFAS’s electrical generators, Riani punctuated the exterior section panels (Alucobond and Solarsiv silver glass) with large convex windows that resemble massive steel bolts and used pompeian red for the external pillars and doors. He softened the sharply angled panels and cantilevered roof line with discrete sinuous lines and curves. “The outcome … is a surprise,” Riani wrote, later. “It goes beyond the initial intentions and the house rises up amidst the greenery, like one of those enormous heads on Easter Island, not in stone, but clad in aluminum, with a vivid red entrance rather like an open mouth.” (Arca, January 1991, pp. 52-57) It looks as fresh today as it did three decades ago.

Riani has always used the printed word as much as his designs to make his point.

In the first years of the 1990’s he was especially active in publishing. John Portman (l’Arcaedizioni and MIT Press, 1990) was a collaborative work incorporating a lengthy interview between critic Paul Goldberger and Portman. In his detailed analysis of Portman’s work, Riani reassessed the controversial architect-developer whom Riani had met and admired in the US. Portman’s large scale public architecture , especially, the Embarcadero Center in San Francisco and Peachtree complex in Atlanta (1965-1991)—Riani called them “cities within cities,”—were decried as “flawed fortresses,” cut off from the downtown areas they occupied.

Portman, Riani wrote in his introduction, “was not popular with the American Institute of Architects because he was also a developer,” and mistrusted for “his mixing financial operations with design.” But as early as 1972, as an associate professor in the design school at Columbia, Riani was an advocate of Portman’s daring use of public space and argued that the buildings and the complex surrounding them were welcoming and uplifting.

My students and I liked John Portman. We liked his courage and his imagination. We liked the scale of his projects, which were experiments that allowed us to verify the need for design on an urban scale that all of us felt. We preferred these merits to the sterile intellectualism of some of my controversial colleagues at the time, or the anonymous stands of people who adhered to the “less is more” philosophy, accentuating cold formal aspects rather than rare poetic content.

The multi-story atrium lobby Riani included in his design for the Moscow World Trade Center seems directly drawn from Portman’s work

The professional situation in Italy, ever more difficult for anyone who shunned compromises, was such a source of bitterness and fatigue that Riani resolved to move with his family to the USA. He was on the brink of leaving, when he was offered an important reason to stay—he was asked to run for political office. In April 1994 he was elected senator of the Italian Republic, and for ethical reasons he chose to take a leave from practicing architecture. In February 1996 he led the Italian parliamentary delegation to the United Nations in preparing for the world conference on human habitats (HABITAT) and, as committee chair, drafted the national report for Italy. In 1996 he became a member of the international association Global Parliamentarians on Habitat. At the end of the 12th Legislature (1997), he withdrew from the political scene and returned to architecture.

Now in his 80s, Riani’s projects in the new millennium have come full circle, returning him to his roots in western Tuscany and the Ligurian coast, where his life in design began: reconfiguring shipyards and a traffic interchange in Viareggio, elegantly and efficiently integrated between the Apuan mountains and the sea; restoring a 2500-acre agricultural estate in Peccioli (Pisa), where the project integrates landscape design and environmental renewal; conceiving a Montecatini parking complex in the form of a city; completing a commercial shopping center in Viareggio and a winery resort in Montecarlo, Lucca. Further afield, in Cagliari, Sardinia he just finished an urban renewal integrated into an overall plan for Mediterranean ports. Whatever the project, he’s drawing, designing, feeling the needs of the citizens who use the space, as he’s always done.

PUBLICATIONS and HONORS (partial list)

BOOKS

Architettura giapponese contemporanea. Florence, Orsanmichele, 1969. Catalogo a cura di Paolo

Riani. Introduction by Fosco Maraini and Carlo L. Ragghianti.

Le Corbusier, Paolo Riani and V. F. Pardo, Ed. Sadea Sansoni, Florence, 1966.

Home from Home. Travel stories, Electa/Mondadori, Milan, 1991.

I Fratelli Pieroni da Barga a Boston (1993) by Bruno Sereni, prologue by Paolo Riani. Edizioni Il

Giornale di Barga, 1993.

Kenzo Tange. London, New York, Hamlyn, 1970.

John Portman. Paolo Riani, Paul Goldberger, John Portman; principal photography by Michael

Portman and Timothy Hursley. Milan, L’Arcaedizioni, 1990.

EXHIBITIONS

2005 – Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Florence): “Paolo Riani: Uncharted Territories;” also shown in New York, Tokyo, and Buenos Aires.

2010 MARQ, Festival de la Luz, Buenos Aires : “Babel,” an exhibition of Riani’s photographs.

2011 IVAM, Valencia, Spain: “Paolo Riani:Un Mundo di Arquitecturas,” a retrospective.

AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS:

1966, 1967, 1968 – Shinseisaku Prize

1970 – Named a member of:

— International House of Japan

— The Shinseisaku Academy

SOURCES

Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese Architecture, by Kenzo Tange, introduction by Walter Gropius, photography by Yashuhiro Ishimoto. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1960.

Città murate e sviluppo contemporaneo: 42 centri della Toscana, Edoardo Detti et al, Edizioni CISCU, Lucca, 1968.

“Caesar’s Palace” by the editors, Architectural Record, 1973 Aug., v. 154, n. 2, p. 103-107

“Stores and shops: Fractured reflections evoke curiosity and awe” by the editors, Architectural Record, 1973 Aug., v. 154, n. 2, p.132-133.

“The new architecture of Florence” by the editors Architectural Record, 1974 Feb., v. 155, p. 97.

“Sports center [project], 1975, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; architects: Paolo Riani Associates” by the editors, Domus, 1979 June, no.595, p.34.

“Paolo Riani: Multi-use building at Viareggio, Italy” by the editors, Architecture & urbanism, 1984 Oct., no.10(169), p.71-76.

“Fabbrica e uffici con residenze in Lucchesia; Factory and offices with residence” by Paolo Riani, Arca, 1988 Jan.-Feb., no.13, p.48-55.

“Ambiguità e iconismo per l’industria: Ambiguity and iconism for industry,” by Maurizio Vitta. Arca, 1990 Dec., no.44, p.58-63.

“Casa e fabbrica: Dovetailing home and industry” by Paolo Riani, Arca, 1991 June, no.50, p.52-57.

“The new architecture of Florence” by the editors Architectural Record, 1974 Feb., v. 155, p. 97.

Author

Alessandra Coppa is an architect, journalist and publicist living in Milan. She has published monographs on Giuseppe Terragni, Mario Botta and Adolf Loos among others for Sole 24 Ore. Besides her writing activities she is teaching Contemporary Architectural History at the Milan Politecnico and created the Architecture and Design publication series for Corriere della Sera, Milan’s daily newspaper. Sam Perkins is a New York based writer and board member of SilentMasters. For his full bio please see here.