Junzo Yoshimura

1908 - 1997Junzo Yoshimura could be described as the most classical among contemporary Japanese architects. The foundation of his approach to composition lies in the combination of basic building elements into a hierarchical virtuosity, which transforms the archetype into many different iterations, depending on the needs that the structure must fulfill.

Sam Perkins

Translation by Emanuela Frattini Magnusson

Junzo Yoshimura could be described as the most classical among contemporary Japanese architects. The foundation of his approach to composition lies in the combination of basic building elements into a hierarchical virtuosity, which transforms the archetype into many different iterations, depending on the needs that the structure must fulfill.

Yoshimura’s very own interpretations of the shoin-zukuri stylistic elements are the wellspring of his design process – in his words, “If you want to study Japanese architecture, don’t study the sukiya style. Begin by studying the shoin style” – creating the connection between Eastern and Western cultures: a hinge between tradition and modernity.

Yoshimura’s statement is key to understanding his esthetic. Shoin style evolved in 14th through 16th century out of designs used for monasteries and the villas of shoguns or other notables. It is characterized by large central room, used as a study or as a reception area (shoin means study), with square wooden pillars supporting a double-height ceiling, shelves for books and recessed alcoves (tokomoma) with desks. Sukiya style evolved out of shoin style beginning in the 16th century. More modest in scale, it relies on smaller rooms and is more adapted to use as a private residence. Shoin style, in the words of David and Michiko Young (The Art of Japanese Architecture 2007), brings together “élite and commoner traditions.”

Yoshimura’s emphasis on the importance of shoin style can also be inferred from the fact that sukiya style fundamentally, in the words of Japanese architectural historian Teiji Itoh, is “concerned primarily with interior design.” Sukiya design idiom has a very limited vocabulary when it comes to structural guidelines for the modern architect. “No attention was paid to the placement of posts or beams or to the manner in which the load of the roof would be supported…Structural problems of framework …were someone else’s responsibility.” (Itoh, pp. 220-221).

Shoin style’s broad range of architectural vocabulary and contrasting volumes—from intimate to spacious—are essential components of Yoshimiura design.

Equally important to Yoshimura’s esthetic is his profound connection with nature, experienced as an organic background, which gives life to all creatures, and expresses the perfect unity between spirit and the material world. With these principles as foundation, Yoshimura’s oeuvre stands out in the context of modern architecture through its expression of a few fundamentals: a hierarchy of composition that generates harmonious geometric systems, simplicity and purity of materials, the profound sense of professional ethics, and, as a central goal for every project, the user’s sense of well-being.

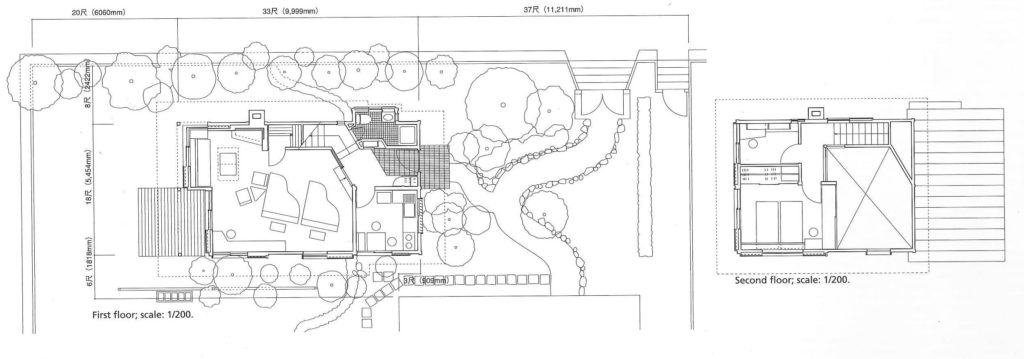

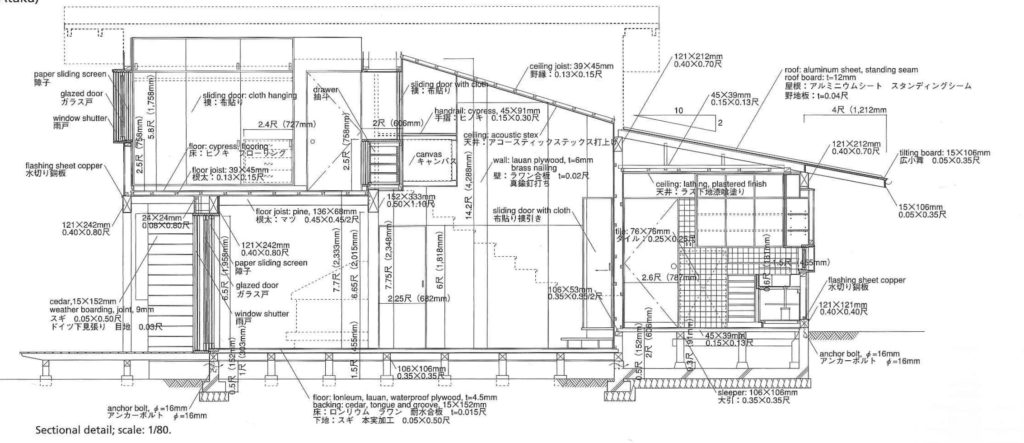

House at Jiyugaoka, Meguro, Tokyo 1955

The small residence and music studio is situated within the confines of a rectangular garden in Jiyugaoka, in the district of Meguro.

What is purity in architecture? It is building materials used honestly, and structures composed only of the elements necessary.

“What is purity in architecture? It is building materials used honestly, and structures composed only of the elements necessary. The role of a column is always to support the roof; the framing of a shoji screen is a molded pattern, as well as having a firm structural role. Those compositions are extremely simple yet produce an orderly beauty. That is what I mean by purity.”

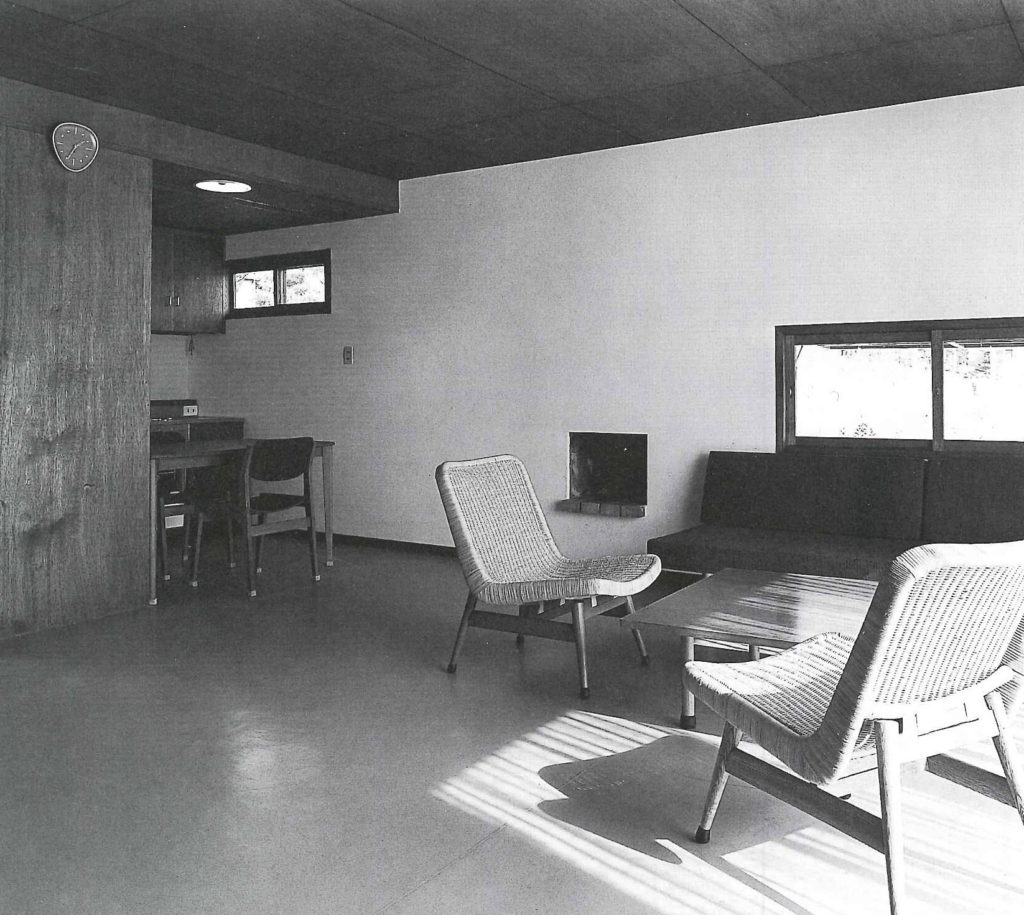

This small, two-story wooden structure (59,9 sqm/650 sq ft) is defined by a rectangular profile shaped. Inside, the main room is dedicated to the study and playing of piano and represents the fulcrum of the spatial distribution.

The difference in elevation between entrance and interior, the angled wall which cuts the view only to expand it through the large windows that open up onto the garden, the double height volume where a mezzanine inserts itself and lowers the living room ceiling—all these elements extend the modest dimensions of this dwelling.

The impeccable execution of construction and detail allows the different natures of materials to harmonize and to modulate the intensity of light. The music room has a light linoleum floor, walls of plastered or exposed concrete, wooden door and window frames. The double height ceiling space is clad in square acoustic panels, while the wooden structure of the mezzanine becomes the cover for the living room. Upstairs, both the floor and the handrails are made of cypress, the ceilings are finished in plaster, and the doors clad in fabric. In the entrance area, the hung ceiling is built of plastered wooden strips, a building method that was popular in the USA until the 50s and a clear reference to Yoshimura’s time there.

It is exactly this melding of traditional construction methods with an outlook towards the modernity that was entering both the psyche and the lifestyle needs of the Japanese population at the end of WW2 that made Yoshimura’s projects the subject of studies and teaching in architecture schools during the 60s.

Yoshimura was born in 1908 and died in 1997; ninety years that cut across the most important events of political, economic and cultural life in 20th century Japan.

The years of his youth and professional training, before the outbreak of WW2, are the years in which the “cultural contamination” between East and West changes direction. While at the beginning of the 1900s there was a strong and lively influence of Japanese and Chinese art on the West, in the 1920’s this trend reversed course, with Western styles and social trends infiltrating Japanese culture, design and lifestyle. Some Japanese cultural critics at the time likened this to a degenerative disease that was causing internal conflicts. Japan’s great novelist and essayist, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1886-1965) poses the emblematic question in “In Praise Of Shadows” (1933): “[…] one thing I fail to comprehend: why are we giving up and renouncing all of our customs? why are we abandoning our tastes? why are we not attempting to reconcile the new with our sensibilities?”.

Yoshimura lived the intense friction between the worlds of light and shadows during his formative years: he managed to overcome this dissonance by making his architecture the place where tradition and renewal come together, making the aspirations of young Japanese people concrete without renouncing their culture and their nature. This ability to synthesize Japanese and Western elements was evident even as a secondary school student. Later in life he recalled the feeling of entering Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel for the first time, shortly after the 1923 earthquake: “It was the first time that I felt emotional when faced with architecture. I said to my myself, this really shows the power of space. I felt that architecture was something extraordinary. It’s certainly the main reason I became an architect.” —Yoshimoro (cited by Gloaguen)

Yoshimura began his collaboration in design in the Tokyo office Czech architect of Antonin Raymond first part time as a student beginning in 1928 and then full time in 1931, immediately after his graduation from the Architecture Department of Tokyo Arts College (today Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music). Working with and for Raymond proved to be a transformative experience for Yoshimura. Raymond, an early admirer of Wright’s, represented a hybrid of different design cultures. After his graduation from the Czech Polytechnic Institute in Prague in 1910, Raymond had moved to New York, where he started his career in the office of Cass Gilbert, an early proponent of skyscrapers. There, Raymond was introduced to the use of reinforced concrete (Woolworth Building facades). He subsequently moved to Taliesin East to start his work experience with Frank Lloyd Wright, who took Raymond to Tokyo to work on Wright’s Imperial Hotel project. It is in the teachings of Wright and through the encounter with Japanese culture that Antonin Raymond absorbed the meaning of a modernism that characterized his work from then on, and infiltrated the thought and design process of his young assistant Yoshimura. Their collaboration lasted a decade and profoundly marked the young Yoshimura. The result was a perfect balance between traditional Japanese construction methods and the canons of modern Western composition.

Yoshimura’s first direct encounter with the West and its culture began in May 1940, when he accompanied Raymond to his design studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania, on the banks of the Delaware River. Yoshimura spent 18 months in this quiet town, with its typical American main street and traditional typology of the American cottage. This gentle experience allowed Yoshimura to glide towards a new vision of the world and of life in general – more unpredictable than his life in Japan, but devoid of trauma, and completely positioned within American culture. In his autobiography, Raymond (1973) praised Yoshimura for his “considerable contribution to the design of all the buildings in our office, and, what was most sympathetic to me was his knowledge of and interest in Japanese arts and architecture.” (p. 147)

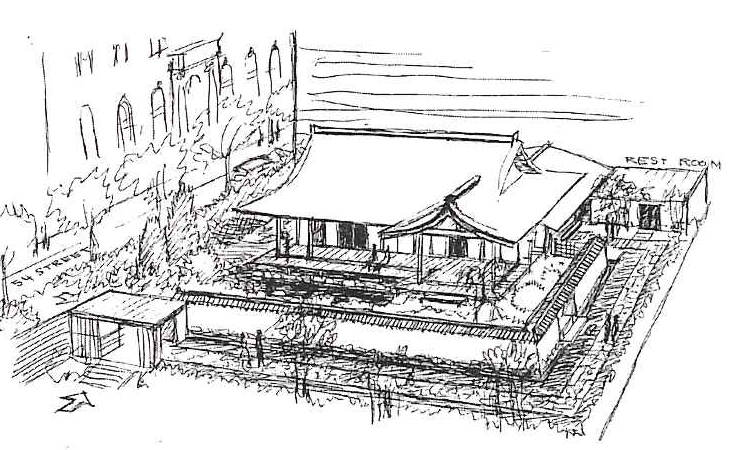

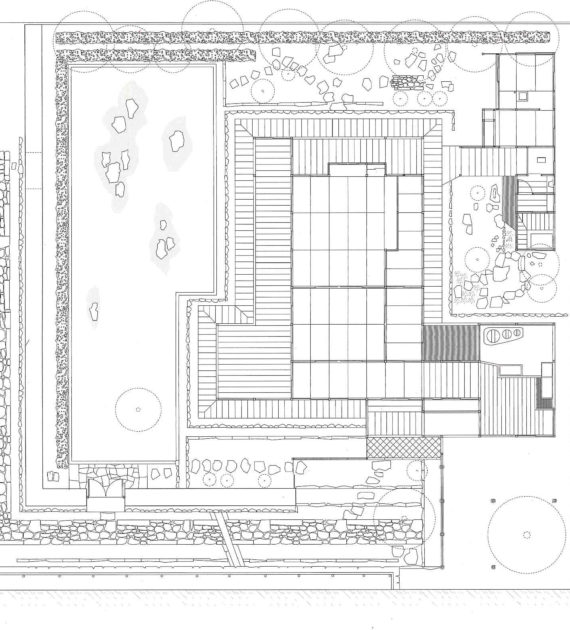

Shofu-So, The Japanese House and Garden, New York, 1954

Arthur Drexler, at the time curator of architecture and design at MoMA, hired Yoshimura to design this pavilion for the third edition of the “House in the Garden” Biennial, which exhibited “modern” residences to educate to a new way of living.

His profound knowledge of traditional Japanese architecture with its abundance of construction details, simplified for the purpose of this project, allowed Yoshimura an unexpected dialogue with both the exuberant curtain walls of surrounding high-rise buildings and the limiting demands imposed by the exhibition. The square area allotted to the pavilion is reminiscent of the garden at the Imperial Villa in Katsura in its subdivision and relationship to water, as well as in the modulation of the facades and the spatial continuity which makes the complex an integral part of the whole.

Drawing on his deep understanding of Japanese design, Yoshimura was able to meld the traditions of his own culture with Western rationalism, cross-referencing and exchanging architectural elements and ideas—always avoiding formalism, always keeping people, their lives and well-being as the generative and ultimate goals.

Although in his practice Yoshimura designed buildings also at the urban scale, the main focus of his activity was private dwellings, of which he designed and built more than 150.

“As an architect, however, I am glad when I have completed a building and can see people having a good life inside. To walk past a single house at twilight, with bright lights shining inside the house, being able to sense that the family enjoys their daily life; isn’t that the rewarding moment for an architect?”

As an architect, however, I am glad when I have completed a building and can see people having a good life inside.

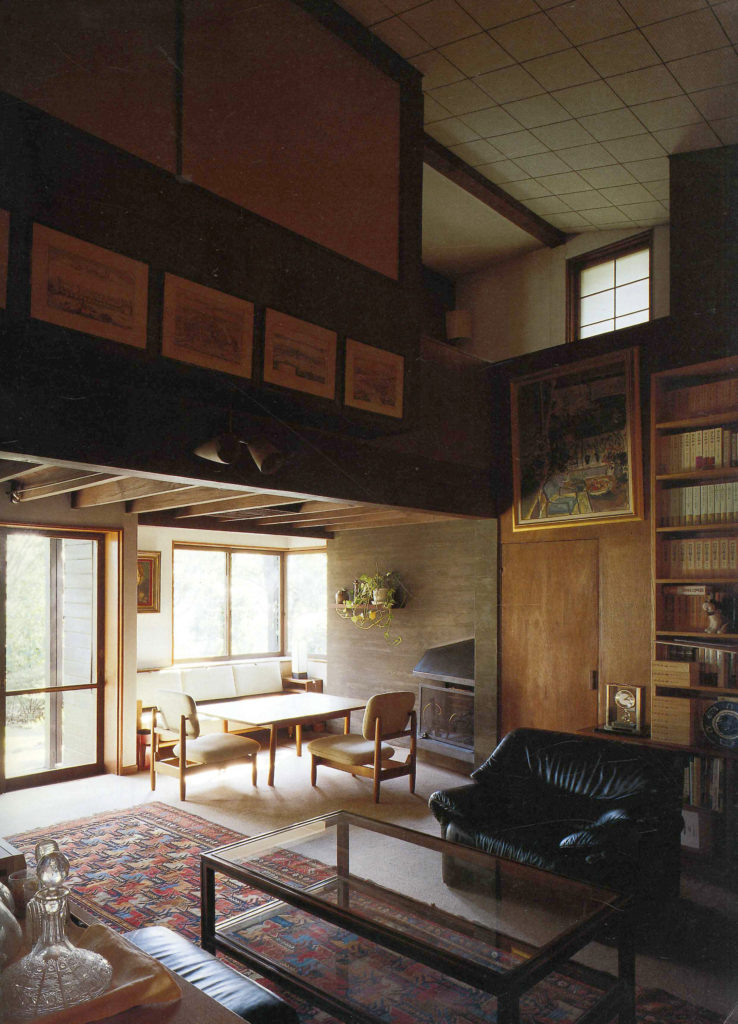

House at Inokashira, Mitaka, Tokyo 1970

Positioned at the edge of a trapezoidal lot of approximately 220 sq m (2,370 sq ft), this residence is developed over two levels of 87,5 sq m (940 sq ft). On the ground floor, a two-step high platform hugs the wall and breaks the rigor of the rectangular layout, inviting one to enter. Inside, the sequence of spatially dynamic rooms shows off Yoshimura’s compositive vocabulary of changes in elevation and double height volumes. The combination of materials – wall to wall carpet for the floors, plywood for the ceiling and painted plaster for the walls – underlines the shoji’s light filtering effect and makes the centripetal force of the central volume tangible, highlighting the central role of the inhabitant.

His profound knowledge of traditional Japanese architecture with its abundance of construction details, simplified for the purpose of this project, allowed Yoshimura an unexpected dialogue with both the exuberant curtain walls of surrounding high-rise buildings and the limiting demands imposed by the exhibition. The square area allotted to the pavilion is reminiscent of the garden at the Imperial Villa in Katsura in its subdivision and relationship to water, as well as in the modulation of the facades and the spatial continuity which makes the complex an integral part of the whole.

Drawing on his deep understanding of Japanese design, Yoshimura was able to meld the traditions of his own culture with Western rationalism, cross-referencing and exchanging architectural elements and ideas—always avoiding formalism, always keeping people, their lives and well-being as the generative and ultimate goals.

Although in his practice Yoshimura designed buildings also at the urban scale, the main focus of his activity was private dwellings, of which he designed and built more than 150.

“As an architect, however, I am glad when I have completed a building and can see people having a good life inside. To walk past a single house at twilight, with bright lights shining inside the house, being able to sense that the family enjoys their daily life; isn’t that the rewarding moment for an architect?”

Residential projects are where Yoshimura develops his principles for composition, continuously looking for an ideal prototype to satisfy both practical daily needs as well as the pleasure of living in a space: the hierarchy of spaces and their relationship with the inhabitants, construction methods, the perfecting of details, the relationship between man and nature. These principles are effortlessly translated into larger buildings and complexes at the urban scale as well.

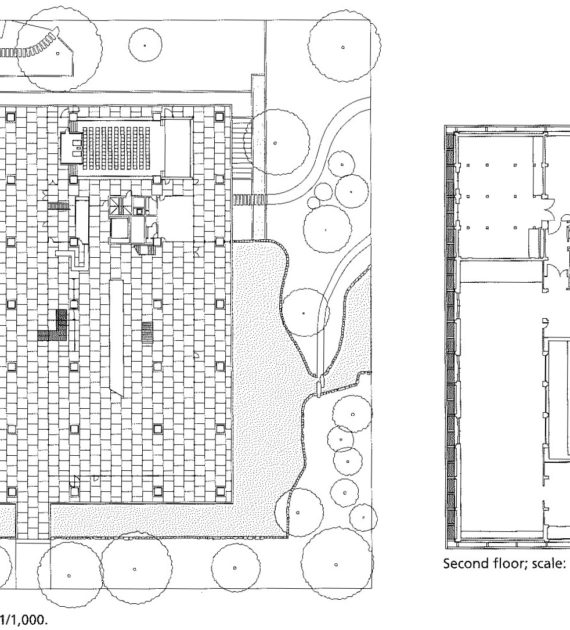

Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts (Lecture Building), Nagakute, Aichi 1966-1974

The change of scale between small dwellings and larger buildings does not affect Yoshimura’s founding principles and his thought process.

The ambience of the site, that’s the starting point through which you should perceive the entirety.

The ambience of the site, that’s the starting point through which you should perceive the entirety. Next, you look at things like the light from the sun and the paths of the wind. After that, you look at the [site’s] relationship with the arrangement of surrounding roads. Having done all that, a shape will naturally emerge.

A change in vocabulary is particularly evident in this project for a hilltop building on the outskirts of Nagoya. The imposing wedge shaped reinforced concrete column and the characteristic brise soleil define a structure that represents a clear demarcation line between human intervention and the surrounding nature, while the ample glazed surfaces and the connecting staircases maintain a dialogue between the parts. The static nature of the design becomes more animated in the interior, where a sequence of spaces seamlessly flows into each other, enabling a fluid, functional use.

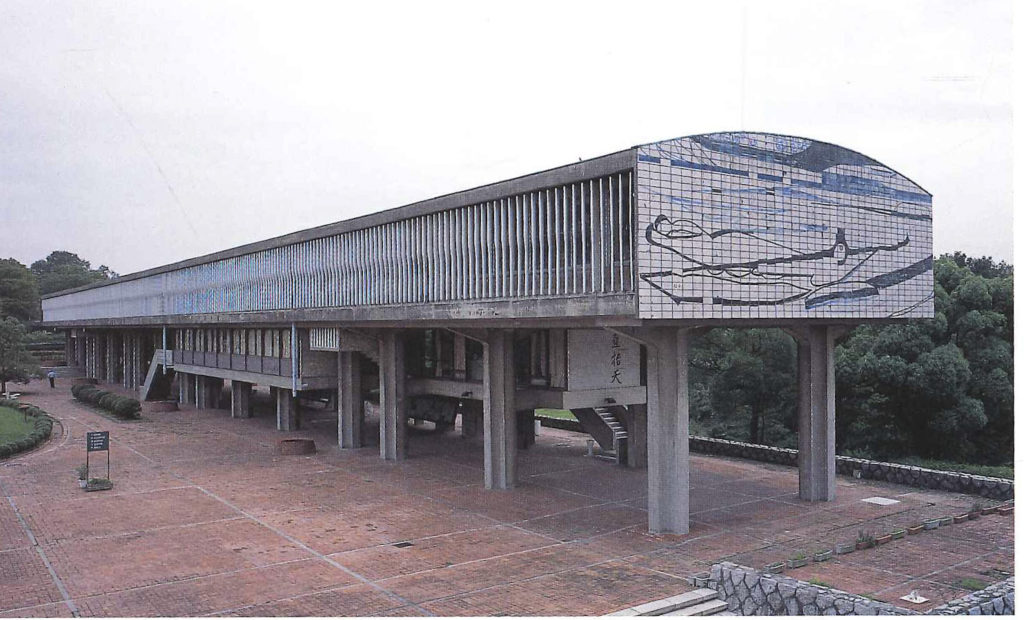

Nara National Museum, Nara, Nara, 1972

This project is an expansion of the Buddhist Art Museum inside Nara Park. Contrasting the typical stylistic elements of Western architecture of the 1800s, which had been adopted by arch. Tokuma Katayama for the original building, Yoshimura returns to the canons of historic Japanese architecture, remodeling them for the construction techniques of reinforced concrete.

The pilotis taper towards the top and anchor the building to the surrounding soil, characteristic of Yoshimura’s rapport with nature. The interconnected spaces maintain the human presence at their core and interpret elements of Eastern tradition into an open plan layout.

A single house that I design will transform the streetscape. You want to feel that way, or nothing good will result. I think architects have a social obligation.

The architect’s social responsibility will be the real narrative that establishes the logical relationship between cause and effect, for built and unbuilt projects, at every scale.

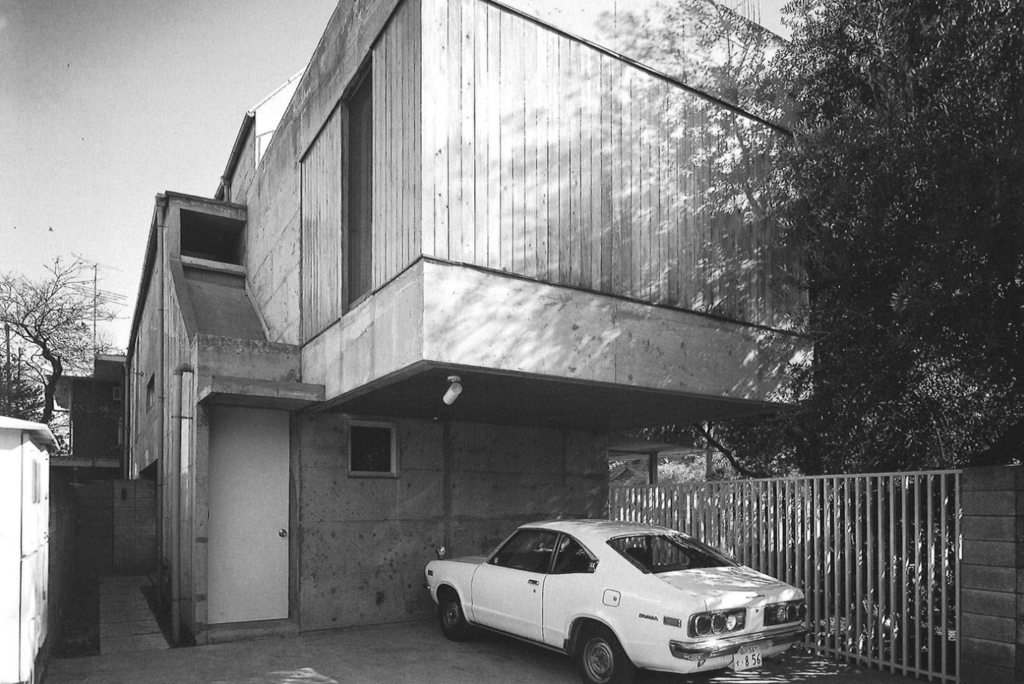

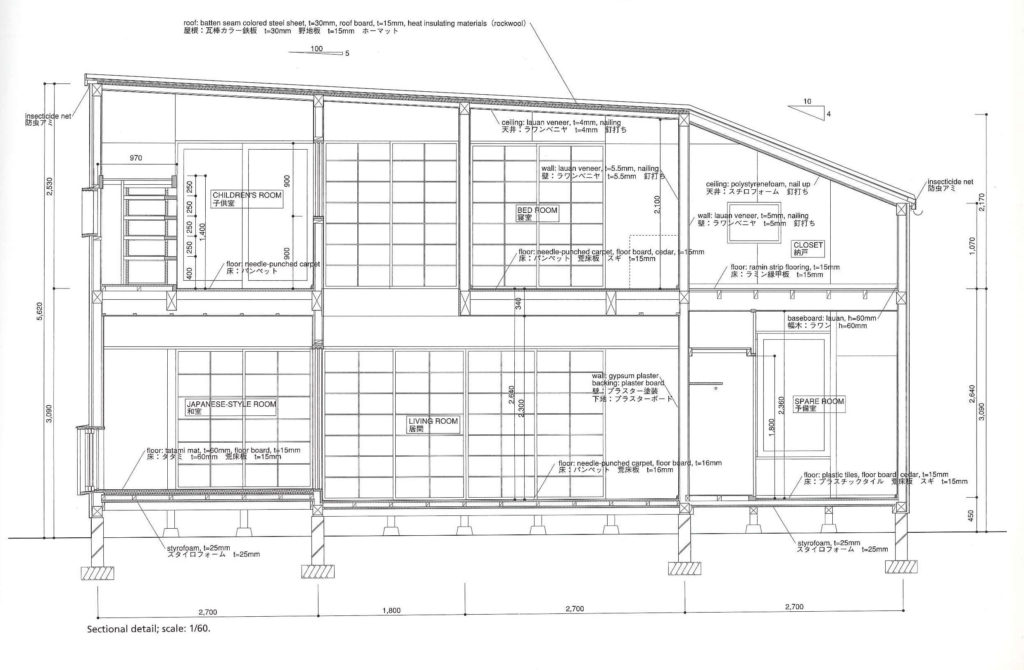

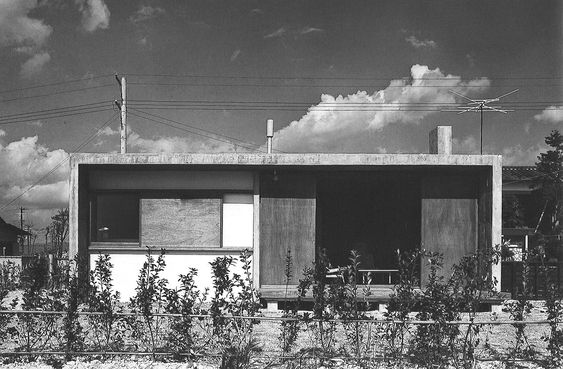

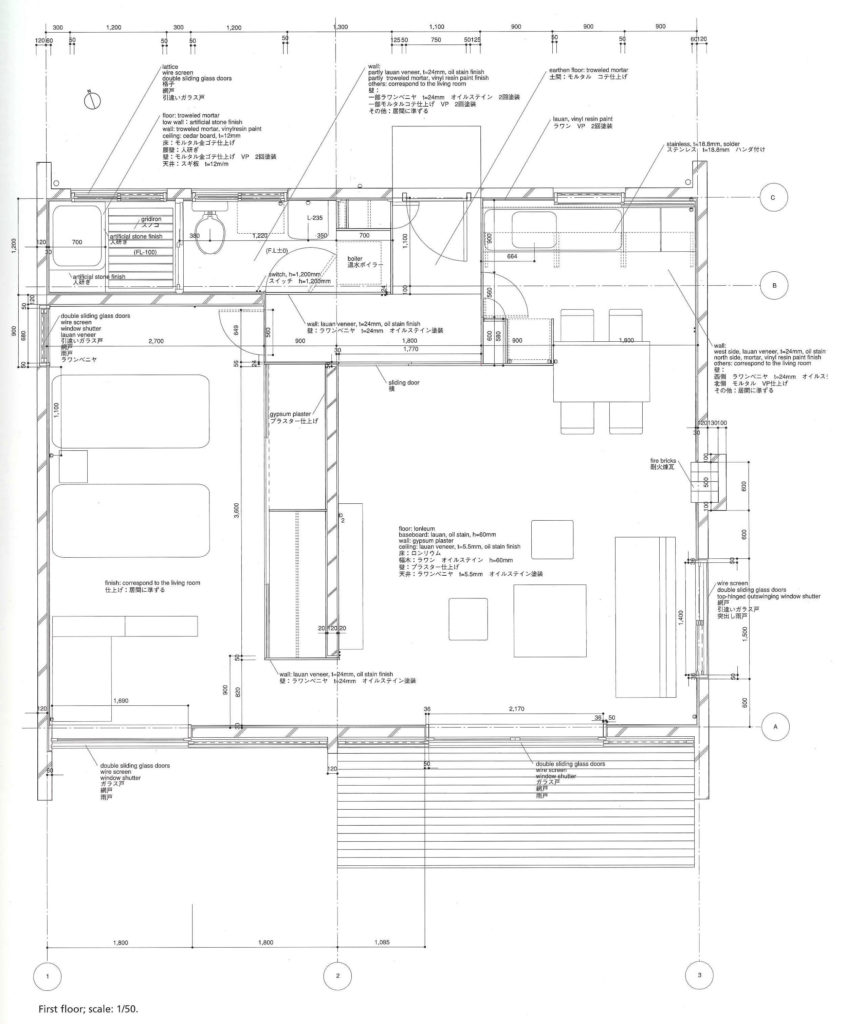

House at Ogurayama, Uji, Tokyo, 1966-71

This small house contains modernist Western influences and traditional Japanese layout schemes. The rational character of structure, materials and dimensions in this low-cost construction all exemplify the research that Yoshimura dedicated throughout his career to the study of a prototypical residential model. As an alternative to the more expensive wooden post and beam construction, walls are made of prefabricated reinforced concrete panels. The walls’ finish alternates between plaster and mahogany from the Philippines (lauan), both inside and outside. The internal spaces are arranged around a central hall and extend towards the garden through openings with sliding doors.

The reference to the shoin style becomes therefore a constant in the layout: a large internal space, made into the intimate core by the surrounding corridors and the smaller spaces that are separated by shoji (the typical entrances of high-ranking military’s dwellings or the dedicated study rooms in monasteries) becomes the focal point of distribution, the center of gravity which determines everything else.

If a house has a center of gravity, first of all there is stability. From stability there is serenity. I think this leads to a pleasant feeling.

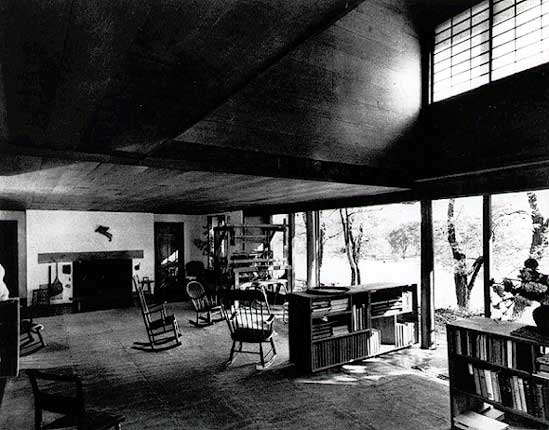

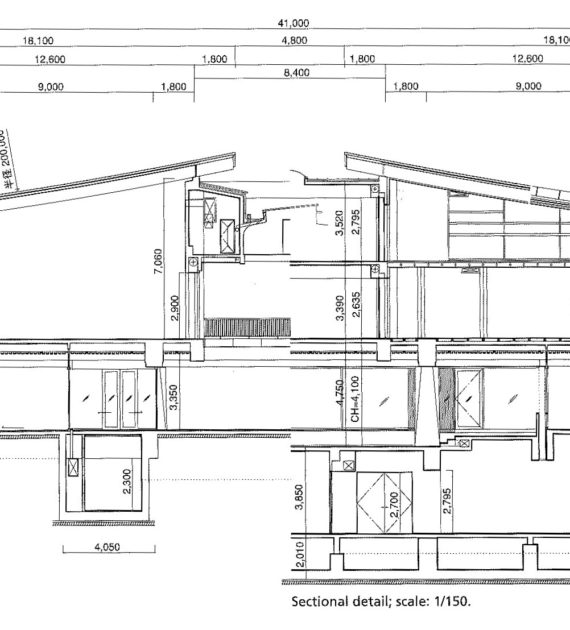

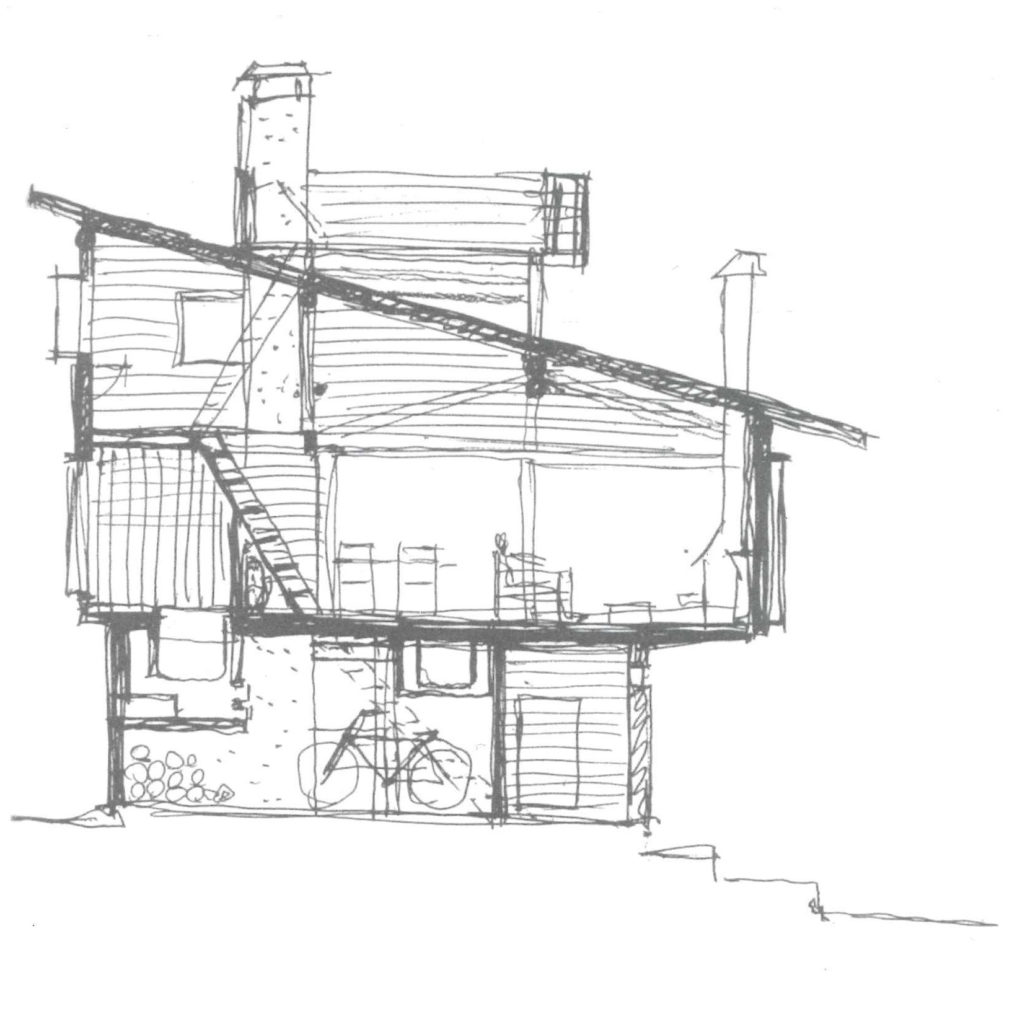

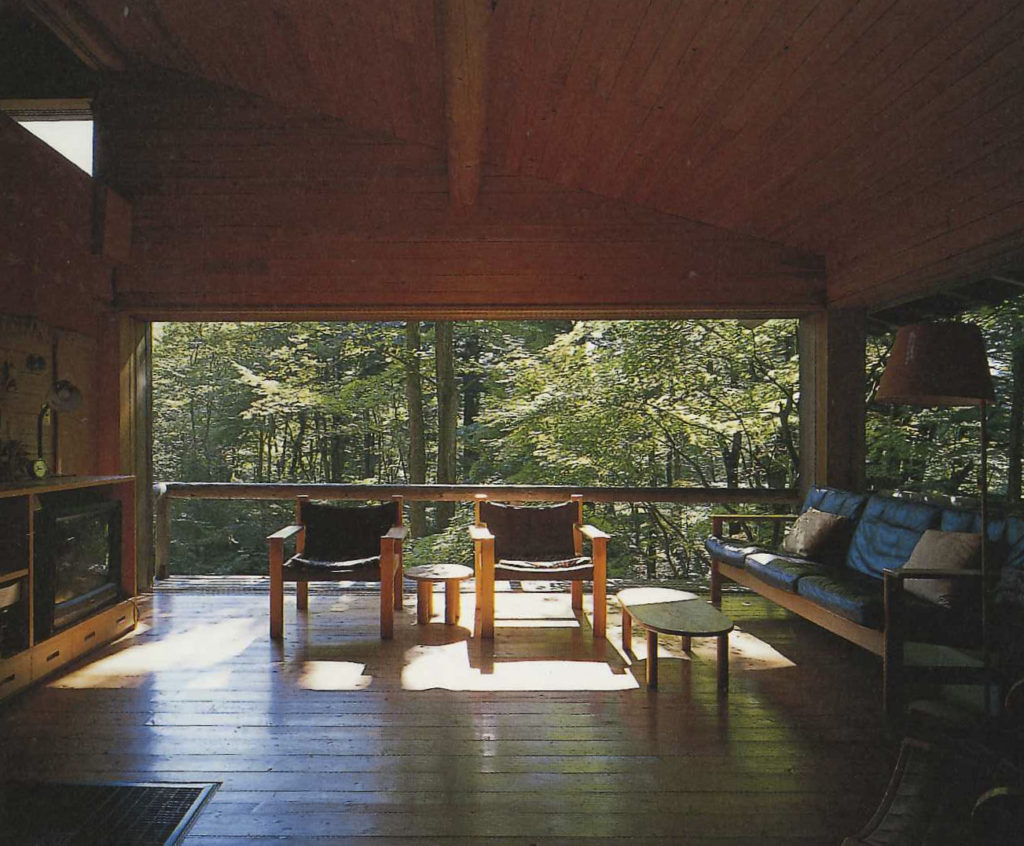

Mountain Lodge A, Karuizawa, Nagano, 1963

Yoshimura built this project inside a wooded area for his own family, and it is the first built example resulting from the studies dedicated to a residential typology in wood, anchored to a reinforced concrete slab and with a single plain inclined roof.

The house is developed over four floors based on the distributive principles of the shoin style. The concrete platform which contains the technical systems, expands outside into the slightly sloped terrain of the forest with a wooden terrace; the cedar staircase leads to the first level, opening onto the large central space which connects the accessory spaces, and continues to the mezzanine with the study area and onto the roof terrace. The cedar plank wall cladding, cypress floors, the wooden structure of the roof and the large glazed surfaces define a seamless continuity between interior and exterior, reinforcing the symbiotic relationship between man and nature, characteristic of Japanese philosophy.

A non-static spatial gravitas is created through changes in elevation that are cut into the double height volumes simply offsetting floors or ceilings; by the everchanging infiltration of nature through the fragile barriers of the large glass surfaces, by the opalescent light filtered through shojis or the light reflecting on the water that surrounds the building.

A kinematic is amplified by the visual interaction between man and objects; one’s glance bounces through the space in unexpected ways, guided by the continuous exchange between light and shadow, surrounded by that “arcane luminescence” which, according to Tanizaki, leads one to forget the passing of time and defines the character of the Japanese room.

«The starting point of a house is a cube»: Yoshimura makes inspired use of this reference to pure geometry as the original form (a hommage to the European Masters) by carefully fragmenting the internal volumes and subsequently dilating the small spaces of his houses through controlled flashes of natural light; with a clean sense of composition and the use of clear elements that have their own strong identity he manages to determine the autonomous character of his constructions within nature; they become part of it while remaining distinct, exalting that sense of intimate harmony – mono no aware – which is intrinsic part of the Japanese spirit; possibly corresponding to our Western understanding of the noble simplicity and quiet grandeur of classicism.

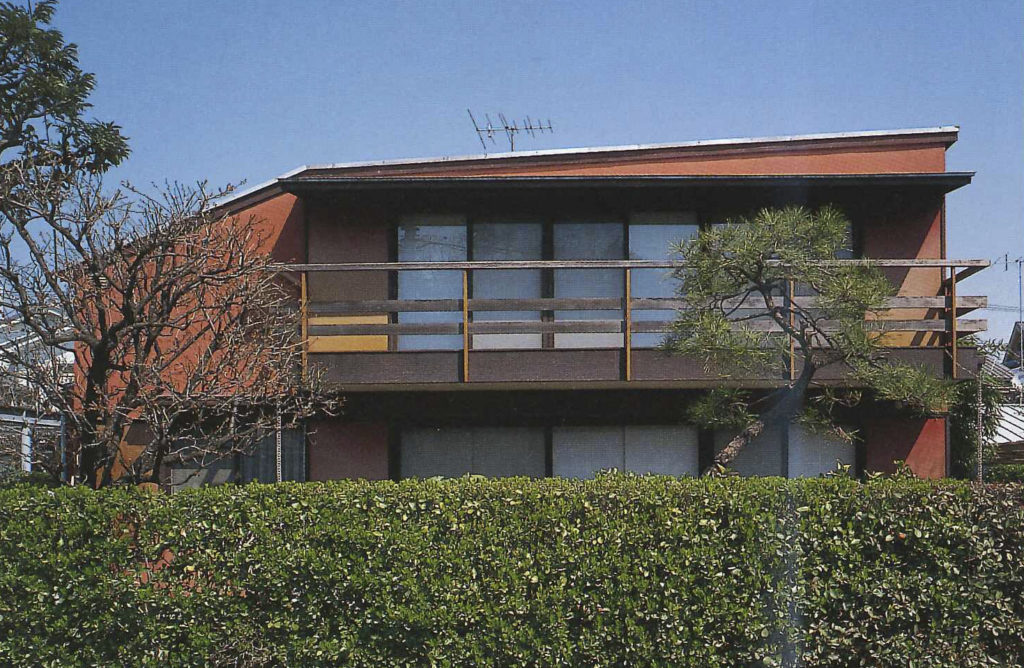

House at Minami-dai, Nakano, Tokyo 1957

Yoshimura builds his own home through subsequent additions. Located on a trapeziodal lot in the residential neighborhood of Nakano, the house creates a symbiotic relationship with the traditionally designed garden. The reference to the shoin style sets the entrance at the center of the residence, therefore eliminating the need for corridors and allowing for a seamless flow of spaces. The large openings with sliding screens, the changing ceiling heights of spaces, the texture of materials and furnishings, which have been designed by Yoshimura himself, all contribute to amplifying the modulation of light intensity. The large shojis of the far living room window expand the surface with a distinctive trait of Yoshimura’s style. Beyond the glazed surface the narrow wooden terrace becomes the connecting element to the garden; an explicit reference to the contemplation of nature as narrated by Prince Genji.

Biography

1908 born in Midori-machi, Honjo Ward, Tokyo

1931 Graduated from the Architecture Department of the Tokyo Arts College (Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music)

1931-1941 Employed in the office of Antonin Raymond, Architects and Associates

1941 Established his own architectural office

1945-49 Appointed assistant professor at the Tokyo Arts College, Architecture Department of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music

1962 Appointed full professor in the Architecture Department of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music

1970 Appointed professor emeritus of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music

1991 Member of the Japan Academy of Arts

1997 Dies in Nakano (Tokyo)

Awards

1956

Awarded the Japan Institute of Architects prize for International House

Awarded the Parsons prize for a series of buildings in the United States of America

1975

Awarded the prize of the Japan Academy of Arts for the Nara Prefectural Museum

1982

Awarded the 3rd orders of the Rising Sun

1989

Awarded Mainichi Art award for the Hall of Chamber Music, Yatsugatake

1995

Recognized the Person of Cultural Merit

1997

Awarded the 2nd order of the Sacred Treasure

Works

1945

Hepborn Memorial, Yamashita-co, Yokohama

1947

Silk Fair (Tokyo Shirokiya Departmente Store)

1953

House at Yoyogi,Shibuya, Tokyo

House at Shimousa-Nakayama, Ichkawa, Chiba

Sakura Sanitarium, Sakura, Chiba

1954

Shofu-so (The Japanese House and Garden), New York

1955

House at Jiyugaoka, Meguro, Tokyo

International House and Residences, Minato, Tokyo

1956

New York Offices of Japan Airlines, New York City

Motel on the Mountain, Suffern, New York

1957 House at Minami-dai, Nakano, Tokyo

Seaside Lodge at Hayama, Kanagawa

1958 House at Sendagaya, Shibuya, Tokyo

New York Takashimaya Department Store, New York City

Fugetsudo Coffee shop and Restaurant, Ueno, Tokyo

1959 House at Ogikubo, Suginami, Tokyo

Hotel Kowakien, Kowakidani, Hakone

Kawasho, Hakata, Fuguoka

1960 Kujusan Mountain Lodge, Oita

1961 House at Aoyama, Shibuya, Tokyo

Sony Research Laboratories,Hodogaya, Yokohama

1962 Amherst Hall, Doshisha University, Kyoto

Building for National Cash Register, Minato, Tokyo

1963 Mountain Lodge A, Kuruizawa, Nagano

Yokota Dental Clinic Ginza, Tokyo

1964 Hakoneyama Apartments, Kowakidani, Hakone

Tokyo Club, Kasumigaseki, Tokyo

1965 House at Ikedayama, Shinagawa, Tokyo

House at Hamadayama, Suginami, Tokyo

Tawaraya Inn, Kyoto

House at Shonan, Akiya, Kanagawa

Solfege School, Toshima, Tokyo

1966 House at Kugayama, Suginami, Tokyo

Lecture Building, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

House at Ogurayama, Uji, Tokyo

Monjuso Inn, Kyoto

Osaka America Building, Osaka

1967 House at Chigasaki, Chigasaki, Kanagawa

Student Center, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

1968 The Imperial Palace (prelimuinary design), Chiyoda, Tokyo

Library and Archives, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

1969 Namekawa Island Lodgings/ Katsuura, Chiba

House at Kogaicho, Minato, Tokyo

Aoyama Tower Building and Hall, Minato, Tokyo

Namekawa Island Restaurant, Katsuura, Chiba

Concert Hall, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

Administration Building, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

1970 Mountain Lodge B, Karuizawa, Nagano

Mountain Lodge A at Lake Yamanaka, Yamanaka, Nagano

House at Inokassura, Mitaka, Tokyo

Hotel Fujita, Kyoto

Shin-sanya Lodge and Study Center for the Shin-Nittetsu, Shibuya, Tokyo

Graphic and Plastic Arts Dept., Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

Music Dept., Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

Gymnasium and Club, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

1971 House A at Den’en-chofu, Ota, Tokyo

House at Takagicho, Minato, Tokyo

Japan House, New York

Memorial to War Dead Who Perished at Sea, Kannonzaki, Kanagawa

Faculty Club and Sculpture Studio, Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts, Aichi

1972 Takano Pearl Company (Kudan Grand Hotel), Chiyoda, Tokyo

Nara National Museum, Noboroioji, Nara

1973 Mountain Lodge C, Kuruizawa, Nagano

Mountain Lodge D, Kuruizawa, Nagano

1974 Residence at Pocantico Hills, New York

Mountain Lodge B, Yamanaka, Yamanaski

Mountain Lodge at Atami Nature Village, Atami Shizuoka

House at Tateshina, Chino, Nagano

Taishoya Inn, Saga

YCA Building at Yamawaki Art Academy, Chiyoda, Tokyo

Sankeido gallery, Chuo, Tokyo

1975 Mountain Lodge C, Yamanaka, Nagano

Kiso Country Club, Kisokaida, Nagano

1976 House B ad Den’en-chofu, Ota, Tokyo

House at Nishiyama, Sakyo, Kyoto

House at Izu Taga, Atami, Shizuoka

1977 Atami Apartments, Atami, Shizuoka

House at Yutenji, Meguro, Tokyo

Royal Norwegian Embassy in Tokyo, Minato, Tokyo

1978 Meguro House, Meguro, Tokyo

Tamagawa Hospital, Setagaya, Tokyo

1979 House at Yakumo, Meguro, Tokyo

House at Toritsu Daigaku, Meguro, Tokyo

House at Seijo Gakuen, Setagaya, Tokyo

House A, Karuizawa, Nagano

House B, Karuizawa, Nagano

Kawanakajima Country Club, Clubhouse, Nagano

1980 House C, Karuizawa, Nagano

Monjuso Inn, Miyatsu, Tokyo

Karuizawa Green House, Karuizawa, Nagano

House at Takamatsu, Mure, Kagawa

House at Tateshina, Chino, Nagano

House at Karatsu, Karatsu, saga

House A at Kamikitazawa, Setagaya, Tokyo

Hikawa Hillside, Minato, Tokyo

Restaurant Carnival, Takamatsu, Kagawa

1981 House at Asagaya, Sugunami, Tokyo

House at Soshigaya, Setagaya, Tokyo

House at Izu-kogen, Ito, Shizuoka

Four Season, Japan Total Club, Ashinoko Lake Annex, Hakone, kanagawa

1982 House at Oyamadai, Setagaya, Tokyo

Tamagawa Hospital, Setagaya, Tokyo

Miyagawa Eel Restaurant, Tsukiji Main Branch, Chuo, Tokyo

1983 House at Den’en-chofu, Ota, Tokyo

House B at Kami-kitazawa, Setagaya, Tokyo

House D, Karuizawa, Nagano

House at Kumagaya, Kumagaya, Saitama

Cunningham Harmony House, Karuizawa, Nagano

Raymond Building, Setagaya, Tokyo

1985 House E, Kuruizawa, Nagano

House at Toyohashi, Toyohashi, Aichi

Nagano Head Office of Kitano Construction Corporation, Nagano, Nagano

Monjuso Inn, Miyazu, Kyoto

Matsuishi Building, Shibuya, Tokyo

1986 House at Shimo-ochiai, Shinjuku, Tokyo

Intervoice Karuizawa House, Karuizawa, Nagano

Villa Miho of Shinji Shumei Association/ Shigaraki, Shiga

Hotel Japan Shimoda, Shimoda, Shzuoka

1987 House F, Karuizawa, Nagano

1988 House at Yuigahama, Kamakura, Kanagawa

The Hall of Chamber Music, Yatsugatake, Minamimaki, Nagano

1989 House at Yatsugatake, Minamimaki, Nagano

1990 Sosei Country Club, Clubhouse, Narita, Chiba

House G, Karuizawa, Karuizawa, Nagano

1991 The Art Museum of the Kato, Gifu, Gifu

Kawana Club, Ito, Shizuoka

Kasatsu Concert Hall, Kasatsu, Gunma

1992 Suzunoki Ebisu Building, Shibuya, Tokyo

House at Kamiuma, Setagaya, Tokyo

1993 Miho Golf Club, Miho, Ibaragi

1994 Kitano Constyruction Corporation Tokyo Head Office Building, Chuo, Tokyo

Tea House Kaigetsu, Chinzai, Saga

Nikko Kirifuri Country Club, Nikko, Tochigi

1995 House at Takanawadai, Shinagawa, Tokyo

1996 House at Nakameguro, Meguro, Tokyo

Matsunaga Lady’s Clinic, Shimizu, Shizuoka

Kurashiki Sakuyo University, Kurashiki, Okayama

1997 Nara National Museum East Wing, Lower level Lounge, Nara, Nara

Techinical Museum, Setagaya, Tokyo

Jukoin-Ito-Betsuin, Ito, Shizuoka

References:

Itoh, Teiji (1972). The Classic Tradition in Japanese Architecture — Modern Versions of the Sukiya Style. Weatherhill/Tankosha.

Young, David and Michiko (2007) The Art of Japanese Architecture, Tokyo ; Rutland, Vt. : Charles E Tuttle Co, c2007

Raymond, Antonin (1973), Antonin Raymond: An Autobiography, Rutland, VT: Tokyo, Japan

Charles E Tuttle Co.

Yoshimura, Junzo (1979) Junzo Yoshimura Collected Works, 1941-1978, cited by Yola Gloaguen (2016) Les villas réalisées par Antonin Raymond dans le Japon des années 1920 et 1930. PhD thesis (in press), page 190.

Author

Gioia Gattamorta is an architect living and practicing in Ravenna, Italy. Her projects range from new construction to architectural conservation. She has taught at the Architecture faculties of the universities of Florence, Venice and Bologna and at the New Jersey Science and Technology University. Sam Perkins is a New York based writer and board member of SilentMasters. For his full bio please see here.