Melchiorre Bega

1898 - 1976With their focus on clean line and use of space, Bega’s interiors challenged and disturbed established bourgeois design traditions.

From the intimate to the monumental, he was comfortable working at any scale.

“I always dreamt of building in steel, because steel for me has an emotional power.” – Melchiorre Bega

“The Galfa Tower reaches a beauty that is immediately understood and loved because it embodies the shape of a technical, esthetic and representative truth. — Gio Ponti

Melchiorre Bega, architect and designer, who was active between the 1930s and 60s, arguably did as much as many better-known designers to put his stamp on the urban and domestic world of design we inhabit today.

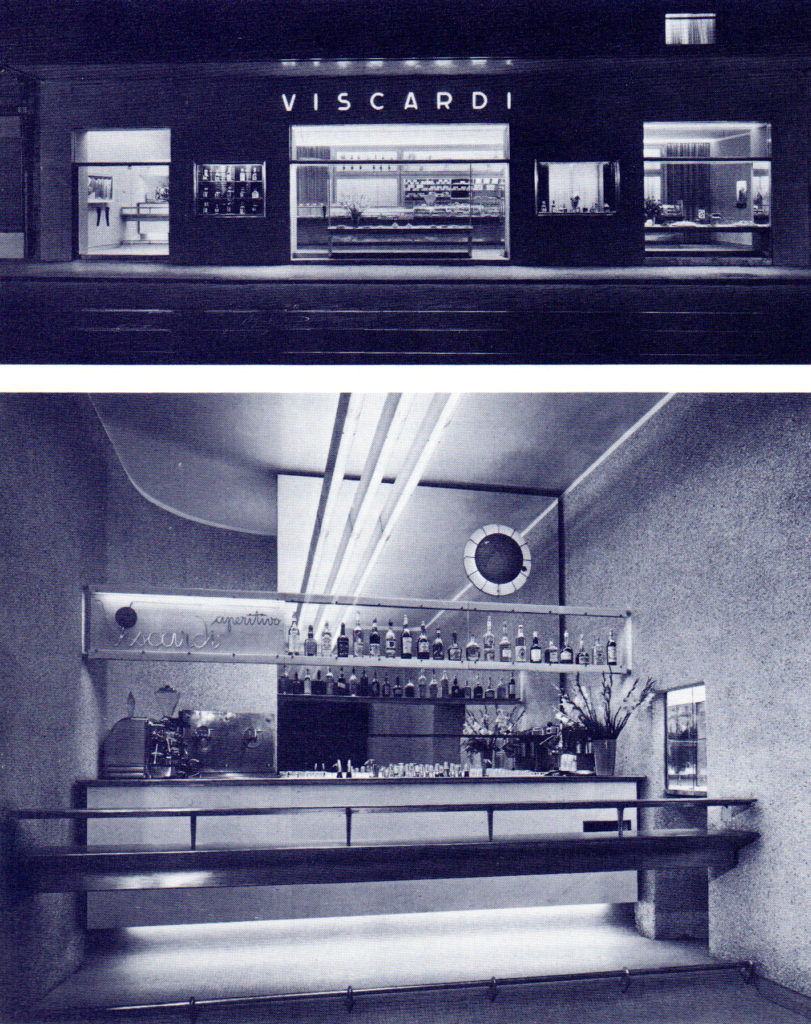

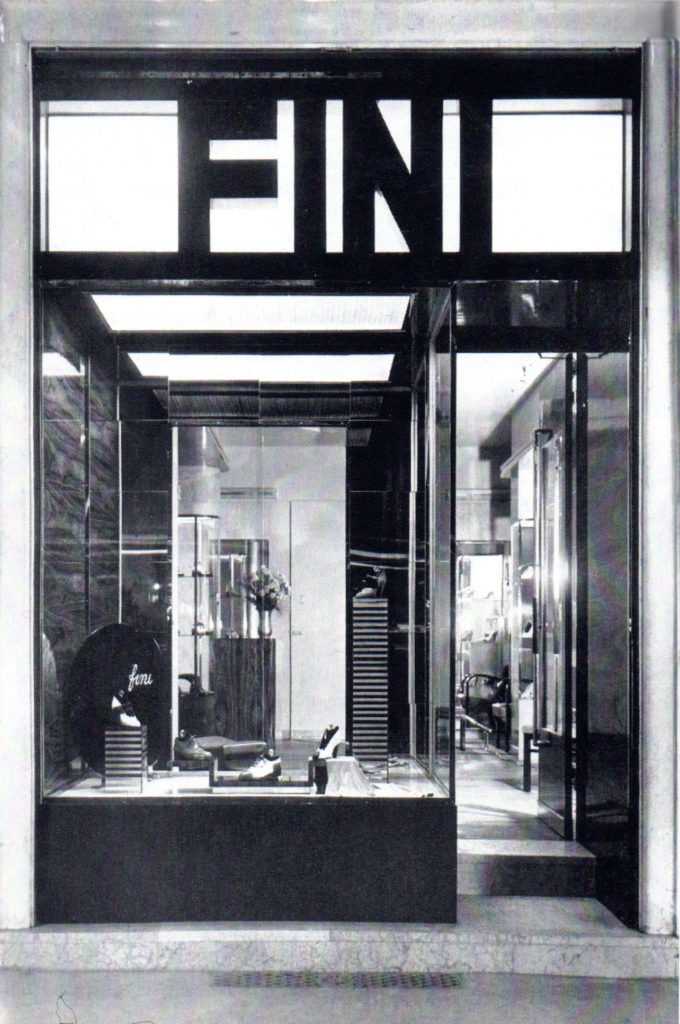

His vision seemed radical at the time. In the pages of the influential design magazine, Casabella, Bega was singled out by leading art critic Raffaelle Giolli for his ultramodern interiors, designed in a mix of “understated rationalism” and Novecento style. Rationalism and Novecento were among the fiercely debated new design theories in Italy in the decade following the First World War, and though the schools differed in approach, they expressed a desire to return to classic Italian forms, stripped of excess decoration typical of Art Deco or Art Nouveau1. With their focus on clean line and use of space, his interiors were freshly seductive and captivating, even as they challenged and disturbed established bourgeois design traditions.

His works include over 300 design projects in the major cities of Italy and abroad. In Milan and Bologna alone, Bega designed 40 retail stores, 8 hotels and 41 public buildings. His commissions abroad took him to Tripoli, Hamburg, Berlin, Paris, London, Geneva, Ankara and New York, where he oversaw the interior design of the Palazzo d’Italia in Rockefeller Center. He was comfortable working at any scale, from the intimate to the monumental2—product design, furniture, private homes and apartments, retail shops, cafés and bars, hotels and movie theaters, banks and office high-rises, churches and schools, yachts and cruise ships. And for most of these assignments, he also designed the furnishings and oversaw their manufacture.

Born into design.

Unfortunately, many of Bega’s most iconic interior designs, especially the retail stores and bars and cafés from 1920’s and 1930’s, have been lost to the constant urban renewal that all major cities undergo. Original pieces of his furniture are collectors’ items. His skyscrapers remain, honored and updated for current use, testaments to one of the most fertile, vibrant talents of the 20th century, known and appreciated by specialists but largely forgotten by the general public.

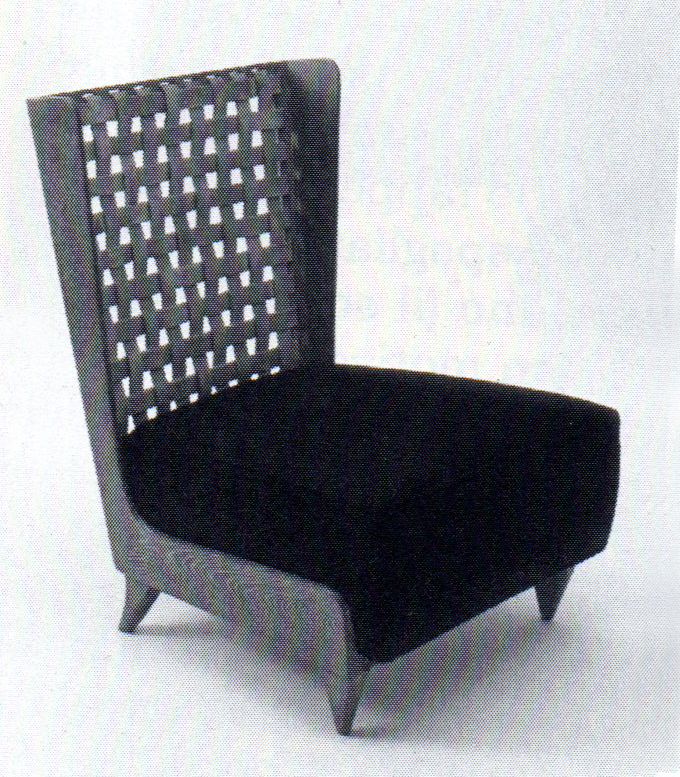

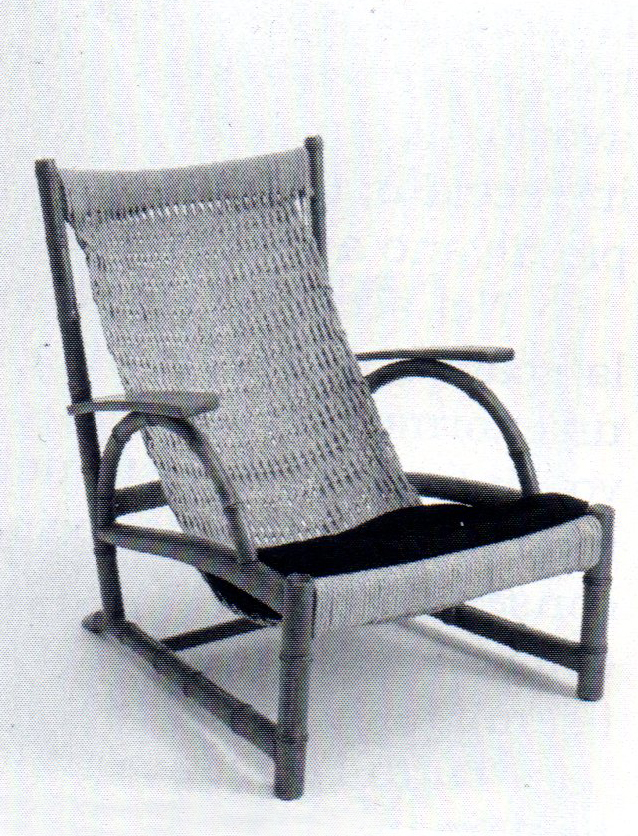

Melchiorre Bega was born in 1898 into a family of designers in Caselle di Crevalcore, twenty miles northwest of Bologna. The family company, Vittorio Bega & Figli in Bologna, specialized in the manufacture and restoration of fine furniture. The workforce of 250 included woodworkers, upholsterers, and finishers, as well as specialists in the intricate crafts of intarsia and intaglio. Along with his siblings Mario, Dante and Iole, Melchiorre was educated in the craftmanship tradition of the firm and went to work there full-time in 1919 after graduating from the Fine Arts Academy of Bologna. Among his first jobs was as a restorer of fine furniture. This connection to craftsmanship remained a constant throughout his career which ended with his death in 1976.

Bega himself divided his career into “Bega 1,” pre-World War Two, and “Bega 2,” after the war. Recalling his younger self, he later said, “Just before the beginning of the 1920s, Bega 1 emerged, the revolutionary decorator who was going to practically conquer public opinion.” 4

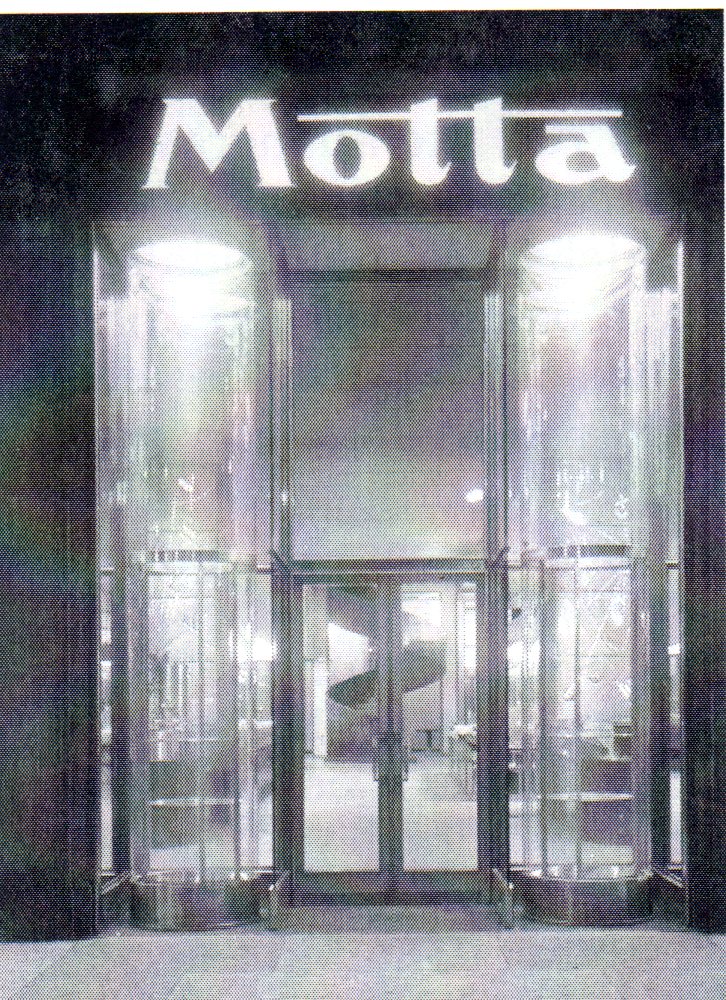

He quickly made a name for himself. Soon after arriving at V. Bega & Figli in 1919, Bega was designing the interiors for the most fashionable stores, bars and cafés of Milan, Bologna and Rome. He designed and, through V. Bega & Figli, saw to the construction of the furniture and furnishing. Bega’s stripped down, unfussy design vocabulary captured the modern, accelerated pace of life that followed World War One. He understood that shopping or going to a bar or café was an esthetic, self-affirming experience, not just a transaction. When customers entered a Motta café, a Perugina confectionery, the lobby of a Bega hotel or the Galtrucco fabric store—all of them Bega clients—they stepped into a total esthetic experience. Depending on the job, Bega designed the display windows, the shelving, counters, functional and ornamental fixtures, furnishings and furniture, controlling the entire customer experience.

His roster of clients grew to include the business and artistic elite of Milan and Bologna. Bega designed their stores, offices, places of business and private residences, such as those of journalist Enzo Biagi, Giovanni Buitoni, of the famous pasta company, and Commendatore Motta of café and pasticceria fame.

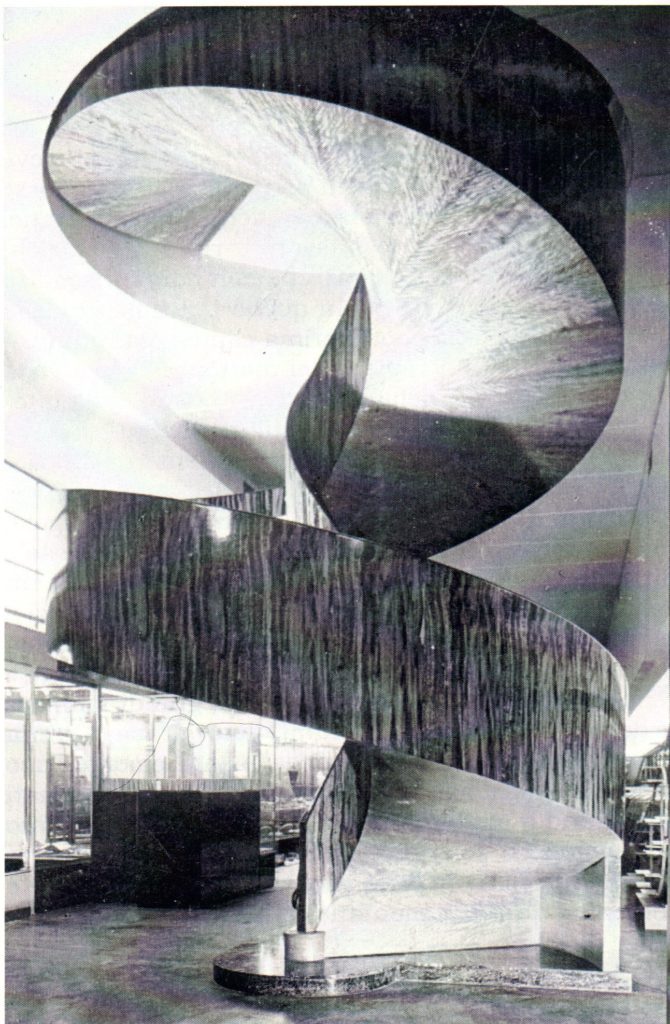

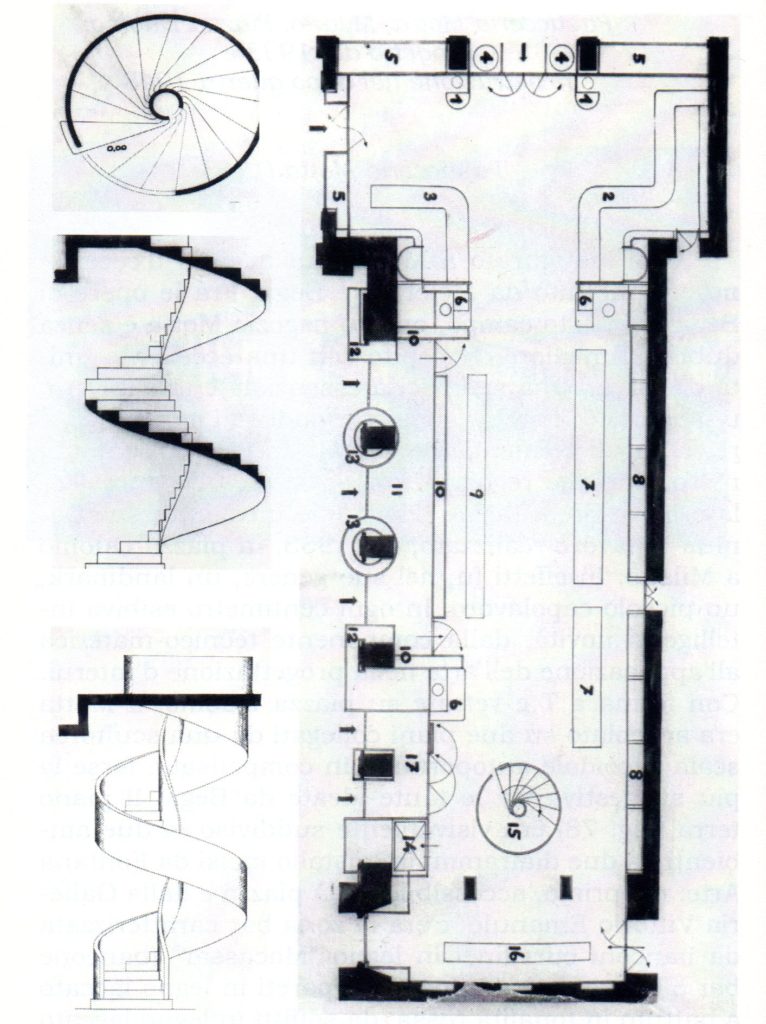

One of his signature creations from the mid-1920’s was an ingenious spiral staircase constructed using a plywood frame that could be adapted and reshaped to the individual specifications of each job. Unlike most spiral stairways, Bega’s did not require a central axis to provide strength. This allowed him to create elliptical curves that were arresting and flamboyant sculptural statements in addition to being cleanly functional. It reappears in a number of forms, including the Motta café he designed in 1928 that still stands on the Piazza del Duomo in Milan. (In 2014 the café was included in Lombardy’s “Register of Historic Places of Commerce”.)

Applying his principles to domestic architecture, Bega designed Casa Appenninica, in collaboration with A. Legnani and G. Ramponi, which was presented to the Milan Triennale design fair in 1933. The spare, elegant design mixed traditional and modern—ebony and burl walnut furniture with linoleum and concrete. In keeping with his total design concept, he included paintings by Santi and dal Monte, and sculptures by Pini. Beginning in the late 1920’s, owners of yachts, naval vessels and cruise ships began to seek him out to design their public rooms and cabins: his sumptuous yet spare kitting out of the luxury yacht, “Aurora” (1928), was featured in an issue of Domus. This was quickly followed by the 825-meter foot ocean liners, the “Bremen” (1929) and the “Conte di Savoia” (1931), and even a battle cruiser for the Italian navy, the “Zara” (1930).

In a review of the second volume of Bega’s designs from the 1920’s and 1930’s, Italy’s leading architect and design critic, Gio Ponti wrote: “This second volume of Melchiorre Bega’s work… documents today’s life in residential spaces, as well as demonstrating that stores and public venues are among Bega’s most admirable specialties.”3

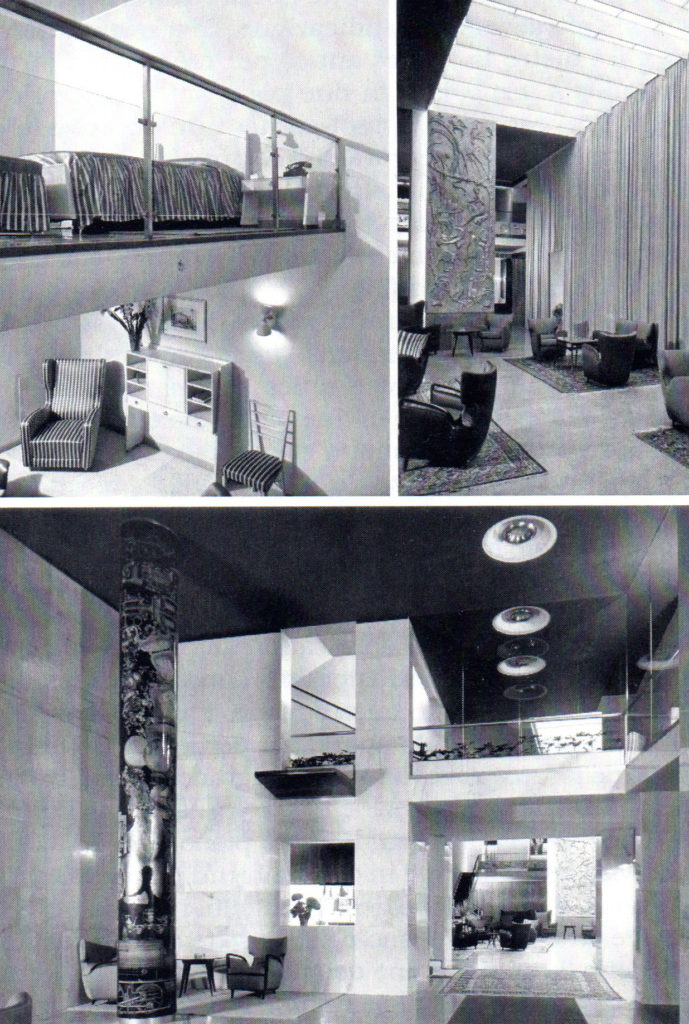

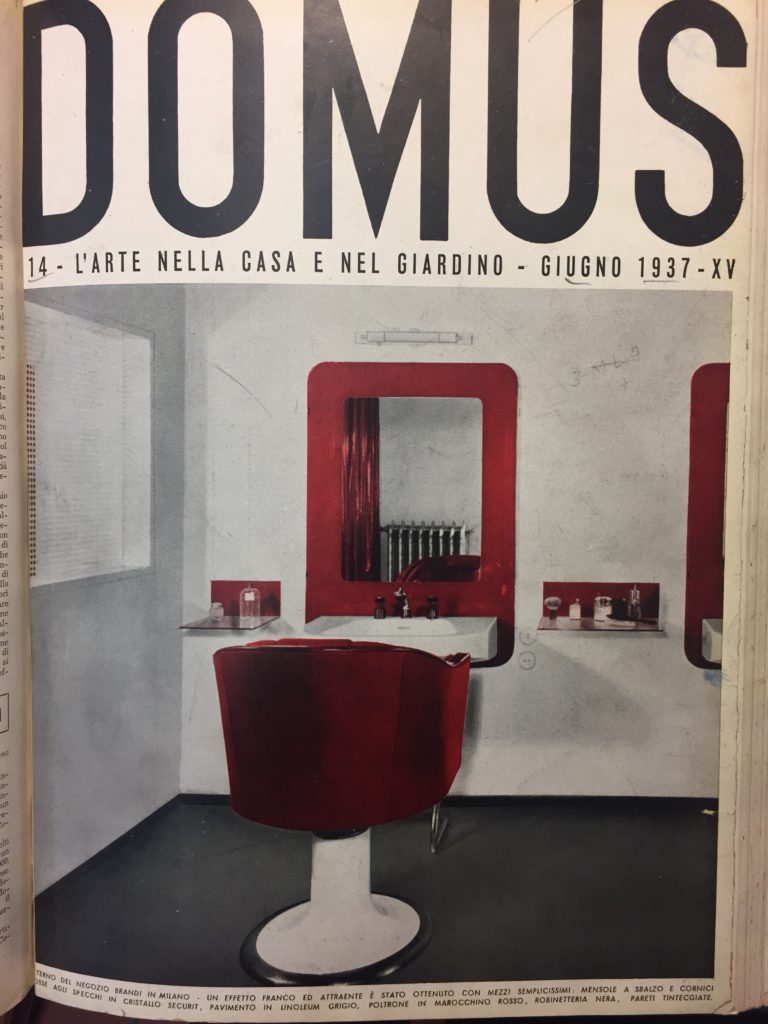

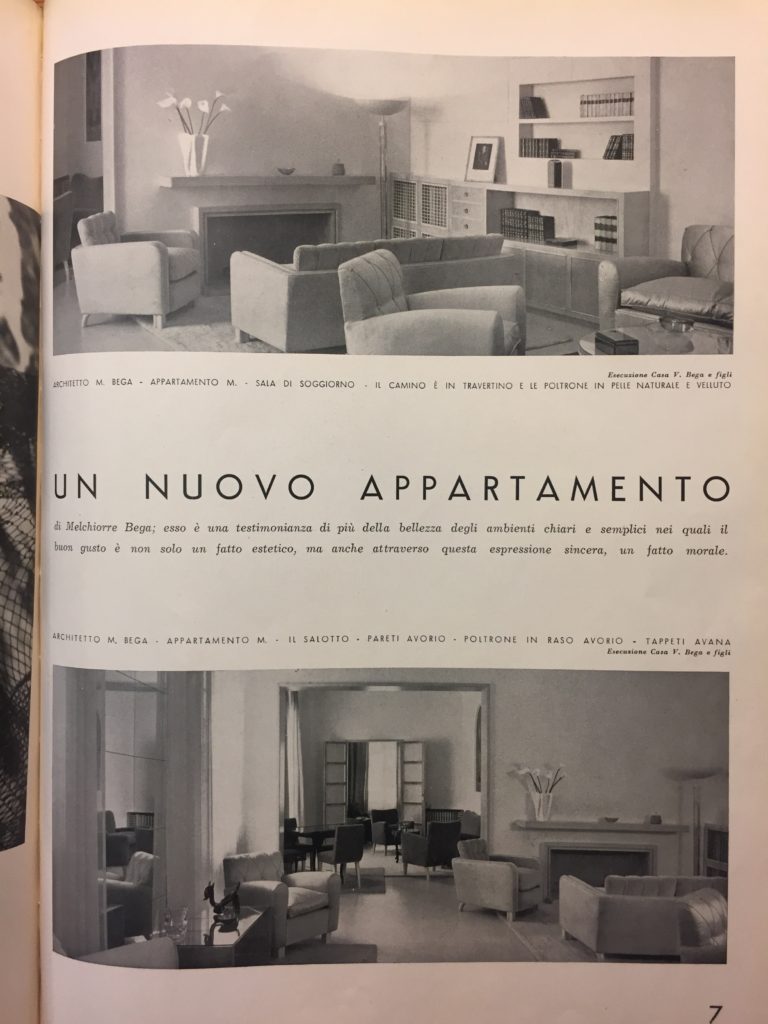

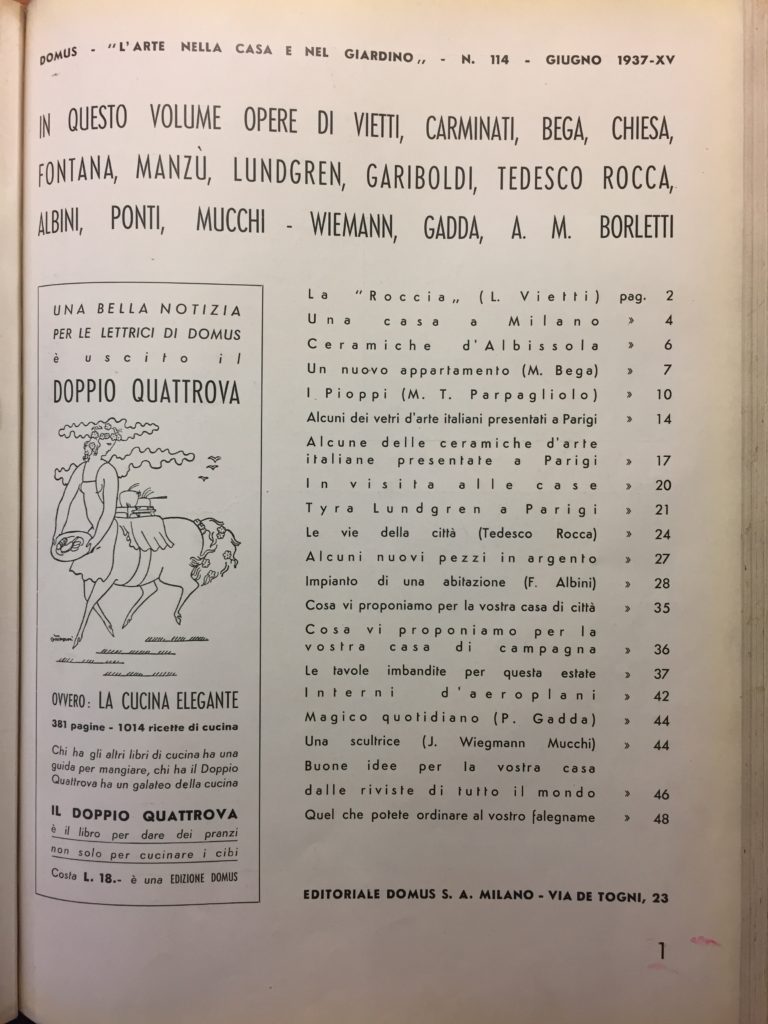

Ponti’s review appeared in Domus, the monthly magazine he’d founded in Milan in 1928. Though Domus’s stated editorial mission was “the art of the home and garden,” it covered a wide range of design issues, from home décor and interior decoration to urban planning, commercial architecture and use of public spaces. Under Ponti, Domus became a leading forum to debate the new trends in private and public architecture. Seeing in Bega a creative visionary, Ponti gave him space in the magazine. In a series of four articles in 1937, Bega laid out his principles of domestic interior design, using pictures of his private commissions along with his commentary. To many readers, the starkness was shocking. Bega had decluttered and de-ornamented living space, offering his trademark clean lines and volumes. For the more conservative defenders of bourgeois architecture and design, what Bega was proposing was scandalous.

It was only natural that in 1941, when Ponti stepped down as editor at Domus that he named Bega as his successor. Calling on the talents of Italy’s leading designers and critics, including Massimo Buontempelli, Giuseppe Pagano and Guglielmo Ulrich, Bega expanded Domus’s range even further to include sculpture and painting as essential elements in the creation of fully realized interior design. Bega’s direction changed the editorial team of Domus without upsetting its structure. He called on his artists and sculptors to contribute—these included Sironi, Carrà, Severini. Bega also extended the Ponti tradition of allowing Italy’s leading architects to use the pages of Domus as a creative laboratory, running articles and designer spreads from BBPR to Zanuso and Mollino among others.

With the end of World War II, the “Bega 2” phase of the designer’s career began, with a focus on the design of commercial and public buildings, first in concrete and later in steel.

“I always dreamt of building in steel, because steel for me has an emotional power. Steel is among the most suitable materials not only because it can address the main preoccupations of contemporary engineering – to create stronger and more daring structures – but because of its natural, inherent, fascinating elegance.

The first half of our century helped the maturing of a specific esthetic4supported by the figurative arts, a real ‘credo of the right angle’— an esthetic of the right angle as the foundation for architectural design. Steel, more than cement, is the material that was created to respond … to the esthetic rigors of the right angle.” 5

Towers by Bega

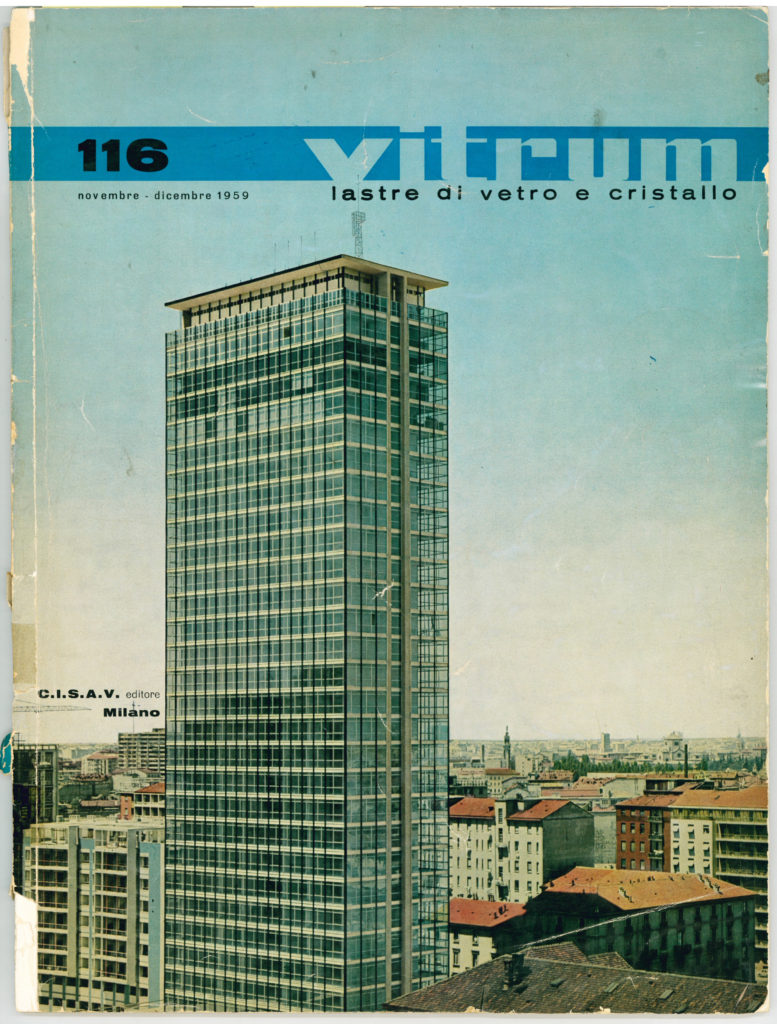

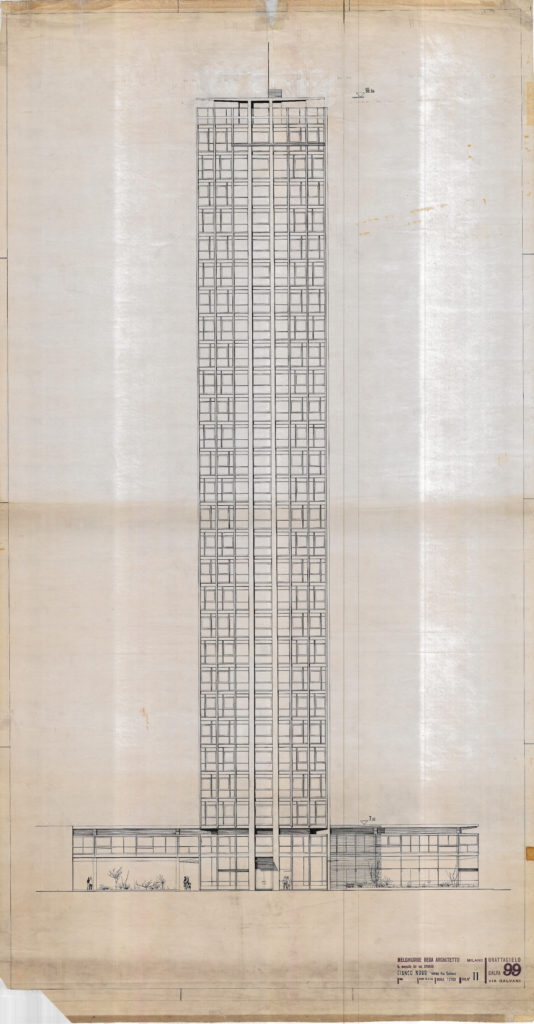

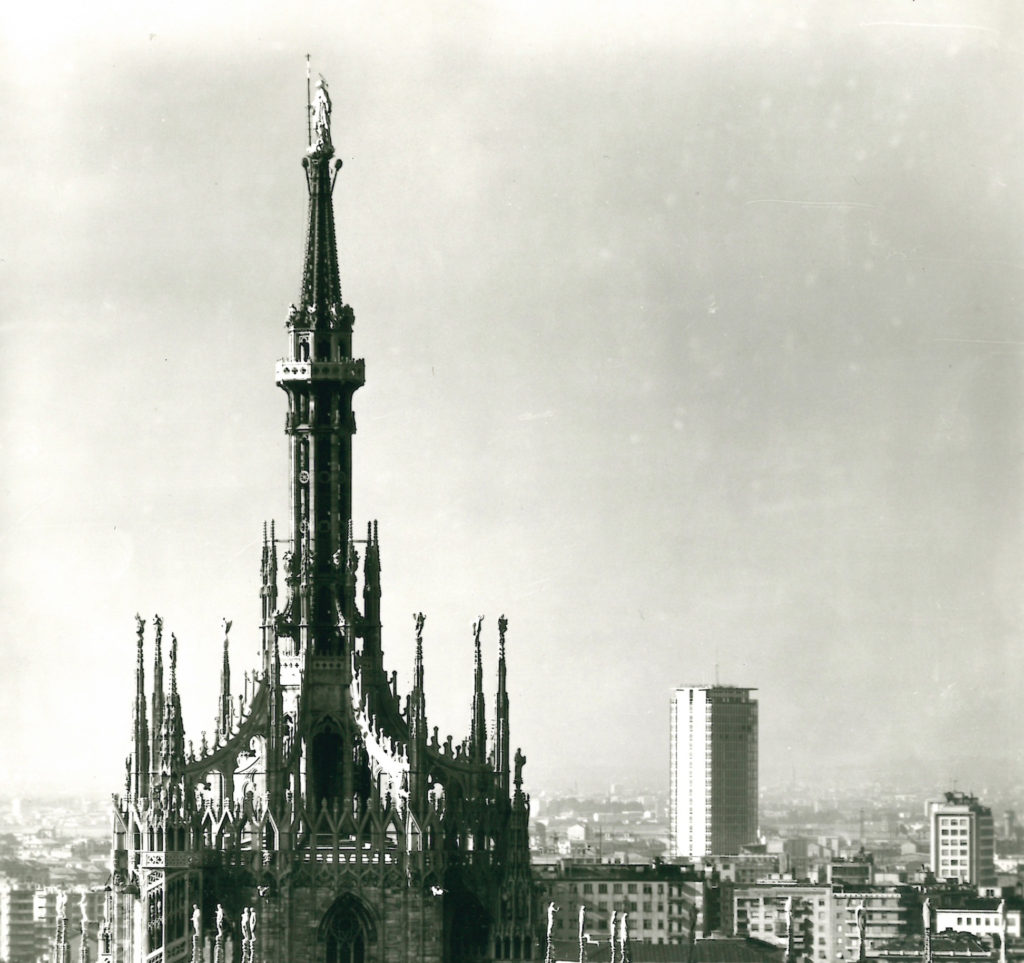

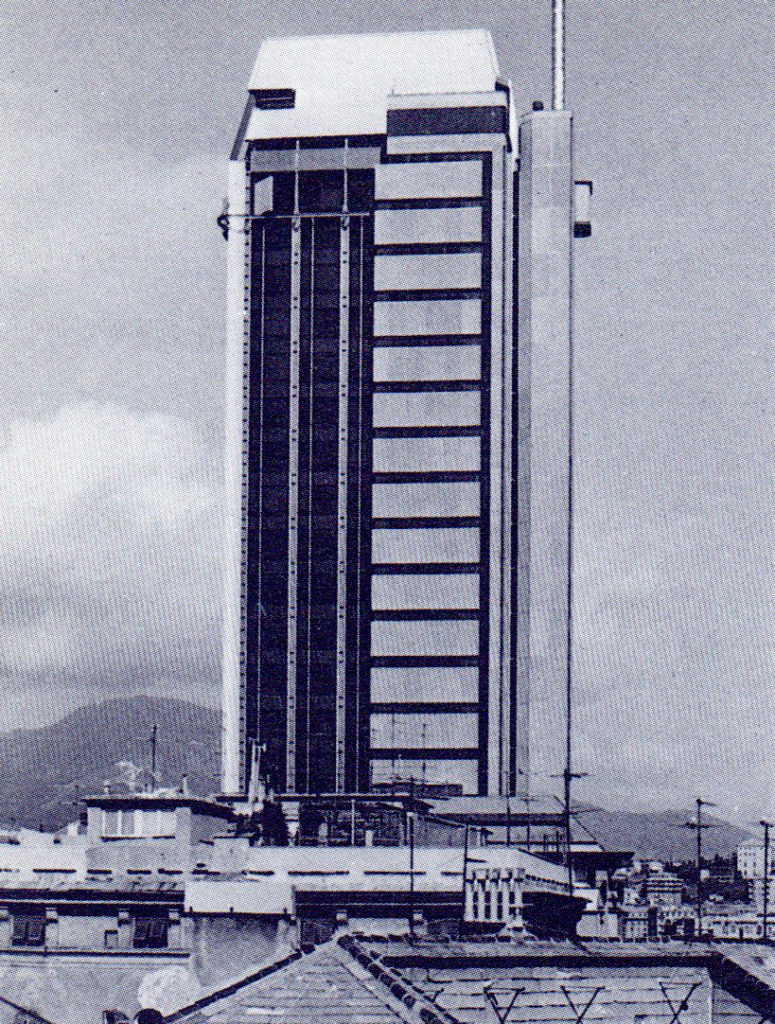

The most important architectural projects of Bega’s post-war career are the office towers he designed in Milan, Bologna, Genoa and Berlin. Foremost among them is the Galfa Tower, the 30-story skyscraper Bega conceived as the corporate headquarters for the Rimini Oil Refinery Corporation in Milan. From contract to ribbon cutting, it took nearly a decade, but it remains a landmark of modern urban building design.7

The completion of the building in 1959 established Bega as a true force in commercial building design in post-war Italy – and beyond. Reviewing it in Domus in 1961, Gio Ponti wrote:

“The Galfa skyscraper reaches a beauty that is immediately understood and loved because it embodies the shape of a technical, esthetic and representative truth. Bega’s tower is faultless in this context, which is in itself already a significant achievement: but one must add that because of the individuality of its structure, the perfection of its details, and the presence of a highly qualified architect who is expert in dealing with the requirements that our modern times impose on our wonderful profession, the Galfa tower reaches a particular level of architectural delight.” 6

Architecture critic Giuseppe Vaccaro characterized it as “the most chaste among Milanese high-rises; it does not want to flaunt its inventiveness or seek to surprise us.” 8

The commission came to Bega in May 1950 from Attilio Monti, founder of the Rimini Oil Refinery Corporation, who wanted a building for the company’s corporate headquarters. The name, Galfa, comes from its site at the intersection of avenues Galvani and Fara. It would be one of the jewels in Milan’s developing central business district, which was in the process of being established by Milan planning commission (Piano Regolatore).9

Monti convinced the Milan city planners to allow the building’s height to be increased from 80 meters to nearly 100 meters—30 stories—to match the neighboring Pirelli tower (designed by Gio Ponti), making it among the tallest buildings in Western Europe. Bega’s first design presented a steel structure but, as the technology was still relatively new in Italy, the design team opted for reinforced concrete. Joining Bega were structural engineers Luca Papini, Antonio Rognoni and Luigi Antonietti. Arturo Danusso, professor at the Milan Politecnico, came on board to do the structural calculations.

The Galfa Tower viewed close up

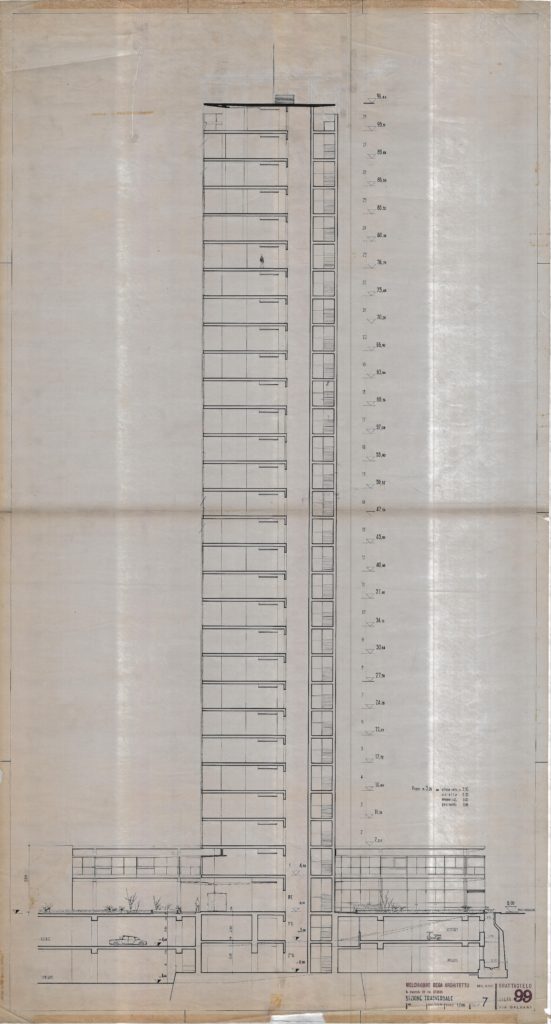

The Galfa Tower is built on a T-shaped plan, with a 102.5 m (336.3 ft) high center volume that extends for 31 floors above ground, with two 2-story 7.2 m (23.6 ft) side wings. Below ground level, two full floors are dedicated to mechanical, building services and parking.

The reinforced concrete structure is articulated into six load-bearing walls that are oriented at different angles, tapering as they ascend. Further support is provided by a system of load bearing interior walls that surround staircases and elevators.

Of the two exterior longitudinal fronts, one is completely glazed, while the other expresses the structural layout on the façade, covering it with gres-porcelain tile. The fully glazed eastern façade is characterized by the shifted plane of black mullions above the silver grid formed by the windows. The building corners are fully glazed, transparent and free of columns.

The two short fronts are also equal as well as contrasting: tiled surfaces alternate with window glazing, but the proportions of the two elements are complementary. The top two floors of the tower contain a variety of technical rooms and a double height panorama terrace, enclosed by full height glazing. At the very top, the exposed structural elements carry a thin reinforced concrete roof; it creates a sort of halo effect, detached from the floor below, where the mechanical equipment is located.

The building presents a very readable, uncomplicated plan, coupled with structural simplicity. Richard Neutra, a leader of midcentury architectural modernist design, praised its “architectural cleanliness.” Architectural historian and designer Leonardo Benevolo observed much Bega had advanced worldwide research on curtain walls with this building design. The tower’s partially cantilevered reinforced concrete structure, using a curtain wall solution, represents one of the first-use cases of this technology in Italy.

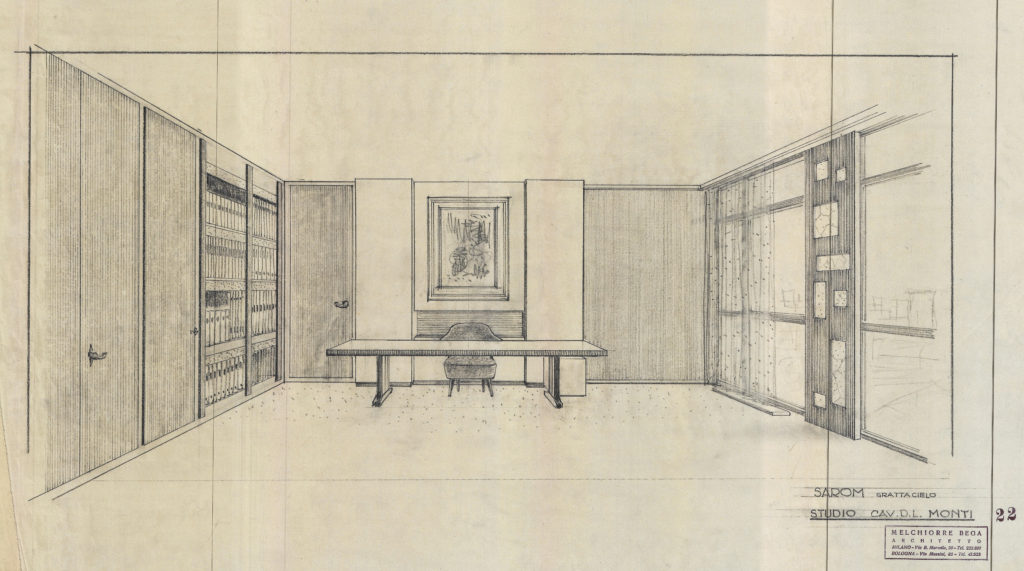

The interior space

Through careful design study of the façade’s modulation, Bega calibrated and composed a unitary interior and exterior, without any sign of rigidity: the façade “dresses” the building and allows a view of the interior spaces. Use of light as a design element emerges strongly. Bega was of the firm belief that penetrating daylight provided psychological comfort and maximum workplace efficiency. He wanted much taller single-pane window frames than those ultimately used. Unfortunately, due to the technical limitations at the time, the manufacturer was obliged to insert an additional horizontal element in the glazing, with the result we see today.

Galfa Tower’s interior and exterior architecture are fully coherent: spaces follow each other around the scene-setting pillars, avoiding annoying subdivision into segregated cells, and confirming the exterior volumetric clarity through internal spatial unity.

The building was completed in 1959 to great acclaim. Though not the tallest building in Milan at the time—the Pirelli and Velasca towers were slightly taller—for its timeless elegance and ingenious structural solutions, the Galfa Tower’s impact was far-reaching. Executives from the German publisher Axel Springer so admired it that they hired Bega to lead the design for their new headquarters in Berlin. Designed in collaboration with G. Franzi and T. Franzi and the local architects H. Sobotka and G. Muller, the Axel Springer project broke ground in May 1959. It was originally conceived as a 148-meter tower to be located on the eastern edge of the Berlin wall. Due to restrictions that limited building height in that area, the tower was revised to be an understated 19-story rectangular building, a classic of International Style. It was completed in 1966, with an external cladding composed of olive bronze anodized panels.

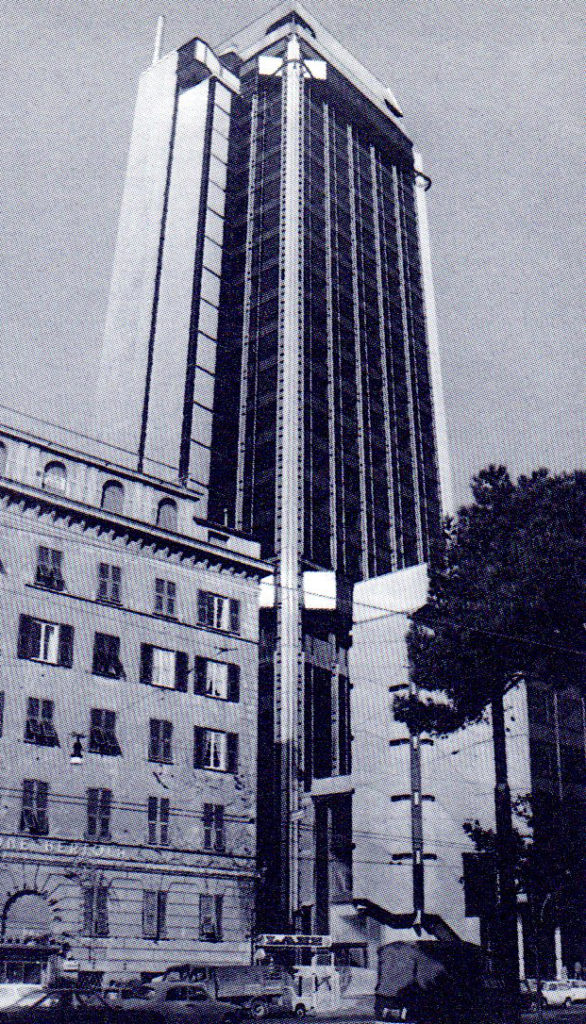

The third significant building in Bega’s post-WW2 legacy is the skyscraper he designed for the regional offices the Italian telephone company (SIP) in Genoa, completed in 1969. It was designed in collaboration with Piero Gambacciani and Attilio Viziano, with structural engineering by the firm Daldacci and systems provided by A. Altieri. Located in the Brignole section of town, the building, now known as the Torre San Vincenzo, is articulated in a 105-meter high steel and glass structure of 28 floors above ground and three below, and a separate reinforced concrete base of eight floors, of which six are above ground.

The tower section itself is set back from the base, creating a sense of space and setting it off from the surrounding buildings. Much as he loved right angles, Bega finished the top of the tower by cutting into the right angle to form a sort of hexagonal summit, further freeing up space around it.

Bega today

Though it is difficult to find examples of Bega’s interior design and furnishing from the 1920’s and 1930’s, his furniture is highly prized and fetches high prices. Most of the cafés and stores have succumbed to successive remodeling. His public buildings remain. Considered a modern classic, the Torre San Vincenzo in Genoa underwent a careful refurbishment in 2000 and is now home to the Italian trade association, Confindustria.

In 1980 Galfa Tower was sold to the bank Banca Popolare di Milano, which left the building in 2001 and sold it in 2006 to the current owner, the insurance group Fondiaria – SAI (today UnipolSai). The ongoing renovation project which started in January 2016 (designed by the architects BG&K Associati) will requalify Galfa Tower with mixed hospitality and residential use.

The Axel Springer company occupied its building in Berlin until last year when it moved to a new headquarters designed by Rem Koolhaas.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Melchiorre Bega Architect, Interior Architecture (Melchiorre Bega Architetto, Architetture d’interni), Editoriale Domus, 1931

Raffaello Giolli, The opus of Melchiorre Bega (L’opera di Melchiorre Bega), “Casabella”, n.119, November 1937

Melchiorre Bega Builder (Melchiorre Bega costruttore), “Domus” n.156, December 1940

Stefano Zironi, Melchiorre Bega Architect (Melchiorre Bega architetto). Editoriale Domus, Milan 1983

NOTES

1-Raffaello Giolli, L’opera di Melchiorre Bega (The Work of Melchiorre Bega), “Casabella”, n. 119, 1937, pp.6-9.

2- “His architecture certainly does not belong to nostalgic memories or tired revivals; he dedicated his entire life to architecture, with a way of life and thinking that has taken him from the beginnings of his career in his father’s firm to the creation of large and famous architectural works in his mature age. After the end of the war, a free man, he could participate in a fervid reconstruction, without compromises or impositions holding him back. Difficult not to be fascinated by such creative vivaciousness, not to comprehend the enthusiasm and the need for continuous research aimed at the creation of new experiences”.

C. G. Argan, Presentazione (Preface), in Stefano Zironi, Melchiorre Bega architetto, (Melchiorre Bega Architect) Editoriale Domus 1983, p 6-8.

3- A catalogue with an introduction by Gio Ponti is published as a testimony to his professional activity in the 1930s. “The completion of bars, stores like the Rimmel Valli perfumery, the Lana Innova manufacture, the renovation and furnishings of the Uddan theater in Tripoli (Libya), the interiors of clinics and hospitals or famous residences like the Royal Palace in Bolzano, all employ specifically chosen materials that were well suited and shaped by his artistic and stylistic will (…).

Gio Ponti, presentazione Architetture d’interni, (presentation Architecture of Interiors) Editoriale Domus, Milan, 1937-XV.

4- M .Bega interview, “Finsider”, year IX, no. 2, June 1974.

5- M. Bega in Raffaello Giolli, L’opera di Melchiorre Bega, (The Opus of Melchiorre Bega) “Casabella” 1937 n. 119.

6- Gio Ponti, Le torri di Milano: la torre Galfa,( The Towers of Milan:The Galfa Tower), Domus, year 1961, n. 377, p. 3.

7- For the research on the Galfa Tower project preceding its recent restoration, the heirs of Melchiorre Bega gave Alessandra Coppa access to the catalogued materials of their private archive. The available documents are kept at Studio Bega at via Benedetto Marcello 20 in Milan (the same office where Melchiorre practiced), are in good condition. They include: drawings and sketches in ink and pencil on both Mylar and regular paper, large scale blueprints with two different titleblocks: “Melchiorre Bega Architetto, via B. Marcello, 20 – Grattacielo Galfa 99 – Milano via Galvani” and “Studio Tecnico dott. Ing. Antonietti – Papini – Rognoni”; perspective view drawings of the interiors, construction details, approximately 150 documents in total; approximately 70 items of photographic material (plates, negatives and prints); handwritten notes and printed articles; original professional publications of the period; one architectural model.

8- Giuseppe Vaccaro, Il Grattacielo Galfa a Milano, (The Galfa Skyscraper in Milan), “L’Architettura”, n. 48, 1959.

9- The Galfa Tower has been built in accordance with the Reconstruction Plan (Piano di Ricostruzione) which was approved by decree of the Italian Ministry of Public Works on February 28, 1949 , n.322, confirmed by the Milan Master Plan (Piano Regolatore Generale) approved by decree of the President of the Italian Republic on May 30, 1953, and with the Executive Detail Plan (Piano Particolareggiato – executive instrument of the aforementioned Master Plan) which was approved April 9, 1956.

Author

Alessandra Coppa is an architect, journalist and publicist living in Milan. She has published monographs on Giuseppe Terragni, Mario Botta and Adolf Loos among others for Sole 24 Ore. Besides her writing activities she is teaching Contemporary Architectural History at the Milan Politecnico and created the Architecture and Design publication series for Corriere della Sera, Milan’s daily newspaper. Sam Perkins is a New York based writer and board member of SilentMasters. For his full bio please see here.